A Sweet Walk Through Athens’ Most Beloved Pâtisseries

We visit some of Athens’ classic...

A view of the surviving sculptural elements of the east pediment and metopes, including panels depicting the Gigantomachy - the battle between the Olympian gods and the giants for control of the universe.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Over the past year, the media frenzy surrounding the campaign for the return of the Parthenon Marbles has reached fever pitch. While Greek government officials, heritage professionals and members of the international academic community continue to exert unprecedented pressure on the British Museum in London, where Pheidias’ sculptures have been on permanent display since 1817, media outlets and members of the general public, in the United Kingdom and around the world, have been adding their voices to the deafening chorus of calls to reunite the 5th-century BC sculptures in Athens.

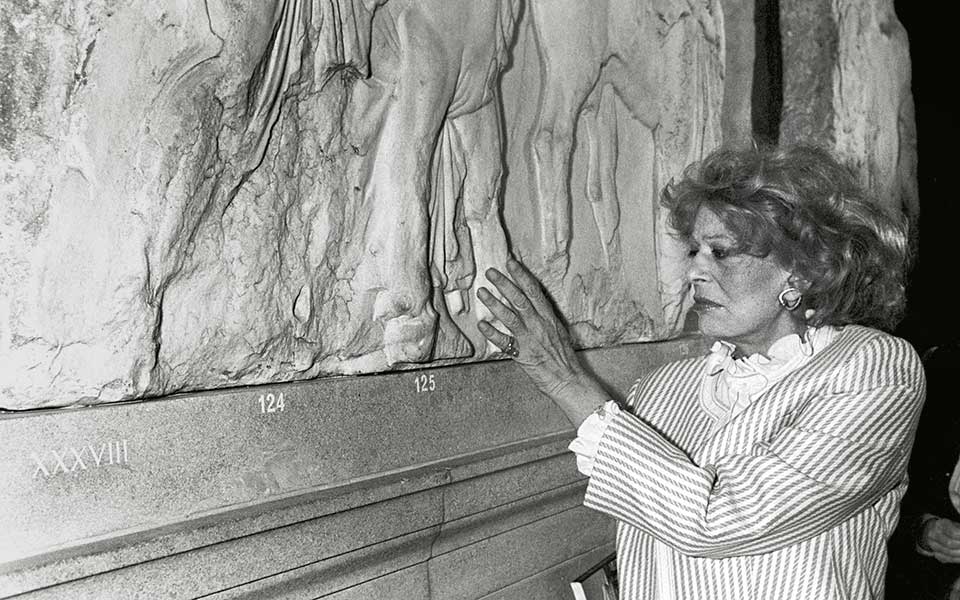

For the first time since the launch of the reunification campaign by the indomitable Melina Mercouri in 1982, UNESCO has urged the UK to review its position on the issue and enter into discussions with the Greek state at an intergovernmental level. There has been a seismic shift in public attitude, too. According to the latest public opinion polls, respondents are resolutely in favor of returning the sculptures to Greece.

And in an astonishing about-face, the London Times, which was staunchly in favor of the British Museum retaining the sculptures in London, changed its stance, arguing that “times and circumstances change.”

Whatever the circumstances regarding Lord Elgin’s removal of the sculptures at the beginning of the 19th century, the writing’s on the wall for their long-awaited return to their place of conception, some 2,500 years ago. As we review the events of the past 12 months, all eyes are now on the UK government and trustees of the British Museum to right this historic wrong.

Agents of Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin, removing sculptures from the Parthenon.

© IN SEARCH OF GREECE. CATALOGUE OF AN EXHIBIT OF DRAWINGS AT THE BRITISH MUSEUM BY EDWARD DODWELL AND SIMONE POMARDI FROM THE COLLECTION OF THE PACKARD HUMANITIES INSTITUTE, 2013

The year 2021 was an auspicious one for Greece, marking the bicentenary of the start of the Greek Revolution, which set Greeks on the path to independence. Six months after the bicentennial celebrations, held on March 25, Greece had another cause for celebration regarding the decades-long campaign to reunite the Parthenon Sculptures in Athens.

In September 2021, Greek government officials made a significant breakthrough at the 22nd session of UNESCO’s Intergovernmental Committee for Promoting the Return of Cultural Property (ICPRCP) in Paris. In a potentially game-changing development, the committee acknowledged for the first time in the near 40-year campaign that the dispute is an intergovernmental one between the Greek state and the UK, and not with the trustees of the British Museum. In their decision, reached by unanimous vote, the ICPRCP made clear its full support for Greece’s legal and moral claims for the sculptures to be returned, and urged “the United Kingdom to reconsider its position and enter into a bona fide dialogue with Greece.”

With fresh impetus, Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis raised the issue in his first official visit to the UK on November 16, 2021. Having pressed his British counterpart, Prime Minister Boris Johnson, in their discussion, Mitsotakis made it clear to the Greek press immediately after the meeting that the return of the sculptures was important for bilateral relations between the two countries: “We will methodically insist on building the necessary foundations and impress upon British public opinion the need to reunite the sculptures of the Acropolis Museum.”

The Greek PM continued to apply pressure four days later in a sagacious article for the Mail on Sunday, citing Boris Johnson’s much-vaunted classical education at Oxford: “More than most, Boris Johnson understands the unique bond that ties modernity to ancient history.” Evoking the great British poet and philhellene Lord Byron, he reminded readers of the centuries-old relationship between Britain and Greece, the crucial role Britain played in the Greek struggle for independence, and called on Johnson, whom he called a “true philhellene,” to seize the moment to “overturn an injustice that weighs heavy in all Greek hearts” and “amend the relevant legislation to allow the sculptures’ return.”

A meeting between the Greek PM Kyriakos Mitsotakis and UK PM Boris Johnson.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

In the wake of the Greek PM’s visit to London, the issue of the Parthenon Sculptures was thrust back into the limelight, not only in Britain but around the world. A petition was soon launched on the UK Government and Parliament website, calling for the government to amend the British Museum Act 1963, and be more responsive for global calls for cultural artifacts acquired during Britain’s colonial era to be returned to their places of origin.

The strong momentum in favor of the Greek position was also reflected in the opinion polls. In a survey by the London-based polling firm YouGov, conducted on November 23, 2021, fifty-nine percent of UK citizens answered that they believe the sculptures “belong to Greece.” Only eighteen percent said the opposite, while twenty-two percent of respondents said they had no opinion.

Writing in the Guardian, historian and columnist Simon Jenkins argued that the debate has been further altered by recent advances in 3D printing and etching technology, pioneered in Italy and at Oxford University’s Institute for Digital Archaeology. This technology is now being used to recreate, with “microscopic accuracy,” ancient statues and monuments, such as Palmyra’s Temple of Baal in Syria, destroyed by ISIS in 2015. As such, Jenkins argued that the British Museum is fast running out of excuses for keeping the sculptures in London: “The Parthenon marbles could now be reproduced as indistinguishable from the originals, even if snooty art critics can dismiss them as fakes and ‘not the same thing.’”

Most significantly, a leading article in the London Times on January 11, titled “The Times view on the Elgin Marbles: Uniting Greece’s heritage,” the newspaper made a spectacular U-turn on the issue: “For more than 50 years, artists and politicians have argued that artefacts so fundamental to a nation’s cultural identity should return to Greece. The museum and the British government, supported by The Times, have resisted the pressure. But times and circumstances change. The sculptures belong in Athens. They should now return.”

Elements of surviving statuary from the west pediment and metopes, on display in the Parthenon Gallery at the Acropolis Museum.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

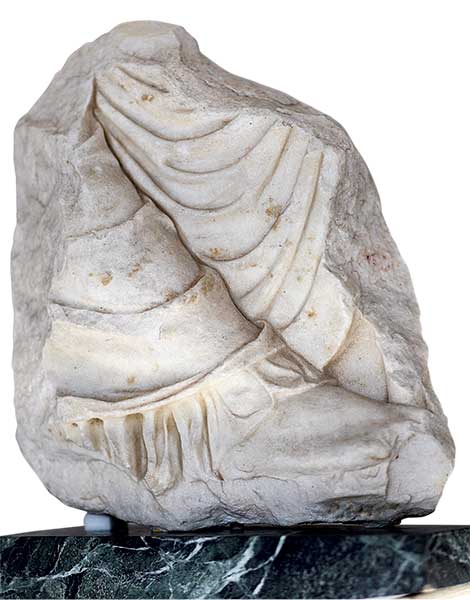

The start of 2022 saw another leap forward in the campaign. In a symbolic gesture at the beginning of January, the Antonino Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo, Sicily, announced a long-term loan of the so-called “Fagan fragment,” a piece depicting the right foot of a draped figure of Artemis, goddess of the hunt. The marble fragment, originally located on the eastern side of the 160m-long frieze that ran around the temple, was once part of the private collection of Robert Fagan (1761-1816), onetime British consul for Sicily and Malta.

In exchange for the fragment, the Acropolis Museum loaned a 5th-century BC marble statue of Athena and a terracotta amphora in the linear, geometric style from the mid-8th century BC.

The initial agreement was for an eight-year loan but, in a joint statement by the Greek Ministry of Culture and the Regional Government of Sicily five months later, the loan became permanent. “The final repatriation to Athens of the Fagan fragment shows the clear and moral way for the return of the Parthenon Sculptures to Athens,” said Culture Minister Lina Mendoni. The fragment was reunited with Block VI of the east frieze in a formal ceremony held at the Acropolis Museum on June 4. In a statement, the museum described the dialogue between Greece and Italy as the result of “love and friendship” and the return of the fragment as a gesture of “their faith in the contribution of the classical Hellenic civilization to the history of humanity.”

In a separate move, the ministry approved the return of ten sculptural fragments that had previously been kept in the storerooms of Greece’s National Archaeological Museum in Athens for display at the Acropolis Museum. The fragments, depicting parts of human figures from the Parthenon’s eastern and southern frieze and its northern metopes, and parts of a head from the northern frieze, were located, identified and documented by the late archaeologist and researcher of ancient Greek sculpture Giorgos Despinis. In a formal ceremony on January 3, they were reunited with the sculptures on display in the specially-designed Parthenon Gallery, in direct view of the Acropolis.

A protestor in London uses humor in her message for the reunification of the Parthenon marbles.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

The Fagan fragment, depicting the right foot of the goddess Artemis, had been at the Antonio Salinas Archaeological Museum in Palermo since 1836.

© Reuters/Alkis Konstantinidis

On April 29, amid mounting pressure from the rising tide of calls to intervene on the issue, Britain’s under-secretary of state for arts, Stephen Parkinson, sent a formal request for a meeting with his Greek counterpart, Lina Mendoni, to discuss the future of the sculptures. According to a subsequent UNESCO announcement, the two sides had agreed a meeting at a ministerial level that would be arranged “in due course.”

News of a potential break in the deadlock clearly put the trustees of the British Museum on the defensive. Two weeks later, at the 23rd session of UNESCO’s ICPRCP in mid-May, the deputy director of the British Museum, Dr Jonathan Williams, made the astonishing claim that much of the statuary removed by Lord Elgin had in fact been retrieved from the rubble around the Parthenon, and not all hacked from the monument.

Campaigners were quick to issue their rebuttals, including renowned Cambridge University archaeologist Anthony Snodgrass, who cited eyewitness accounts of the sculptures being “violently detached” from the monument. Williams’ claim was also dismissed by Mendoni: “Over the years, Greek authorities and the international scientific community have demonstrated with unshakeable arguments the true events surrounding the removal of the Parthenon Sculptures. Lord Elgin used illicit and inequitable means to seize and export the Parthenon Sculptures, without real legal permission to do so, in a blatant act of serial theft.”

The Fagan fragment was reunited with Block VI of the east frieze in a formal ceremony at the Acropolis Museum on June 4, 2022.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

In an article in the Guardian on May 23, Williams admitted that the monuments of the Acropolis are wonderfully preserved and exhibited in Athens’ Acropolis Museum, which opened in 2008, but added: “There will never be a magic moment of reunification because half of the sculptures from the Parthenon are lost forever, half of the sculptures were destroyed by the late 17th century long before Elgin was active in Athens.”

For many in this campaign, the British Museum’s stubborn refusal to admit Elgin’s blatant moral and ethical wrongdoing in the early 19th century, and the part it continues to play in effectively compounding the crime, is doing irreparable damage to the already bruised reputation of the venerable museum. Speaking at the annual Hay Festival in Wales on May 29, actor-author Stephen Fry, a long-time proponent of the reunification of the sculptures, made the argument that the British Museum no longer has any substantial arguments for retaining them in London. “Taking the Parthenon Sculptures from Ottoman-occupied Greece is like the Americans taking the Eiffel Tower from Paris when the ‘City of Light’ was under German occupation.”

He summarized the museum’s argument as “‘We [the British] took them legally from the Turks … which was an occupying force.’” He went on to say that “it would be like Stonehenge and Big Ben were missing from our country for hundreds of years and eventually returned to where they belong.”

In an extensive televised report by Britain’s ITV on May 31, Edith Hall, professor of classical studies and ancient history at Durham University, commented: “Most people around the world simply do not understand the British Museum’s arguments. They sound outdated, as if they belong to the 19th and not to the 21st century.” In a latest twist, the British Museum’s chairman, George Osborne, hinted at a compromise. Speaking to London-based radio station LBC on June 15, he said he would support an arrangement where the pieces were shared between London and Athens: “That kind of arrangement: sensible people should come up with something where you can see them in their splendor in Athens and see them among the splendors of other civilizations in London.”

Fighting for the cause: from Melina Mercouri, Greek Minister of Culture in the early 1980s.

© AP Photo/Thomas Daskalakis

While government officials and heritage professionals continue to exert unprecedented pressure from the Greek side, no foreign organization involved in the campaign has been more vociferous in its support than the British Committee for the Reunification of the Parthenon Marbles (BCRPM). Set up in 1983 under the chairmanship of Robert Browning, emeritus professor of Greek at the University of London, the committee boasts a formidable roll call of distinguished scholars, writers, actors and artists, including Professor Paul Cartledge, Dame Janet Suzman and award-winning author Victoria Hislop.

The BCRPM exists to raise awareness of the issue in Britain and abroad, and to apply pressure on the UK government and the trustees of the British Museum. To that end, its most recent action included a staged demonstration inside the British Museum on June 18, marking 13 years since the inauguration of the Acropolis Museum in Athens. In the museum’s Great Court, the largest covered public square in Europe, protesters unfurled banners and Greek flags, calling on the trustees to return the sculptures to Athens.

Back in Athens, on June 27, American singer-songwriter and philhellene Desmond Child staged a spectacular, star-studded rock concert at the ancient Odeon of Atticus Herodes. In front of a packed audience at the Roman-era Odeon, located on the southwest slope of the Acropolis, A-listers from Greece and abroad, including Alice Cooper, Bonnie Tyler, Rita Wilson and Sakis Rouvas, performed some of Child’s most emblematic songs at the pro bono event, “Desmond Child Rocks the Parthenon.” The concert was a stunning success, reflecting the current state of public sentiment and international support in favor of the reunification of the sculptures.

Desmond Child's awareness concert

© VISUALHELLAS.GR

Since September 2021, the decades-long campaign has been reinvigorated like never before. In the wake of this new momentum, many will be forgiven for thinking that, if the pressure continues, the sculptures will return to Athens in the not-too-distant future. As Simon Jenkins asked in the Guardian last November: “One day, a British government will return the Parthenon marbles to Athens. The only question is: who will obtain Greece’s undying credit and thanks?”

Whatever the legalities of Lord Elgin’s removal of the sculptures in the early 19th century, there can be no denying their cultural importance to the Greek nation. Their return would be a fitting gesture of the UK’s affection and respect for Greece and its people.

We visit some of Athens’ classic...

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...

Mimosa shrubs and sweet acacia and...

The workshop of famed tile painter...