The campaign for the return of the 2,500-year-old Parthenon Sculptures, also known as the “Elgin Marbles” in the United Kingdom, is the world’s longest-running cultural restitution dispute. The controversy revolves around the removal of dozens of decorative marble sculptures from the Parthenon in the early 19th century by Scottish diplomat Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin and British ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, when Greece was still under Ottoman rule. About half of the 160-meter-long frieze that originally adorned the 5th-century BC temple dedicated to the goddess Athena, along with 15 sculpted relief panels (metopes) and figures from the two pediments, were stripped from the monument and shipped to England. They were later acquired by the British Museum in 1816, where they have remained ever since.

Advocates for their repatriation argue that the sculptures are integral to Greece’s cultural heritage and should be reunited with the remaining fragments in Athens, now on display at the state-of-the-art Acropolis Museum, within direct view of the Parthenon. Many contend that removing the sculptures in the first place was both unethical and illegal – no official license (“firman”) signed by the Ottoman grand vizier has ever been recovered – and are therefore stolen cultural property that rightfully belongs to Greece. Others emphasize the importance of returning them to their historical and cultural context; the division of the sculptures between two museums is a fragmentation of the Parthenon monument, the crowning glory of Athens’ Golden Age.

Talking to the BBC during his brief, albeit eventful, visit to the UK in November, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis put it succinctly: “It’s as if I told you that you cut the Mona Lisa in half, you would have half of it at the Louvre and half at the British Museum, do you think your viewers would appreciate the beauty of the painting? This is essentially what happened with the Parthenon Sculptures.”

The growing trend for restitution

For 40 years now, the Greek government, cultural institutions, and a growing multitude of international supporters have engaged in various efforts to persuade the trustees of the British Museum to repatriate the sculptures. From the outset of the campaign, launched in 1983 by the indomitable Melina Mercouri (1920-1994), advocates have employed diplomatic channels, legal arguments and highly effective public awareness initiatives to garner support for the cause. The good news is that their efforts appear to be working. The past year has seen several significant developments in this decades-long dispute. According to the latest YouGov survey conducted in July 2023, 64 percent of Britons favor sending the sculptures back to Greece, up from 59 percent two years ago.

Proponents also point to the broader trend of repatriation in the museum world, emphasizing the importance of ethical considerations and respect for the rights of nations to their cultural heritage. But here’s where we come up against a serious problem. Those on the side of retaining the Parthenon Sculptures in London express concern that repatriation could set a dangerous precedent and impact other museums and collections worldwide. Western museums would essentially be emptied of their exhibits.

Frustrating matters even further, successive UK governments have refused to get involved in the specific case of the sculptures, always deferring it back to the trustees of the British Museum. Other European governments have been announcing new and updated restitution policies in recent years and giving cultural objects back to former colonial possessions, but the trustees of the British Museum appear stubbornly out of step.

© Paris Tavitian / Acropolis Museum

Where there’s a will, there’s a way

One of the most significant sticking points is the British Museum Act of 1963, which prevents the museum from returning items in its collection. And while the current UK prime minister, Rishi Sunak, has no plans to change the law to allow a permanent return of the sculptures to Greece, regional museums across the country, from Glasgow to Cambridge, have been returning hundreds of cultural artifacts from their own collections to indigenous peoples around the world, including, most recently, 174 sacred and ceremonial objects from the Manchester Museum to the Aboriginal Anindilyakwa community of the Gulf of Carpentaria, off the northern coast of Australia.

Speaking to the Guardian newspaper in September this year, Lewis McNaught, who runs the not-for-profit Returning Heritage project, said: “Regional museums are so far ahead of national institutions … it really just remains for national collections to wake up to the trend which is, actually, now global.” In the same article, Dan Hicks, a professor of contemporary archaeology at Oxford University as well as curator at the city’s Pitt Rivers Museum, said the whole debate around repatriation has become part of the “fake culture wars” with some on the political right seeing it as “wokery.”

“What that means, sadly, for our national institutions is that they are being forced into a position of inertia and making themselves increasingly irrelevant with every week that goes by and every restitution that we see from the regions and elsewhere around the world. Everyone else is getting on with it.” The good news is that fragments of the Parthenon Sculptures held in other European collections have been trickling back to Greece over the past two years. Among these have been the “Fagan fragment,” a piece depicting the foot of the goddess Artemis from the East Frieze, returned from the Antonio Salinas Museum in Palermo, Sicily, in 2022, and three fragments kept by the Vatican Museums in early 2023. Like regional museums across the UK and other parts of Europe, the Vatican has also voiced its willingness to return indigenous artifacts held in its collections. “The seventh commandment comes to mind: If you steal something, you have to give it back,” Pope Francis told the Associated Press in April. It seems that where there’s a will, there’s a way.

© AFP / VISUALHELLAS.GR

Hybrid deal: A “win-win” solution?

But is the British Museum really that behind the times? Towards the end of 2022, Greek newspaper Ta Nea revealed that the current chair of the museum, George Osborne, a former politician who served as Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016, had been holding secret “behind-the-scenes meetings” with the Greek prime minister regarding the fate of the sculptures. As soon as the news broke, the British Museum announced to the BBC that the talks were “ongoing and constructive.” In February 2023, Osborne used the phrase “win-win” when speaking about a possible “cooperative arrangement” with the Greeks, signaling a tectonic shift in resolving the long-running dispute. Suddenly, there was genuine optimism in the air.

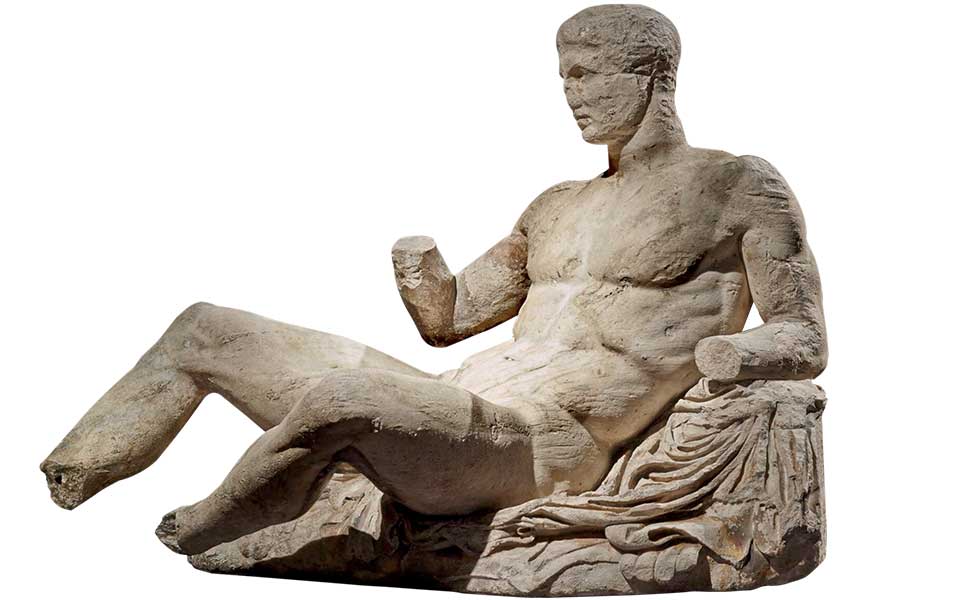

At the same time, the newly formed Parthenon Project, led by Lord Vaizey, a Conservative peer, began advocating for a specially tailored “cultural partnership agreement” between the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum in Athens, calling for both institutions to put aside the thorny issue of ownership and engage in a collaborative endeavor that would allow for the sculptures to be loaned back to Greece in return for “blockbuster artifacts that have never been seen outside Greece before.” The proposed “artifact swap” would include such items as the 3,600-year-old golden death mask of Agamemnon and the early 5th-century BC marble statue Kritios Boy. Importantly, this agreement would be deliverable within the current legal framework of the British Museum Act, thus overcoming a major stumbling block.

© The Trustees of the British Museum

The mutually beneficial partnership would also lay the groundwork for establishing a joint Greek-British Foundation that would “fund a long-term program of scholarships and wider educational and cultural activities to benefit young people in the UK and Greece,” according to the Parthenon Project website. Sources at the Parthenon Project recently told Kathimerini newspaper that it would also fund the new wing of the National Archaeological Museum in Athens.

Osborne believes an agreement for cultural exchanges between Greece and the British Museum would be a pragmatic compromise. Speaking at the annual dinner for the trustees of the museum in November, he called for an arrangement that would allow the sculptures to be seen in Athens and London but which “requires no one to relinquish their claims, asks for no changes to laws which are not ours to write, but which finds a practical, pragmatic and rational way forward.”

© Reuters

What Osborne is describing here is a “hybrid deal,” one that would respect the red lines laid down by both sides regarding the sticky issue of ownership. Nevertheless, it is important to stress that the Greek government would never agree to a loan of the sculptures, as this would concede British ownership. Under Greek law, all antiquities belong to the state, and past negotiations on this issue have quickly broken down, with the Greek culture minister, Lina Mendoni, describing Elgin’s removal of the sculptures in the early 19th century as “a blatant act of serial theft.”

For its part, the world governing body on the protection of cultural heritage, UNESCO, continues to push for a resolution. Τhe great success came on September 29, 2021, at the 22nd session of the Intergovernmental Committee of UNESCO for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property to its Countries of Origin. For the first time in 37 years of continuous propositions of the Committee towards the UK, a decision was made which, in addition to the legal and ethical aspects of the Greek request, also recognizes its transnational/intergovernmental character. The Committee also referred to the appalling conditions where the sculptures are kept in the 370-year-old museum, following news reports of water leaks and mold in the Duveen Gallery.

© Shutterstock

The King’s Speech

Considering all the progress that has been made in the past year, including the uptick in popular support in the UK for the return of the sculptures to Greece, the abrupt cancellation by the British Prime Minister Rishi Sunak of a planned meeting at the end of November with his Greek counterpart, Kyriakos Mitsotakis, has left people on both sides of the debate dazed and confused. “I am baffled, as are most people,” a leading member of the British Museum’s Board of Trustees told Kathimerini a day after the diplomatic snub.

In response, Mitsotakis called Sunak’s decision to cancel the meeting at the last minute “unprecedented” and “disrespectful.” And while Downing Street accused Mitsotakis of using the trip “as a public platform to re-litigate long-settled matters,” the row, momentarily at least, threatened to rupture the otherwise outstanding diplomatic relations between the two countries. But how has it affected the ongoing discussions regarding the fate of sculptures?

As the dust settles, it appears that Sunak’s grandstanding over the Parthenon Sculptures has backfired spectacularly, giving much-needed publicity to the campaign at a time when so many other, more pressing geopolitical events are competing for attention. Osborne, too, speaking to The Guardian at the end of November, revealed that Sunak had opened the door to a “devastating line of attack” from the opposition Labor Party and that he was more determined than ever to continue with “secret talks” with the Greek government over a deal.

© Chris Jackson / Getty Images / Ideal Image

© Shutterstock

In the same week, King Charles III, Britain’s staunchly Hellenophile head of state, quite literally nailed his colors to the flag at the COP28 climate summit in Dubai, donning a tie and breast handkerchief emblazoned with the blue and white Greek flag. This brazen show of support is not surprising. During his last visit to the country of his father’s birth in March 2021, for the bicentenary of the start of the Greek Revolution, the then Prince of Wales expressed a “profound connection” to all things Hellenic.

It is important to stress, however, that the trustees of the British Museum, as well as a growing majority of the UK public, are painfully aware of the fact that, of the eight million or so artifacts in the London-based museum, many were acquired through the aggressive expansion of its former empire. Nonetheless, this should not prove insurmountable, as long as there remains an appetite in Britain, and Europe more broadly, for an open debate about the enduring legacies of colonialism and imperialism and how we, as progressive, democratic societies, can make amends for historic wrongs.

Two centuries after the Parthenon Sculptures were transported to London, there is reason to be optimistic that a solution will be found in the not-too-distant future. People on both sides of the fence are working hard to find a way out of the deadlock. Speaking to the UK press at the end of 2022, the General Director of the Acropolis Museum, Nikolaos Chr. Stampolidis, struck the perfect diplomatic note, echoing the sentiments of the late, great Melina Mercouri, who started the restitution campaign 40 years ago: “If there were a solution, Britain could be the protagonists of an ethical empire because this transcends our countries. If the marbles were reunited here in Athens, within view of the greatest symbol of democracy, it would be a great act for humanity.”

© Acropolis Museum

© Acropolis Museum

© Acropolis Museum

STEPHEN FRY

Member of the Parthenon Project’s Advisory Board, said:

“It’s heartening to see the Parthenon Sculptures thrust into the public spotlight, albeit because of the Prime Minister’s recent dubious diplomatic decision. It’s clear that policymakers, the British public, and the media are increasingly supportive of calls to return these magnificent artifacts to Athens where they can be reunified as an artistic work and displayed most appropriately in the context of the Acropolis.

“To make that vision a reality, we must move the debate away from the quagmire of the past and towards an imaginative future. That means agreeing to disagree on the notion of ownership and delivering a deal that is both mutually enriching for both Greece and the UK and possible under the current law. We have proposed a landmark cultural partnership that would see the Sculptures reunified in Athens while other blockbuster artifacts come to the British Museum for rotating exhibitions, enhancing the museum’s cultural contribution.

“Our approach would also see a non-profit foundation established that would bring opportunities to young people and local communities and serve as a vehicle to drive much-needed fundraising for the refurbishment of the British Museum and the development of a new Hellenic Gallery with state-of-the-art technology that can be used to attract new visitors. This could be mirrored in Greece, with funding directed there towards the wonderful National Archaeological Museum. A forward-looking deal such as this goes beyond merely proposing an exchange of artifacts … [to become] a cultural collaboration that would inspire the next generation of classicists.” (Originally published in Kathimerini)