This is part of a series of articles by Greece Is on early travelers to Greece, including as much as possible the travelers’ own words recorded in diaries and letters.

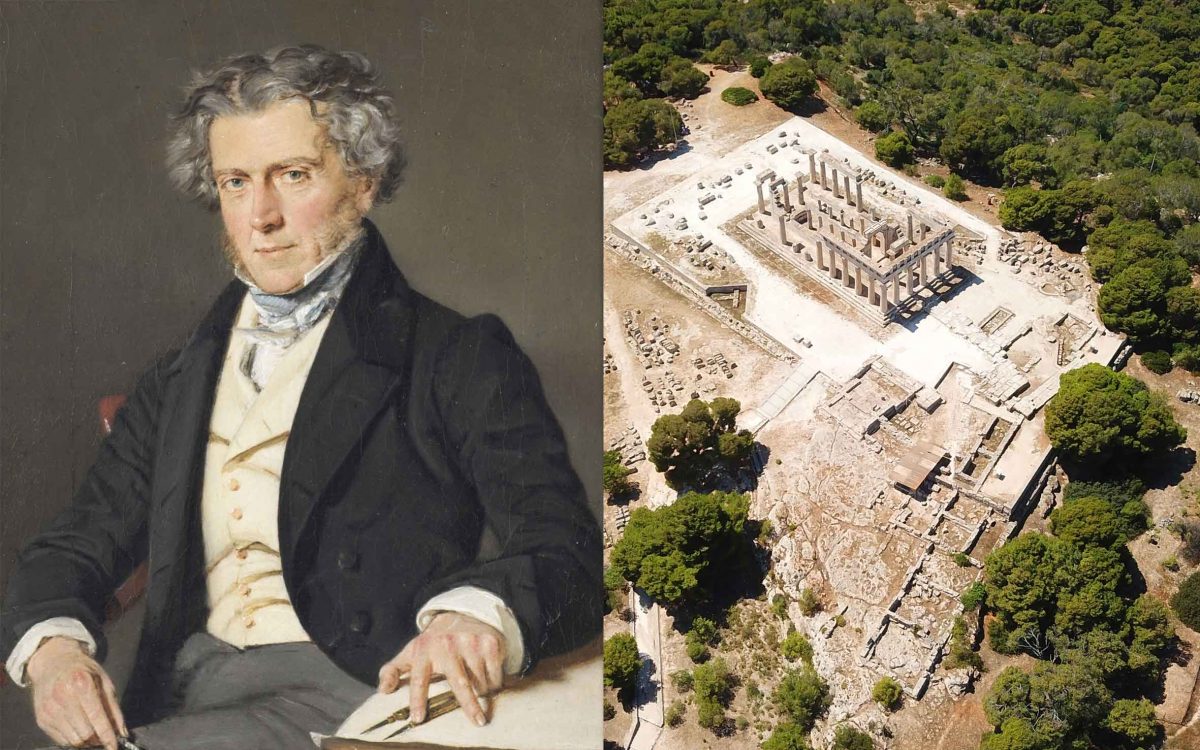

This is the second installment on Charles Cockerell, who visited Greece in the early years of the 19th century as a budding young English architect and antiquities plunderer. For part I click here.

Last episode: Cockerell travels to Constantinople and Salonika; has to deal with pirates and a mutiny; explores Delos; arrives in Athens; joins a circle of like-minded travelers; and departs for Aegina…, pausing for a tipple on the high seas with Lord Byron.

Episode 2: Unearthing Ancient Warriors

Panoramic Views & Nightly Feasting On arriving in Aegina, probably on 19 April 1811, with his friends Haller, Linckh and Foster, Cockerell writes:

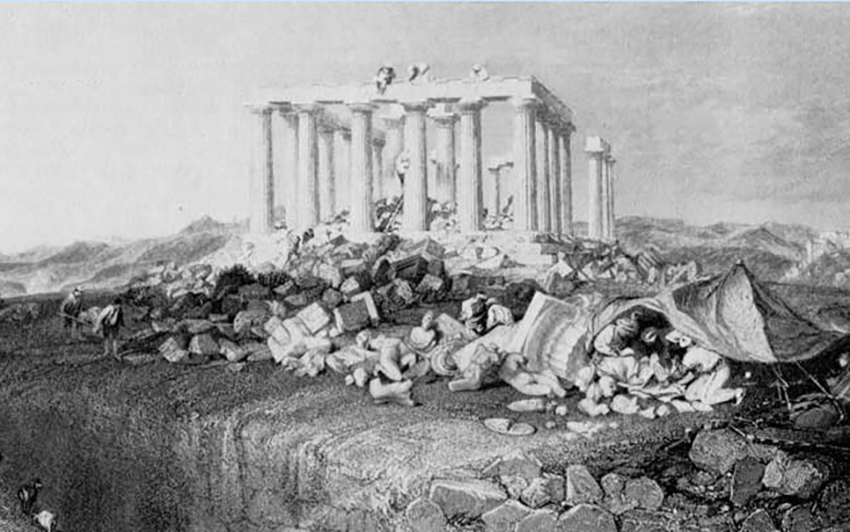

“The port is very picturesque. We went on at once from the town to the temple of Jupiter [Aphaia], which stands at some distance above it; and having got together workmen to help us in turning stones, etc, we pitched our tents for ourselves, and took possession of a cave at the northeast angle of the platform on which the temple stands – which had once been, perhaps, the cave of a sacred oracle – as a lodging for the servants and the janissary.”

“The seas hereabouts are still infested with pirates, as they always have been. One of the workmen pointed me out the pirate boats off Sunium, which is one of their favourite haunts, and which one can see from the temple platform. But they never molested us during the twenty days and nights we camped out there, for our party, with servants and janissary, was too strong to be meddled with.”

“We got our provisions and labourers from the town, our fuel was the wild thyme, there were abundance of partridges to eat, and we bought kids from the shepherds; and when work was over for the day, there was a grand roasting of them over a blazing fire with an accompaniment of native music, singing and dancing.”

Revelations Just Beside the Temple

“On the platform was growing a crop of barley, but on the actual ruins and fallen fragments of the temple itself no great amount of vegetable earth had collected, so that without very much labour we were able to find and examine all the stones necessary for a complete architectural analysis and restoration. At the end of a few days, we had learnt all we could wish to know of the construction, from the stylobate to the tiles, and had done all we came to do.”

“But, meanwhile, a startling incident had occurred, which wrought us all to the highest pitch of excitement. On the second day, one of the excavators, working in the interior portico, struck on a piece of Parian marble which, as the building itself is of stone, arrested his attention. It turned out to be the head of a helmeted warrior, perfect in every feature. It lay with the face turned upwards, and as the features came out by degrees, you can imagine nothing like the state of rapture and excitement to which we were wrought.

“Here was an altogether new interest, which set us to work with a will. Soon another head was turned up, then a leg and a foot, and finally, to make a long story short, we found under the fallen portions of the tympanum and the cornice of the eastern and western pediments no less than sixteen statues and thirteen heads, legs, arms, etc, all in the highest preservation, not 3 feet below the surface of the ground. It seems incredible, considering the number of travellers who have visited the temple, that they should have remained so long undisturbed.”

“It is evident that they were brought down, with the pediment on the top of them, by an earthquake, and all got broken in the fall; but we have found all the pieces and have now put together, as I say, sixteen entire figures.”

Troublesome Workers…

“The unusual bustle about the temple rapidly increased as the news of our operations spread… Greek workmen…can be uncommonly insolent when there is no janissary to keep them in order. Once, while Foster, being away at Athens, had taken the janissary with him, I had the greatest pother with them. A number that I did not want would hang about the diggings, now and then taking a hand themselves, but generally interfering with those who were laboring, and preventing any orderly and businesslike work. So, at last I had to speak to them.

“I said we only required ten men, who should each receive one piastre per day, and that was all I had to spend; if more than ten chose to work, no matter how many they might be, there would still be only the ten piastres to divide amongst them. They must settle amongst themselves what they would choose to do.

“Upon hearing this, what did the idlers do? One of them produced a fiddle; they settled into a ring and were preparing to dance. This was more than I could put up with. We should get no work done at all. So I…stopped it, declaring that only those who worked, and worked hard, should get paid anything whatever. This threat was made more efficacious by my evident anger, and gradually the superfluous men left us in peace, and we got to work again.”

…and Local Authorities

“It was not to be expected that we should be allowed to carry away what we had found without opposition. However much people may neglect their own possessions, as soon as they see them coveted by others they begin to value them. The primates of the island came to us in a body and read a statement made by the council…, in which they begged us to desist from our operations, for heaven only knew what misfortunes might not fall on the island…, and the immediately surrounding land in particular, if we continued them.

“Such a rubbishy pretense of superstitious fear, was obviously a mere excuse to extort money. As we felt it was only fair that we should pay, we sent our dragoman with them to the village to [negotiate] the sum. Meanwhile, a boat which we had ordered from Athens having arrived, we embarked the marbles without delay and sent them off under the care of Foster and Linckh, with the janissary, to the Piraeus, and from thence they were carried up to Athens by night to avoid exciting attention. Haller and I remained to carry on the digging, which we did with all possible vigour.

“The marbles being gone, the primates came to be easier to deal with. We completed our bargain with them to pay them 800 piastres for the antiquities we had found, with leave to continue the digging till we had explored the whole site. Altogether it took us sixteen days of very hard work, for besides watching and directing and generally managing the workmen, we had done a good deal of digging and handling of the marbles ourselves; all heads and specially delicate parts we were obliged to take out of the ground ourselves for fear of the workmen ruining them.

“On the whole, we have been very fortunate. Very few have been broken by carelessness. Besides all this, which was outside our own real business, we had been taking measurements and making careful drawings of every part and arrangement of the architecture till every detail of the construction and, as far as we could fathom it, of the art of the building itself was clearly understood by us.”

© Shutterstock

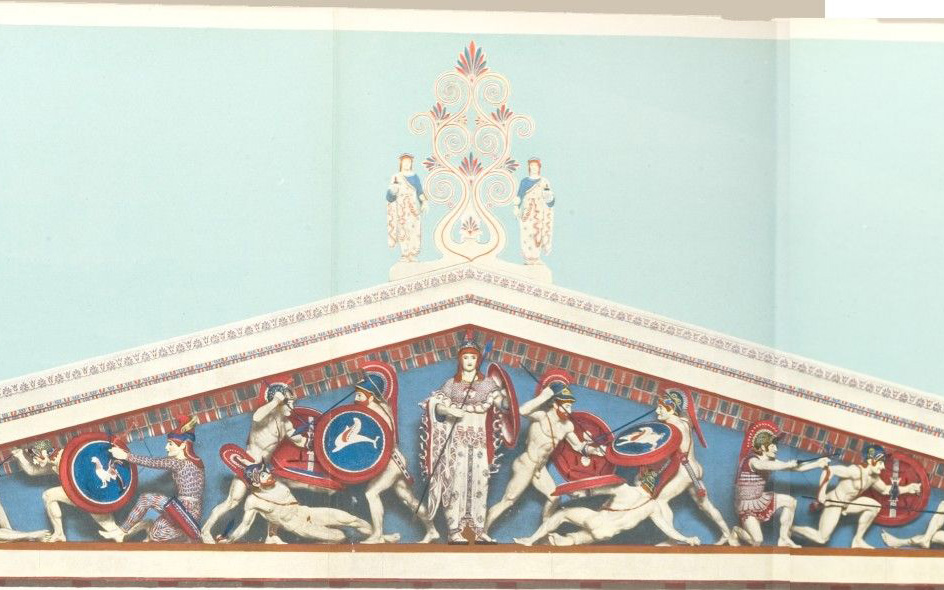

Magnificent Sculptures, the Envy of All

Cockerell and his party returned to Athens with their collected treasures on about 9 May 1811. In the following days, he recorded:

“We are now hard at work joining the broken pieces, and have taken a large house for the purpose. Some of the figures are already restored, and have a magnificent effect. Our council of artists here considers them as not inferior to the remains of the Parthenon… We conduct all our affairs with respect to them in the utmost secrecy, for fear the Turk should either reclaim them or put difficulties in the way of our exporting them.

“The few friends we have and consult are dying with jealousy… Fauvel, the French consul, was also a good deal disappointed; but he is too good a fellow to let envy affect his actions, and he has given excellent help and advice.

“The finding of such a treasure has tried every character concerned with it. [Fauvel] saw that this would be the case…and proposed our signing a contract of honour that no one should take any measures to sell or divide it without the consent of the other three parties. This was done. It is not to be divided. It is a collection which a king or great nobleman who had the arts of his country at heart should spare no effort to secure; for it would be a school of art as well as an ornament to any country.”

Excited by their Aigina trip’s successful outcome, the companions wrote to governmental contacts back home to inquire about their respective nations’ interests in the sculptural collection. Fauvel, as well, Cockerell reports, “will make an offer to us on the French account.”

Another touring Englishman then in Athens, Howe Peter Brown, 2nd Marquess of Sligo, similarly expressed an interest. Despite a reputation as a hopeless spendthrift, however, he declined to enter negotiations.

Cockerell laments that Haller and Linckh, having calculated the antiquities’ value by the price of marbles in Rome, “have named such a monstrous figure [6,000 – 8,000 Italian Napoleonic lira] that it has frightened him.”

Next episode: Cockerell and company tour the Peloponnese and discover more ancient treasure at Bassae; a conspiracy is devised to ensure Britain’s agent fails to show up at the auction of the Aigina marbles.