Santorini Beyond the Crowds: What to See and...

Discover hidden beaches, authentic tavernas, ancient...

The photographer’s children – from left to right, Zander (the author of this article), Simon and Max Abranowicz – in Oia in the 1990s, during one of the family’s annual holidays to Greece.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

In the home videos of my first trip to Santorini, I’m a naked baby bathed in late-day sun, grasping at the black sand of a secluded beach, or giddy as I’m buoyed on the generous bosom of a Greek woman in the kitchen of a taverna while she coos beneath a canopy of bare bulbs. It was September of 1992 when my parents carried me, a babe of five months, off a small Olympic Air plane onto the tarmac at the then dinky Santorini Airport, exposing my skin to the famed Mediterranean light for the first time.

There to meet his godson was Kostis Psychas, owner of the Perivolas hotel and my father’s best friend. His beard was darker then, but his surfer’s sun-bleached hair and stunningly blue eyes have lost little of their luster today, twenty-six years later. My father first met Kostis in 1988, and over the years, on countless family trips and as a photographer for many magazines, he documented the stewardship Kostis and his sister Maria Irini exercised over Perivolas, whose traditional rock-hewn white houses first welcomed travelers in 1974.

The Aegean Sea serves as the backdrop to my boyhood memories of our annual visits to Kostis and Santorini. We are skimming on the caldera past cliffs of pocked igneous rock on Kostis’ beloved Zodiac, the nimble, inflatable boat often associated with Navy SEALs. We laugh and scream each time our bottoms are lifted from the floor of the boat as Kostis – the epitome of a waterman, whose closest physical correlates would be surfer Laird Hamilton or Disney’s Poseidon – propels the vessel off the surf.

My father photographs our summer entourage, tanned and windswept. Reflected light from the sea dances on the magma, settled millions of years ago into the perforated inner walls of the caldera. We disembark at Armeni, a small fishing village at the bottom of the cliffs below Oia, accessible by sea or by a hidden donkey path, and order fresh fried eggs, calamari, and Epsa lemon sodas that come in glass bottles. Kostis, whom we call “The Mayor of Santorini,” makes the rounds among the locals. On the surrounding tabletops sit quintessential elements of a Greek still life – cigarettes, cell phones, worry beads, frappés, glasses of water.

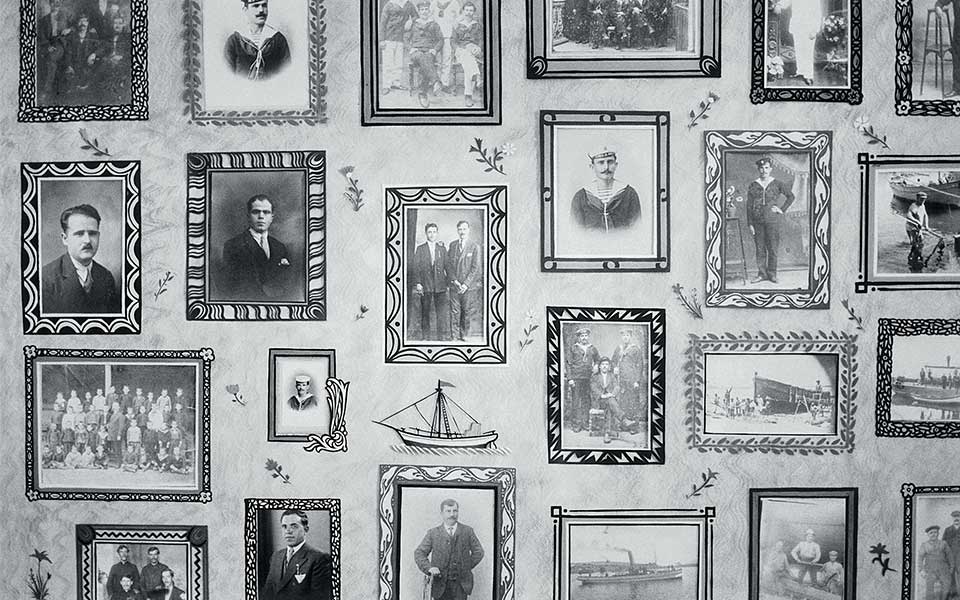

A wall of portraits at the Naval Maritime Museum in Oia, Santorini.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

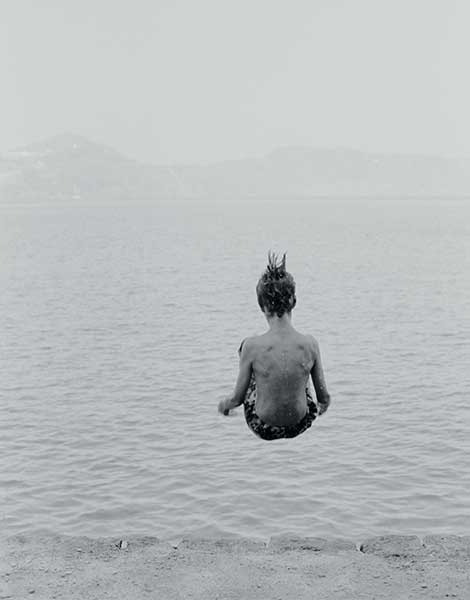

On our way back to the port of Ammoudi, somewhere between Thirasia and Santorini – the largest landmasses that encircle the caldera, like cupped hands – Kostis cuts the engine and the boat slows to stillness. Thousands of feet below us runs a volcanic fracture, the speculative site of the lost city of Atlantis. Wordlessly, he dives in. I follow. Beneath the water, my eyes track prismatic beams of sunlight to their terminal points below my treading feet.

The depths below me are immense – these are the coordinates where cruise ships make their turns to enter Santorini’s submerged crater on their way to the port. I’m swept with the nervous sensation of being exposed to whatever might emerge from those depths, and work to master my breathing. From the corner of my eye I see my godfather peacefully swimming well below me, occasionally pinching his nose to relieve pressure. My nerves give way to exhilaration and awe.

Children under 16 aren’t allowed at Perivolas, so visits to the hotel required our best behavior so as not to disturb the honeymooners relaxing at the edge of the famous infinity pool, or disrupt the reading and sunbathing of Greek celebrities on their balconies. My younger brother and sister and I would wade into the pool and paddle quietly around, lingering with our arms resting on the edge and peering down the cliffs below, where yellow-legged gulls and alpine swifts build gravity-defying nests amid the thorny scrub.

Kostis Psychas, owner of the Perivolas hotel as well as William’s close friend and Zander’s godfather, getting a trim at his home in Oia, Santorini.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

Once or twice each trip, Kostis would invite me to swim at the hotel by myself. I had to creep down from our hotel adjacent to Perivolas so as not to arouse the jealousy of my younger siblings. I’d swim, drink chocolate milkshakes at the hotel bar with Kostis’ daughter, Sandrine, two years my senior, then wrap myself in Perivolas’s luxurious grey and white towels – the same towels I’ve worn to a thread after years of use back home.

At eighteen, I found myself in Santorini without my family for the first time, a recent high school graduate disembarking a Hellenic Seaways ferry from Naxos with a half-way beard, a red bandana, a big hiker’s backpack, in the company of Conor, my oldest friend, from Bedford, New York. I spotted Kostis standing in front of his off-white, exquisitely gutted ’88 Range Rover, scanning the crowd, his azure eyes passing over me once, twice. It wasn’t until I was right in front of him that his eyes lit up – “You look just like you should!” he said, taking my backpack.

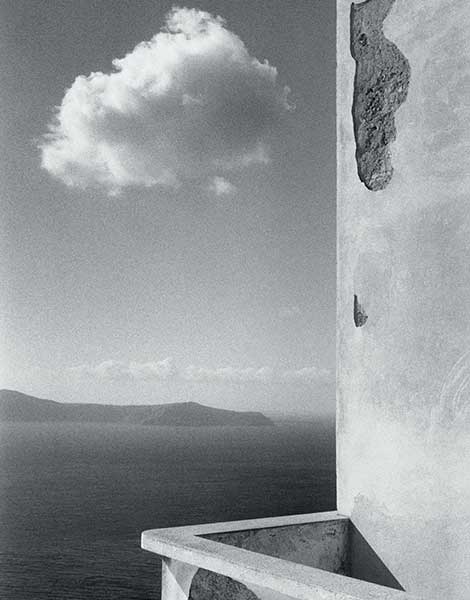

William’s iconic photograph of a cloud over the caldera was taken in Fira, Santorini in the 1990s. The austere site where he stood has since been turned into a lively café.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

Simon Abranowicz plunging into Santorini’s submerged caldera from Perivolas Hideaway, the hotel’s private residence on the island of Thirasia.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

Conor and I spent our days reading Henry Miller by the pool at Perivolas or cliff-jumping off the small island near Ammoudi, reveling in our freedom and speculating on what college had in store for us. That summer, Kostis was busy with the construction of his new home in the foundation of a 19th-century gypsum factory across the caldera on Thirasia; it was a light-colored structure on the shore barely visible from Perivolas.

Conor and I helped with the Sisyphean task of clearing rocks from the seawater pool, and swam around diving for sea urchin shells while Kostis led his team of laborers to create what was to become Perivolas Hideaway, a magnificent private house accessible only by helicopter or boat. On the Zodiac back to Santorini, Kostis, his expression visibly lighter when on the water, pointed the boat toward a cruise-liner’s wake. We momentarily left the water’s surface, like the dolphins or the flying fish depicted in late Minoan frescoes.

Linens drying on the line in Santorini in the 1990s.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

My vision of Greece as an idyllic playground of family travel changed as photos of an Athens aflame began appearing on the front page of The New York Times from 2008 onward. These photographs deeply troubled me, far away at university in Ithaca, NY, and inspired my research into the modern history of a nation I felt somehow had become my own.

Endowed with a generous grant to fund more than three months of field research, I let the rugged topography of the Greek spirit take form in my consciousness. I arrived in Santorini after months of traveling by foot, train, boat, and thumb, conducting interviews with activists, students, artists, journalists and politicians in Athens, farmers outside of Thessaloniki, survivors of the Axis occupation and Civil War in the borderlands of Epirus, and hermetic monks on the holy mountain of Athos.

Seeing before him a scruffy nomadic scholar beginning to resemble the ascetic saints depicted in Greek orthodox iconography, with worn-out shoes and dog-eared books by Patrick Leigh Fermor, Kostis gave me a crisp white Perivolas polo shirt, the kind worn by his staff, and a beautiful room at the hotel. Some of the faces and places associated with my youth – among them Pero, the toothless old man with a fisherman’s hat, rope belt, and stubble whom my father befriended as a young man, as well as the cantina where we would eat ham and cheese on toast after hikes up to a small white monastery – have disappeared. Behind me, too, are the trips from Athens to Santorini in the cockpit of miniscule Dornier 228 planes, arranged by Kostis’ brother Valodia, a man who’s as much a bird as Kostis is a fish.

The late Evgenios Spatharis was Greece’s foremost performer of Karagiozis plays, or shadow-puppet theater. His visit to Santorini in the 1990s was a momentous occasion for the island’s youth, including the Abranowicz kids and Kostis’s daughter, Sandrine, visible in the crowd.

© William Abranowicz/Art+Commerce

The drive in Kostis’ old Range Rover from the airport to Perivolas encountered more traffic than it ever had when I was young, with endless shabby hotels lining the route, and more under construction. Today, you’re more likely to find the road blocked by confused tourists on rented ATVs than by a shepherd and his goats. (Amid the economic crisis, Santorini increased its quota on cruise-ship arrivals, resulting in an exponential increase in tourists disembarking on the relatively small island. Thankfully, this policy was reversed in 2017.)

Santorini has taken form over two million years of successive volcanic eruptions, each depositing ash and magma and pumice into stratified layers of compressed earth. Small new islands such as Palea Kameni have appeared, and others have sunk back into the caldera. The homogenous infrastructure of modern tourism is simply the most recent residue of physical change on Santorini, unsightly as it is. The secluded wonder of the island hasn’t disappeared; out on the Aegean or within Perivolas’ sanctuary, my beloved secret remains preserved.

Discover hidden beaches, authentic tavernas, ancient...

Unspoiled beaches, authentic flavors, and a...

Where dusk, movement, and memory meet,...

Join expert guides and trained truffle...