Thessaloniki’s Long-Awaited Transformation Takes Shape

From major infrastructure projects to a...

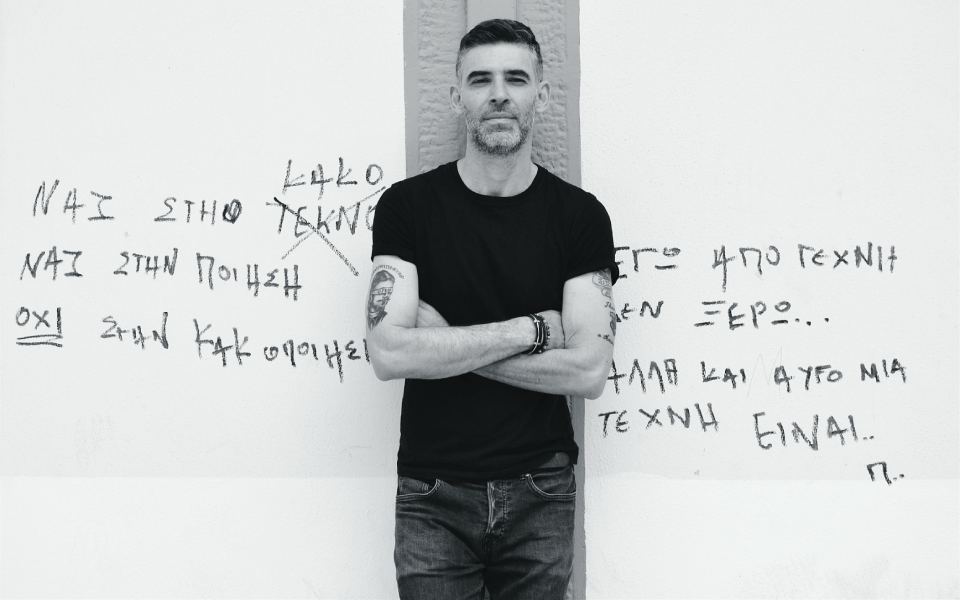

© Art work: Blaktoo

Anyone seeing him from a distance, say from a balcony across the way, might be concerned; every afternoon shortly before dusk, a young man would perch at the edge of the cement surface, standing motionless, staring out over the city, over the roofs of the houses and apartment buildings and up at the sky. “He’s just looking out at Thessaloniki,” a calmer person might reason – after all there isn’t any other way to do so these days.

And, in fact, that’s just what would do for a spell. He would listen to the metaphysical silence, observing the city, which seemed to be wrapped in an airtight plastic membrane. Before him loomed the Church of Saint Demetrius, while at his back stretched the cement forest of apartment buildings erected during the postwar building boom. To the left, was the domed roof of the Rotunda, while straight down was the White Tower, and then the sea and the stooped cranes at the port. To the rear was Vlatadon Monastery, the northern walls of the city and, in the distance, the yellow streetlights of the ring road, their light further accentuating the absence of vehicles: an entire world on mute, with countless lives on pause.

After a while, he would turn around and unlock the mesh door of the coop. He’d never thought that these pigeons would be his only contact with the outside world for weeks. His late father had saddled him with them. He had called him when it was clear that he didn’t have long left, beseeching him to take care of them. After his father’s death, he had wavered. After all, his father would never know, and he had no desire to return to that neighborhood, to that house, in the city’s wrinkled belly, between Saint Demetrius and Ano Poli. But, in the end, he didn’t have the heart to turn his back on one of his father’s last wishes.

And so he would head up to the roof of the building every day, and with whistles would coax them out, using a pole to send them high in the sky above Thessaloniki. Then he’d turn over a crate, sit down, and watch them, sometimes with a coffee, sometimes a beer. It wouldn’t be long before another pigeon, belonging to some other owner, would get mixed up with his. At first, he would lose track of it amid his own flock, but with time his eye became more practiced. He would then stand up, raising his hands toward the horizon and try to summon it. Under ordinary circumstances, he never would have done that. Before quarantine, that is; he would have considered it unethical. Instead, he’d have let the lost birds find their way back to their owners. But now he was always eager for it to happen and disappointed when it didn’t. And this because, one afternoon during the first week of the whole miserable affair, another pigeon keeper had hung on to one of his own pigeons for a bit, and then sent it back with a small note tied to its leg. “Today I became a grandfather,” it said.

In the suffocating solitude of those days, those unevenly scrawled little words cut him to the quick, but they gave him strength, too. Life was continuing out there, in spite of the circumstances, and it seemed clear that humankind would always find a way to share its sadnesses and its joys. That’s how it started, or perhaps it had started even earlier, only he hadn’t been taking part, but every evening the pigeon keepers in that part of the city would exchange messages, indiscriminately and continually, in an open conversation of hope and perseverance:

“As soon as this is all over, I’m buying everyone a round at De Facto.”

“There’s an amazing movie at nine on Channel One tonight.”

“Tsirogianni Plaza is the most beautiful square in the whole city.”

“I met my wife at Igglis thirty years ago.”

“Did anyone else see the colors of the sunset over the Thermaic Gulf today?”

“When we get out of this, I’m going to head straight to my favorite bar in Saranta Ekklisies.”

“There’s a place on Kassandrou Street that makes the most amazing custard pies.”

“With your father, we would watch every single PAOK match, every weekend.”

“My granddaughter is a month old and I still haven’t seen her.”

“What I miss most is going for walks along the eastern walls of the city, from Aghios Pavlos to the White Tower.”

“From what I hear, our hour of freedom is approaching.”

“I never came up here, not even once, with my father.

I always declined his invitations.”

“My son got sick yesterday. I didn’t sleep a wink all night.”

“It’s the last few days of this, friends. Keep your heads up.”

“Did you go to the 3rd High School, too? The school where Yorgos Ioannou and Antonis Sourounis went?”

“On Tuesday everybody meet in front of the Longos Mansion. The time has come.”

They all spilled out into the streets, as if returning from a battle that was over, but which they were not sure they had won. Happy, but not carefree. Everything was the same, but also different. The sun was bright but no one wanted to put on their sunglasses. The neighborhood shops finally pulled up their security grills and unlocked their doors, and people who’d walked straight past one another for years started to exchange conspiratorial greetings. The color red made people think of fire rather than blood, whispers of relief were sincere, and the city was suddenly alive again, beating like a sprinter’s heart. None of them missed the meeting they’d arranged; they all crossed the city by foot, heading down from Raktivan Street, from Aghia Sofia, Ioulianou, Antigonidon (which isn’t called Antigonidon anymore except by people of a certain age), and every so often they’d look up at the sky, mostly out of habit, with the thought that they might see some friend of theirs wheeling through the clouds, one of those silent messengers that, for a time, had been transformed into carriers of dreams and of freedom, the pigeons of Saint Demetrius.

Keeping pigeons has been a tradition in Thessaloniki since before WWII and the German occupation. In fact, until the city’s skyline became dominated by apartment buildings in the 1960s, dovecotes were common sights in backyard gardens. Today, the city’s pigeon fanciers tend to their flocks almost exclusively on rooftops, using Wuta, Donek and carrier pigeons, while the practice of attempting to lure birds from other flocks into one’s own during flights is common.

KYRIAKOS GIALENIOS was born in Thessaloniki in 1978. His debut novel “The Lovers’ Disease” was shortlisted for the Young Writer’s Award from the Michael Cacoyiannis Foundation in 2011 and the State Literary Award For First-Time Authors in 2012. He has also authored “Only Dead Fish Follow the Current,” published in 2015.

From major infrastructure projects to a...

This short walk takes in eleven...

Where dusk, movement, and memory meet,...

Landmark shops, a lively cultural scene...