Island vs Mainland Cuisine: A Dialogue of Sea...

From the salt-sprayed islands to the...

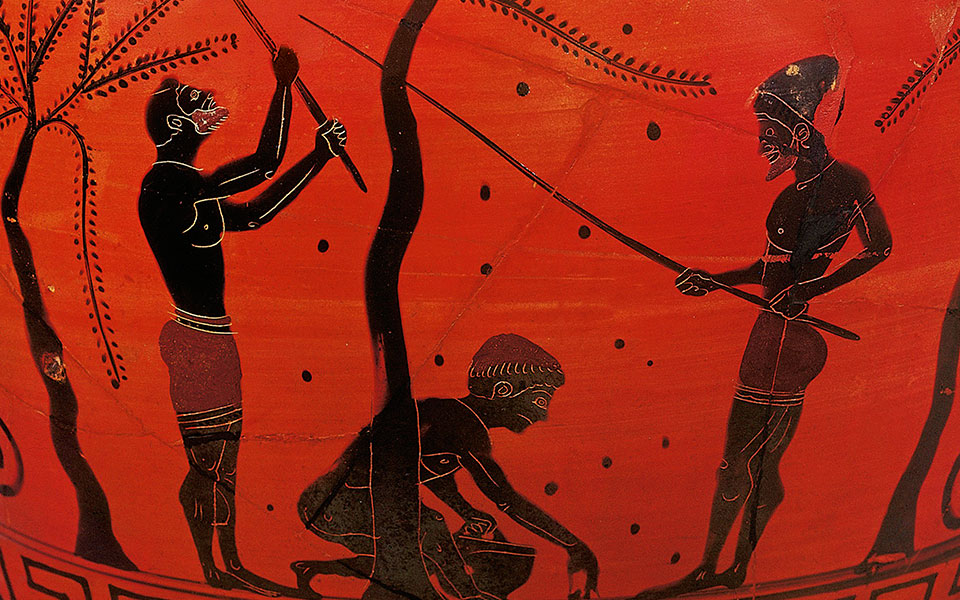

Harvesting olives using long sticks, a technique still seen today. Attic black-figure amphora, 520 BC (British Museum).

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Ιt might seem strange today,” Georgios Glentousakis admits as he explains that he has been an olive farmer since 1949, when he was 12. He started by helping his family harvest the ripe black olives, beating the branches with sticks to make the fruit fall onto the nets below. Then, he helped bring what they’d gathered up to an old four-stone mill, powered by the family’s horse, where the olives were crushed. At the village press, he watched as fresh streams of oil were squeezed out of the layers of olive paste spread over goat hair mats.

As a teenager, Glentousakis borrowed a magnifying glass from an agronomist and taught himself how to monitor the life cycle of olive flies in order to determine when best to take action against the pest. The older farmers followed his lead. Over the decades, as his grandfather and father planted more olive trees and Glentousakis transformed vineyards into olive groves, he was witness to a transformation in the Cretan olive oil world.

In his lifetime, Glentousakis has seen a progression from the less effective old ways of the past to the cleanliness and efficiency of the bright, stainless-steel machinery he appreciates at modern mills like that of Terra Creta, in the northwest of the island. Today, he’s the oldest of a team of farmers working with Terra Creta to learn how to better protect crops, prune trees, transport olives, save time and resources, and achieve higher yields and better quality extra-virgin olive oil.

Of course, the Greek olive oil tradition extends back much farther than Glentousakis’ own memories. For thousands of years, the silvery-green leaves of olive trees have stretched across valleys and hills and reached up into the mountains. Throughout recorded history, olive oil has been crucial to the Cretan diet and economy, and central to its art, literature, traditions and religion.

Giant nets are spread beneath the olive trees to catch the fruit knocked off the branches during the harvest.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Food traces from a bowl found in Gerani Cave in Rethymno show that Cretans were using olive oil as early as 4500 BC, starting with oil from wild olive trees. Systematic olive tree cultivation seems to have begun around the 3rd millennium BC, in the early Minoan period. Paul Faure has argued that Cretans were the first in the world to cultivate olive trees. Anaya Sarpaki and Nikos Michelakis contend that the Minoans also created the earliest written records and artworks about olive trees and olive oil in the world, such as the tablets, frescoes, vases, amphorae and gold olive-leaf jewelry on view in archaeological museums on Crete and elsewhere.

The island’s mild climate and dry, sunny summers enabled continuous olive cultivation over the centuries. Olive oil’s growing importance, starting around 2000 BC, has been revealed by numerous archaeological finds, including tools, lamps, seeds, olive groves, olive oil mills, art works and ideograms on clay tablets. Olive oil was consumed as a food, used as medicine, preservative, fuel for lamps, body rub, lubricant and perfume, as well as in witchcraft rituals, religious ceremonies and the care of the dead.

Olive oil exports were well-organized when Crete was under Venetian rule in the 17th century, and olive oil was particularly crucial to the Cretan diet during the difficult years of Ottoman rule (17th to 19th centuries). By the 19th century, with the development of the commercial soap industry, olive oil production again became central to the Cretan economy.

The sculptural nature of Crete’s ancient olive trees make them eminently photogenic.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Today, monumental olive trees testify to the lasting importance of this liquid gold in Crete. Cretans claim to have two of the oldest olive trees in the world: the sculpture-like Olive Tree of Vouves in western Crete (probably 2,000 to 3,000 years old) and the ancient Olive Tree of Kavousi in Lasithi, eastern Crete, near the archaeological site of Azoria (believed to be more than 3,000 years old). The internal cavity of the olive tree of Grambela near Kandanos made its own contribution to history as a hiding space for Christians during Ottoman rule and for islanders fleeing German troops during World War II – a period during which, some say, olive oil saved lives by staving off starvation.

Proponents of olive oil insist it does far more than alleviate hunger. “Olive oil is the best for people,” Glentousakis says, and this energetic, white-haired octogenarian appears to be living proof of the claim. Calling for a glass of olive oil as we talked, he explains that he eats rusks with olive oil, honey and graviera cheese every morning, and this gives him the strength to work in the olive groves all day. His doctor, he says, told him this olive oil-rich diet is why he can dance, sing and carry on like a much younger man.

Many recent scientific studies have provided evidence that a diet rich in olive oil provides wide-ranging health benefits – especially extra-virgin olive oil (EVOO), the tastiest and healthiest grade, which Cretans estimate comprises about 90 percent of the olive oil produced on the island.

Emmanouil Karpadakis, export manager at Terra Creta, believes “the olive oil culture of the island is stronger than in any other producing area in the world,” which he considers “obvious, since EVOO consumption is the highest in the world, and EVOO uses are far more advanced and are part of our everyday life.” Estimates of Cretans’ current annual use of olive oil range from 22 to 34 kilograms per person.

Elidia Olive Oil’s Dimitris Chondrakis calls this liquid gold the “backbone of the rural economy in our region and the most important ingredient in Cretan cuisine.” He likens it to salt and pepper as “it is found in any dish, regardless of whether it is fried, cooked or baked.”

Many Cretan specialties, including dakos (pictured here), are incomplete without the liberal application of olive oil.

© George Drakopoulos

Where does all this olive oil come from? It is believed that 55 to 65 percent of the cultivated land on Crete is given over to olive groves, which contain approximately 30 million trees, so that the groves cover one-fifth to one-quarter of the island. The small, hardy Koroneiki olive, which yields a high quality, well-balanced, fruity oil, is the most common variety for oil. Tsounati olives are also traditionally popular for oil in Crete, especially at higher altitudes, since they can withstand lower temperatures. In some parts of the island, Chondrolia (or Throumbolia) olives are grown for both oil and table olives.

Proud of their olives whichever variety they grow, Cretan olive oil producers like Eftihis Androulakis show great respect for nature, and it is this respect, together with tradition and the rugged landscape in many olive-growing areas, which prevents intensive cultivation. Typically small-scale family farmers, most Cretan olive growers use hand-held mechanized harvesters to collect olives. This labor-intensive method is kinder to the environment than highly mechanized harvesting. Androulakis must also climb a mountain to reach his older trees, then clamber up into them to pick the unripe olives he uses in his Pamako EVOO brand.

Crete produces a wide variety of top-quality extra virgin olive oils.

© Katerina Kampiti

While most Cretan olive mills are busiest in November and December, working with olives brought to them in jute bags or in plastic crates packed into pickup trucks, Androulakis has convinced one mill owner to open earlier and work with him on dozens of experiments exploring innovative oil extraction techniques. For example, he has taken the unusual steps of inventing machines he needs, refrigerating olives before extracting their oil, and using the inert gas argon during oil production as well as during storage.

An olive oil lover who has attended seminars and done his own research, too, Androulakis is clearly passionate about his work, but many other Cretan olive oil producers are also embracing the latest scientific developments that can improve their product. The result is some of the world’s healthiest, tastiest extra-virgin olive oil, according to international olive oil competitions around the globe.

These conscientious producers’ efforts make a difference. According to the Association of Cretan Olive Municipalities, the average annual olive oil production in Crete is approximately 80,000 metric tons. As Alkiviadis Kalabokis, president of the Exporters’ Association of Crete, confirms, “Olive oil and its exports have a very important role in Crete’s economy.” In 2016, olive oil exports brought Crete €190 million, amounting to 41.5 percent of Cretan export income and 66 percent of its food and drink export income.

© Shutterstock

However, three-quarters of Crete’s oil export is in bulk, mostly to Italy where it is mixed with other olive oils and bottled. Major players in the Cretan olive oil market have called for more standardization before export, so that consumers worldwide can appreciate the unique flavor and high quality of the island’s olive oil, and Cretans can benefit from the added value of packaged olive oil. Gradually, this call is being heeded, as educated producers like Androulakis help give award-winning, bottled and branded Cretan EVOOs a more prominent place on the world’s stage.

As Kalabokis says, “Crete is distinguished for two sectors; tourism and agri-food.” More and more, the two are being linked in agritourism and in culinary tourism ventures. Impressive monumental olive trees have been mapped, and olive oil museums displaying old tools, machines, containers and photos have opened. Olive mills offer tours, seminars and tastings, restaurants serve Cretan specialties made with local extra virgin olive oil, and shops stock Cretan EVOOs for tourists to take home. On top of that, archaeological finds have revealed secrets from Crete’s ancient olive oil heritage. Increasingly, visitors are discovering that the history of olive oil and the unique stories of its producers are a vital part of the Cretan experience.

Biolea’s small traditional olive oil production center is set in a stunning location.

From the salt-sprayed islands to the...

All the secrets to producing a...

The signature dish of the island...

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...