Reuniting the Parthenon Sculptures: A New Chapter in...

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...

Dismembering the Monument: The removal of the Parthenon sculptures by agents of the British Ambassador to the Ottoman Empire, Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin. From the book "In Search of Greece," catalogue of the Exhibit of Drawings at the British Museum by Edward Dodwell and Simone Pomardi, from the Collection of the Packard Humanities Institute, 2013.

Before taking up his post as ambassador to the seat of the Ottoman Empire, an appointment that he had enthusiastically lobbied for, Elgin approached British government officials about the acquisition of drawings and plaster casts of surviving sculptures from the Acropolis monuments; a request that was immediately turned down. At the time, he had been overseeing the redesign of Broomhall House, the family home of the Earls of Elgin in Dunfermline, Scotland. Chief architect on that project was Thomas Harrison, an admirer of Classical Greek architecture, who encouraged Elgin to use his elevated position in the diplomatic service to bring back drawings and casts to be used to influence the design and aesthetic of the country house.

Without official backing from the British government, Elgin decided to go it alone. When he arrived in Greece in 1800, Athens was a ramshackle city of some 10,000 souls, living in poorly built houses around the slopes of the Acropolis. His arrival ignited a great deal of excitement among the local population, hoping that he would create jobs and generate wealth in the impoverished city.

His initial aim was to draw and make casts of the 5th century BC sculptures, as requested by Harrison. At the time, the Athenian Acropolis was still an Ottoman stronghold under the control of the dizdar, the fortress commander. Alongside him was the voivode, the governor of the city and official representative of the sultan, Selim III. Both were well aware of the fascination and allure the monuments of the Acropolis had on Western visitors, especially young gentlemen-scholars on the obligatory grand tour, and neither were opposed to selling the odd piece of sculpture to line their own pockets – an activity that was officially forbidden under Ottoman law.

Nevertheless, the citadel was a heavily fortified military site, and Elgin’s first request to sketch the monuments was turned down. Apprehensive about Elgin’s intentions, the dizdar demanded he obtain formal permission from the top, a royal decree, or firman, from the sultan himself.

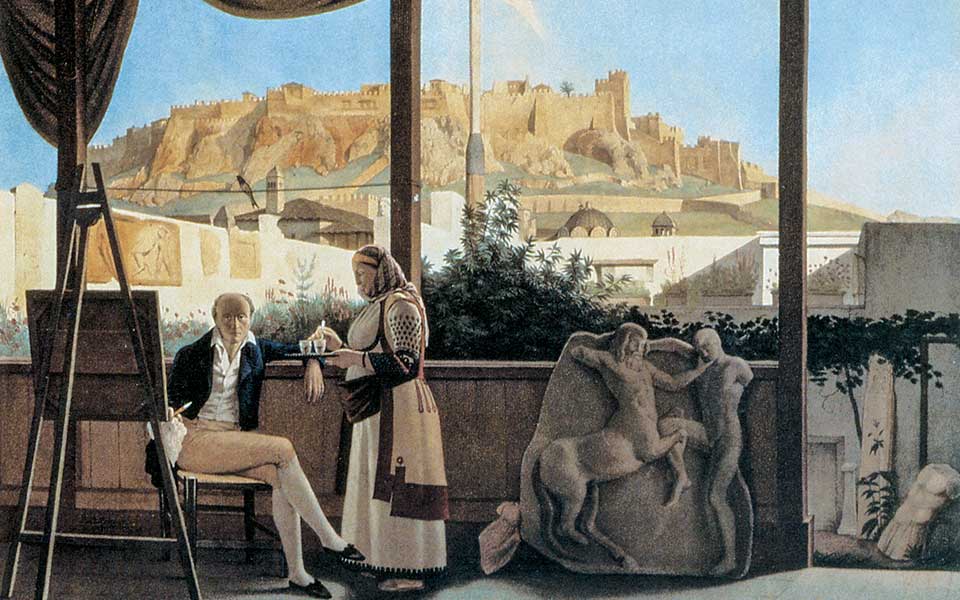

Classical-centric Western Europeans: The view of the Acropolis from the house of French consul M Fauvel. Oil on canvas painting by Louis Dupré, 1819.

© Gennadius Library - American School of Classical Studies at Athens

Leaping to the task, Elgin navigated the labyrinthine layers of Ottoman officialdom in Constantinople and lobbied the sultan for special permission to gain unfettered access to the Acropolis and its monuments. What happened next is crucial to our understanding of the legality of Elgin’s actions.

He claimed to have obtained the official firman in May of 1801, allowing him to erect scaffolding, draw and make molds of the sculptures, but was unable to produce the original document to the officials in Athens. In its place, he presented an English translation of an Italian copy made at the time, deemed insufficient by the dizdar and voivode.

Elgin’s associate Reverend Hunt, a skillful negotiator, then requested a second firman, which he claimed was issued in July of the same year. An Italian transcript of this document still exists in the archives of the British Museum, but its authenticity as a copy of an official firman has been questioned by experts on the diplomatic language used by Ottoman authorities of the period. The wording of the document, not altogether clear, granted Elgin permission to “take away some [or ‘a few’] pieces of stone with old inscriptions or figures thereon, that no opposition be made thereto.”

A landmark 1967 study by British historian William St Clair, “Lord Elgin and the Marbles,” concluded that the sultan likely meant the removal of artifacts that had fallen to the ground and/or been found in excavations at the site, not the artworks still adorning the temples. Nevertheless, in Elgin’s view, it amounted to official permission to remove the sculptures from the Parthenon itself.

The removal of the Sculptures from the Pediments of the Parthenon by Elgin. Watercolor painting by Sir William Gell, 1801.

© Benaki Museum

Presenting the alleged firman to the voivode in Athens, along with the customary bribe, Elgin and his associates immediately set to task erecting the scaffolding and removing the statues and reliefs from the Parthenon. In August of 1801, the British scholar and travel writer Edward Daniel Clarke was an eyewitness to the destructive removal of the metopes. In his “Travels Part II,” he wrote that the dizdar protested their removal but was bribed to allow it to continue:

“We saw this fine piece of sculpture raised from its station between the triglyphs: but while the workmen were endeavoring to give it a position adapted to the line of descent, a pair of adjoining masonry was loosened by the machinery; and down came the fine masses of Pentelican marble, scattering their white fragments with thundering noise among the ruins. The Disdar, seeing this, could no longer restrain his emotions; but actually took his pipe from his mouth, and, letting fall a tear, said in a most emphatic tone of voice ‘Telos!’ [‘Enough!’], positively declaring that nothing should induce him to consent to any further dilapidation of the building.”

In a recent interview, the Honorary Director General of Antiquities and Cultural Heritage in Greece, Elena Korka, an expert on the Parthenon sculptures, asserted that Elgin became increasingly avaricious and used whatever means possible to acquire the sculptures: “He circulated rumors that he had a ‘firman’ from the sultan, when in fact he had a letter from an official not authorized to give permission.”

It’s important to note that the original version of the document Elgin claimed was a firman, surrendered to Ottoman officials in Athens at the time, has never been found.

Lord Byron, the most famous British philhellene, was an outspoken critic of Lord Elgin.

Lord Byron actively participated in the Greek Revolution, losing his life in Messolonghi on April 19, 1824. Oil on wood painting by Ludovico Lipparini, c. 1850.

The excavation and removal of the sculptures and their shipment to Britain was finally completed in 1812, at huge personal cost to Elgin. In total, he paid an estimated £75,000, equivalent to nearly £5 million in today’s money. He intended for the sculptures to adorn Broomhall, his home mansion in Scotland, but a costly divorce from his wife, Mary Nisbet, in 1808 forced him to seek buyers for the sculptures to settle his debts.

Elgin’s initial efforts to sell the collection to the British Museum were unsuccessful, and Britain’s Parliament, conscious of public criticism, showed little interest in stepping in to take them off his hands. His chief critic was the English poet and peer, Lord Byron, who denounced Elgin as a vandal and immortalized the heinous act in his vitriolic poems The Curse of Minerva and Childe Harold’s Pilgrimage.

Byron would later go on to become one of the greatest supporters of the Greek Revolution, taking an active role in the armed struggle before dying in Messolongi in 1824.

The Parthenon Sculptures in London: The temporary Elgin Room at the British Museum. Oil on canvas painting by Archibald Archer, 1819.

© Nicholas Economou / AFP / visualhellas.gr

The subject of the removal of the Parthenon sculptures remained deeply controversial, with scholars, artists and poets taking opposing sides in the public debate. But with growing public interest in Classical Greek art and architecture, the British Parliament soon reconsidered its position. Following an investigation, a parliamentary hearing in 1816 exonerated Elgin’s actions and voted 82–30 in favor of purchasing them “for the British nation.”

The debate concluded that Elgin was right to remove the sculptures as the Ottoman Turks viewed the monuments with apathy, and large quantities of marble had already been used to build the military garrison. Even so, Member of Parliament Hugh Hammersley, who voted against the motion, proposed that “Great Britain holds these marbles only in trust till they are demanded by the present, or any future, possessors of the city of Athens; and upon such demand, engages, without question or negotiation, to restore them.”

Following their sale to the British government for the sum of £35,000, less than half of what it cost Elgin to procure them, the sculptures passed into the trusteeship of the British Museum, where they were put on display to the general public as the “Elgin Marbles,” soon drawing large crowds. They were moved to the specially constructed Elgin Saloon in 1832, where they later underwent several destructive attempts to clean the dust and soot from the deteriorating marble surfaces.

In 1838, while art conservation was still in its infancy, scientist Michael Faraday applied carbonated and caustic alkalies to loosen the dirt, followed by a diluted solution of nitric acid. This not only discolored the marble but also left much of the grime embedded in its cellular surface.

Statuary from the east pediment of the Parthenon, on display in the Duveen Gallery at the British Museum.

© Nicholas Economou / AFP / visualhellas.gr

More destructive cleaning was carried out a century later in 1937-1938 at the instruction of Lord Duveen, a controversial art dealer who was financing the construction of a new gallery at the museum to exhibit the sculptures. This was done under the false belief that the sculptures were originally a pure, brilliant white.

Made from Pentelic marble, the surface would have gradually acquired a color similar to the soft hue of honey when exposed to air, referred to as its natural patina. Using metal scrapers, wire brushes, chisels and highly abrasive carborundum stones, a team of masons worked to remove the patina, scrapping away as much as 2.5 mm of the original surface.

To make matters worse, it is known that the sculptures were originally painted with bright colours. As a result of the excessive cleaning, future scientific studies will no longer be able to determine their original color.

Renewed negotiations, shifting public opinion and...

Two centuries of dispute, diplomacy and...