Disability in Ancient Greece: Myths, Facts, and Accessibility...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

The so-called "Peplos scene" - the centerpiece of the ritual offering to the goddess Athena - was the climax of the Panathenaic Festival. Block V from the east frieze of the Parthenon, c. 447–433 BC.

© Public domain

As the golden rays of the summer sun drenched the marble monuments and civic buildings of Athens, its inhabitants and visitors alike would gather, brimming with anticipation, to partake in one of the most splendid spectacles of the ancient Greek world: the Panathenaic (“all-Athenian”) Festival, or Panathenaia.

This grand festival, celebrated annually and with even greater fervor every four years as the “Great Panathenaia,” was more than just a religious observance of Athena’s birthday, the goddess of wisdom, war, and the protector of the city; it was a unifying force, a conspicuous display of civic pride, and a testament to the enduring might of Athens.

Bust of Athena, type of the “Velletri Pallas” (inlaid eyes are lost). Copy of the 2nd century AD after a votive statue of Kresilas in Athens (c. 430–420 BC). On display at the Glyptothek Munich.

© User:Bibi Saint-Pol / Public domain

"Theseus Slaying Minotaur" (1843), bronze sculpture by Antoine-Louis Barye. According to Greek mythology, the divine hero Theseus was the founder of Athens.

© Antoine-Louis Barye / Public domain

While modern scholars agree that the inaugural celebration of the Panathenaic Festival took place in 566 BC, its earliest origins are likely to be far older, with roots in Greek mythology. According to a popular tradition, the festival was founded by the mythical king Erichthonius, son of Gaia (Earth) and Hephaistos, or, in other versions, by the legendary hero and lawgiver Theseus (of Minotaur fame), who is credited with uniting the various tribes of Attica under Athenian rule — a process known as “synoikismos” (“dwelling together”). In his “Life of Theseus,” 2nd century AD Greek historian Plutarch noted that this unification of the Attic tribes was a crucial moment in the development of the city-state – “thus making one people of one city” (Plut. Thes. 24.1) – with the Panathenaia serving as a symbol of this newfound unity and the shared devotion to Athena.

In its earliest form, the festival was a modest event, primarily religious in nature, focusing on sacrifices and offerings to the goddess. However, by the mid-6th century BC, under the influence of the tyrant Peisistratos (c. 600-527 BC), the Panathenaia was significantly expanded and embellished. Peisistratos recognized the festival’s potential to enhance the city’s prestige throughout the Greek world. He introduced the “Great Panathenaia” in 566/5 BC, a more elaborate version of the festival held every four years, which included athletic competitions, musical contests, and a grand procession through the city.

The Great Panathenaia quickly became one of the biggest and most important festivals in the ancient Greek calendar, attracting participants and spectators from across the Greek-speaking world. While the annual (or Lesser) Panathenaia retained its religious and civic functions, the Great Panathenaia added layers of cultural and athletic splendor, serving as both a religious celebration and a showcase of Athenian power and superiority.

The Ancient Agora of Athens

© Shutterstock

The month of “Hekatombaiōn” (July-August; the first month of the Attic calendar), when the Panathenaia was held, transformed Athens into a vibrant hive of activity. The city’s Agora, nestled at the foot of the Acropolis, buzzed with the energy of traders, artisans, and local farmers, all busily preparing for the festival. The sweet scent of honey cakes mingled with the rich aroma of roasted meats and the earthy tang of fresh fruits, filling the air with the promise of feasts to come. Crowds thronged the streets, from humble peasants to the city’s aristocrats, all converging on the Acropolis, the very heart of the festivities.

Communal feasting was an essential part of the Panathenaia. Hundreds of animals, primarily cattle, were sacrificed to Athena over the course of the festival, their meat carved up using a ceremonial “kopis” (curved knife) and shared among the people, of all classes and stations. The opening banquet took place during the first night in the Agora, under the watchful gaze of Athena’s Parthenon, followed by another large gathering on the second day.

The great “Hekatomb,” the sacrifice of a hundred cattle that took place at the end of the festival, would have been a sight to behold, with the fires of the altars burning brightly against the backdrop of the evening sky.

Imagine the scene: the Acropolis bathed in the glow of countless torches, the aroma of roasted meat filling the air, and the sound of laughter and song resonating through the city. This was more than just a meal; it was a celebration of unity, a time when the divisions of class and wealth were momentarily set aside, and all Athenians, from the poorest citizen to the wealthiest aristocrat, shared in the bounty.

This preserved section of pavement, near the agora’s Acropolis entrance, marks the path of the Panathenaic Way.

© Shutterstock

The most important aspect of the Panathenaia was a religious procession, known as the “pompe.” The sacred road from the Dipylon Gate, the main gate of the old city walls in the Kerameikos, to the Acropolis was lined with crowds of eager onlookers, each vying for a view of the spectacle. This route, called the Panathenaic Way, still exists today, winding through the Agora and leading up to the Acropolis. The air was alive with the rhythm of flutes and lyres, the clatter of hooves, and the murmurs of the crowd. At the head of the procession walked young maidens, the “kanephoroi,” who gracefully carried baskets of barley and ribbons destined for the sacrifices. Following them were the bearers of the “peplos,” a richly embroidered robe that was the centerpiece of the ritual offering to Athena. The robe, adorned with scenes of Athena’s triumphs, was carried with reverence to the Erechtheion, the ancient temple on the north side of the Acropolis where the olive-wood cult statue (“xoanon”) of Athena Polias – “Athena of the City” – resided.

The grandeur of the Panathenaic Procession was immortalized in the Parthenon frieze, a 160-meter-long marble relief that encircled the inner chamber of the Parthenon. This masterful work of high-relief sculpture, overseen by Pheidias (c. 480-c. 430 BC) in the second half of the 4th century BC, vividly depicts the various elements of the procession, from the stately march of the kanephoroi and the sacrificial animals to the cavalcade and the presentation of the peplos to Athena. Today, nearly half of the surviving fragments of this frieze can still be admired in the Acropolis Museum in Athens, offering a window into the splendor of the ancient festival. The remaining half currently resides in the British Museum.

Greek vase depicting runners at the Panathenaic Games c. 530 BC

© MatthiasKabel / Public domain

In tandem with the religious ceremonies were the Panathenaic Games, which lasted for several days and divided into three age categories: boys (12-16); beardless youths (16-20), and men over 20. These games were not just a showcase of physical strength and skill; they were a tribute to the spirit of competition and excellence that was central to Athenian identity.

The Stadium, situated south of the Acropolis, echoed with the roars of the crowd as athletes took to the field. The “stadion” race, a sprint of about 180 meters, was one of the most eagerly awaited events – a bit like today’s Olympic 100m final. The intensity of the moment as the runners took their marks can still be imagined today when visiting the Panathenaic Stadium (“Kallimarmaro,” literally “beautiful marble”) in Pangrati, built over the site of a late 5th-century/early 4th-century hippodrome (racecourse). What is visible today comes from the later rebuild of the original stadium, commissioned by the Athenian Roman senator Herodes Atticus (101-177 AD) in the mid-2nd century AD. Excavated and heavily refurbished in the 19th century, it hosted the first modern Olympics in 1896 and featured again as an Olympic venue in 2004.

In addition to the track events, the games included wrestling, boxing, and the “pankration” – a brutal blend of boxing and wrestling that tested the limits of human endurance. Victors were crowned with olive wreaths, but their true prize was the honor and recognition that came with victory.

The equestrian events were a particular highlight. The thunder of hooves filled the air as chariots raced around the track, drivers deftly maneuvering their horses through tight turns. This was a true spectacle, where the wealthy elite of Athens – the “hippeis” (cavalry class) – could display their prowess and wealth, as maintaining horses and chariots was a costly affair.

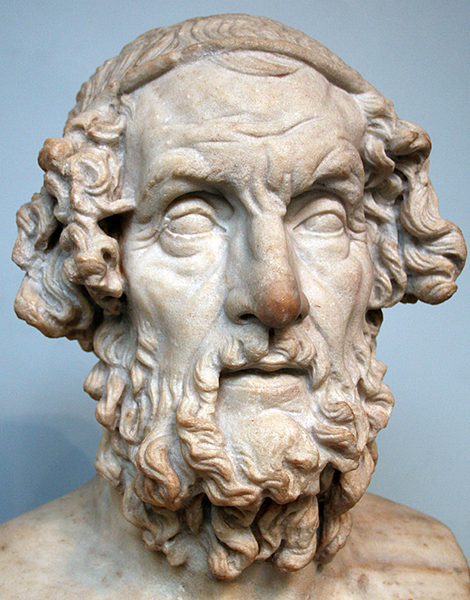

Marble terminal bust of Homer. Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original of the 2nd c. BC.

© Public domain

Athena on a Panathenic amphora (National Archaeological Museum of Athens)

© Ricardo André Frantz / Public domain

Beyond the athletic competitions, the Panathenaia was also a celebration of arts and culture. Poets, musicians, and rhapsodes gathered to recite epic tales, sing hymns, and perform in honor of Athena. These performances were not merely entertainment; they were a reflection of the intellectual and cultural values that Athens prized above all else. The recitations of the Homeric epics, the “Iliad” and the “Odyssey,” in particular, resonated deeply with the Athenian audience, reminding them of their connection to a heroic past and their place in the cultural continuum of Greece.

The Panathenaic amphorae, large ceramic vessels filled with sacred olive oil, were awarded as prizes to victors in both the games and the artistic competitions. These amphorae were not just utilitarian; they were beautiful works of art, decorated with scenes of the competitions and images of Athena. The finest potters and painters of Athens contributed to their creation, making these vessels highly coveted both within and beyond the city. These amphorae, some of which can be seen in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens today, are a testament to the artistic and cultural achievements of the ancient Athenians.

Temple of Athena: The Parthenon, visual centerpiece of the Athenian Acropolis, amid scattered architectural remains of shrines and dedications that once adorned the Sacred Rock.

© Shutterstock

While the annual Panathenaia was a significant event, it was the Great Panathenaia, held every four years, that truly captured the grandeur of Athens. The Great Panathenaia included all the elements of the annual festival but on a much larger scale and three to four days longer in duration. The athletic competitions were expanded to include events open to non-Athenians, attracting competitors from across the Greek world. Musical contests were more elaborate, and the procession was more splendid, with delegations from allied cities participating.

The Great Panathenaia, with its expanded competitions and more elaborate ceremonies, was a demonstration of Athenian superiority. By inviting participants from across the Greek world, Athens not only showcased its wealth and cultural achievements but also reinforced its role as the leader of the Hellenic world.

One of the most significant additions to the Great Panathenaia was the “Panathenaic ship,” a wheeled float shaped like a trireme (oared warship), which carried the peplos during the procession. This ship symbolized Athens’ naval power and was a visual reminder of the city’s dominance.

The Panathenaic Stadium at dusk.

© Shutterstock

The Panathenaic Festival was more than just a religious event; it was a powerful expression of Athenian identity and pride. It reinforced the city’s values of piety, athleticism, and cultural excellence, and it served as a reminder of the deep bond between Athens and its divine guardian, Athena.

Even today, as the world watches the Summer Olympic Games in Paris, the echoes of the Panathenaic Games can still be heard. The spirit of competition, the celebration of human achievement, and the sense of shared cultural heritage are as relevant now as they were in ancient Athens. The Panathenaia was a festival that brought the city together, a time when the inhabitants of Athens could revel in their shared identity and take pride in their place in the world. The values it celebrated – piety, athleticism, and cultural excellence – continue to inspire generations, reminding us of the enduring legacy of a civilization that laid the foundations of Western culture.

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

From a mysterious Minoan structure to...

Explore the role of Hestia, goddess...

Discover the lesser-known oracles of ancient...