The Lost Cities of Ancient Greece: Rediscovering a...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

The perfectly-designed Theater of Epidaurus, a work of Polykleitos the Younger in the 4th c. BC.

© Clairy Moustafellou

In the 4th century BC, the injured and infirm had a choice of two different treatment paths to follow when seeking comfort, care and a return to good health. They could go to a temple or a healing sanctuary such as the Asclepieion at Epidaurus, and pursue a traditional, faith-based cure through worship, sacrifices and the dedication of votive objects to Apollo, Artemis, Asclepius, Hygieia and other health gods; or they could approach a Hippocratic physician, who offered practical, science-based treatments involving therapeutic herbs and other medicinal curatives (farmaka).

Asclepius, a god of healing, was a relatively new face among the divine patrons of health, although he had already appeared in Homer’s Iliad (late 8th/early 7th century BC).

Asclepius’ cult emerged more clearly in the 6th, 5th and especially 4th century BC. He was perceived as a more approachable god, concerned with the welfare of ordinary people. His sanctuaries (asclepieia), at Epidaurus, Kos, Athens, Corinth, Pergamon and many other places, became refuges for the ill, places of hope and reassurance, where priests guided them through rituals of purification and “incubation” (enkoimesis) – during which they spent the night in one of the sanctuary’s sacred buildings (abaton) and waited for the god to enter their dreams with a therapy.

Later, with the increasing emphasis on real-world, medicinal treatments, asclepieia began employing physicians who could supplement their priests’ spiritual/mystical curatives with applications of tangible farmaka.

Whether through the body’s own curative powers or the workings of prescribed medicines, many ill visitors to Epidaurus and other asclepieia appear to have been healed, as we learn from inscribed steles describing cases and “miraculous” cures that were publicly erected in the sanctuaries.

The asclepieia became de facto hospitals, serving primarily the injured and infirm who had already been treated unsuccessfully by Hippocratic physicians, or who had been turned away by such doctors during a triage process in which they had been judged to be “helpless” cases.

The official inscriptions heralding cures, combined with the testimony of patients themselves – for example, the personal memoirs (“Sacred Tales”) of Aelius Aristides (2nd century AD) that describe his dream-state encounters with Asclepius during a stay at the Asclepieion of Pergamon – indicate the ailments treated in the sanctuaries ranged from persistent skin rashes and baldness to major internal problems such as abdominal tumors, tapeworms and non-progressive pregnancies.

In a medical approach similar to present-day integrative medicine, the Hippocratic physicians’ care for “treatable” patients and the priests’ attentions to the “helpless” meant that the full scope of the infirm could receive medical assistance through what was essentially a dual but allied public health care system. Modern Jungian scholars, including C. A. Meier and Edward Tick, have suggested that dream-healing like that at the asclepieia represents the ancient forerunner of modern psychotherapy.

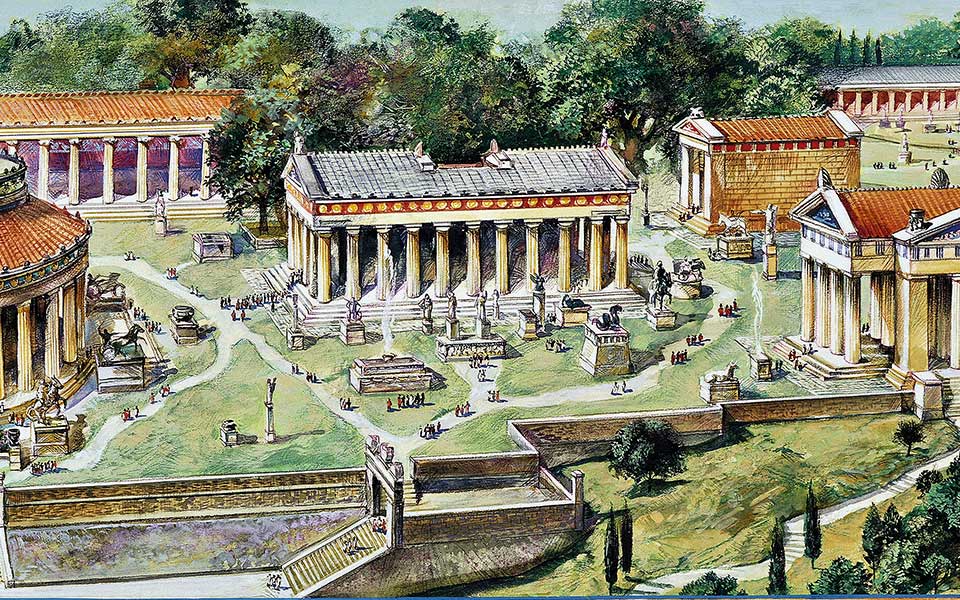

The heart of the Epidaurus sanctuary: the Tholos and the Abaton (left) and the Temple of Asclepius (center right).

© De Agostini/Getty Images/Ideal Imge

The urban environments of ancient Greece, despite early engineers’ efforts at water and sometimes waste management, were relatively unhealthy places, especially under crowded wartime conditions. When visiting Epidaurus, however, situated in the piney, rolling countryside of eastern Argolida (northeastern Peloponnese), one is immediately struck by the area’s open vistas, fresh air and natural forest scents.

This was, and still is, an invigorating landscape, with clear, clean water, plenty of warm winter sunshine and a tranquility only to be found away from the city. It was just such wholesome natural environments that Asclepius’ followers sought when establishing their hospital-like sanctuaries.

In ancient times, visitors to Epidaurus would have approached the Asclepieion from its north end, not from the south as today. They entered the unwalled sanctuary through the Propylaea, a door-less monumental gateway decorated with both Ionic (outside) and Corinthian (inside) columns. It represented a ceremonial checkpoint through which only those who’d first purified themselves at an adjacent sacred well (still visible) could pass.

Inside the sanctuary, the ancient visitor would have passed through the heart of the Asclepieion, following narrow lanes filled with priests, officials, the infirm (and, perhaps, their concerned relatives), all going about their daily business, seeking treatment or making supplications to the gods. Here were found the site’s key buildings, including temples and altars of Asclepius, Artemis and Themis, as well as a shrine possibly dedicated to Asclepius’ daughter, Hygieia, and her siblings.

Most of the buildings at Epidaurus date to the 4th century BC, when the sanctuary underwent major construction work. Asclepius’ temple would have been an impressive Doric edifice, inside which, according to the traveler Pausanias (2nd century AD), was the healing god’s cult statue: “half as big as the Olympian Zeus at Athens … made of ivory and gold … The god is sitting on a seat grasping a staff; the other hand he is holding above the head of a serpent; there is also … a dog lying by his side.”

Nearby, Pausanias continues, was “the place where the suppliants of the god sleep” – the Abaton. This long, Ionic-style building was a colonnaded shelter where another sacred well allowed further purification before the incubation began.

Asclepius, bending forward and extending his arms as he offers therapy to a woman lying on a couch. Behind him is Hygieia, goddess of health. A votive relief of Classical date, from the Asclepieion in Piraeus (Piraeus Archaeological Museum).

© De Agostini/Getty Images/Ideal Image

Beside the Abaton is a mysterious monument of uncertain function, a circular Tholos, with maze-like passages below floor level now hidden inside its restored base. The Tholos’ central location indicates a close association with the Asclepius cult, and Pausanias observed inscribed steles here commemorating cures.

It also may have held Asclepius’ sacred snakes, symbols of rebirth and rejuvenation. In some asclepieia, non-venomous snakes slithered about freely in the visitors’ quarters, while the serpents at Epidaurus, including an odd yellowish variety, were reputedly tame.

At Alexandria, according to Aelian (2nd/3rd century AD), the god’s snakes were gigantic, some reaching 6-14 cubits (3-6m) in length.

Epidaurus’ prototypical Asclepieion shows these sites were not only for religious worship and medical attention, but for athletics, music and theatrical performances as well – popular features at sanctuary festivals. The ancient visitor, walking southward from the Tholos, would have passed the Gymnasium (L), the sunken Stadium (R) and a Greek bathing complex. At the sanctuary’s southeastern corner rises its enormous theater (with a capacity of 13,000-14,000 people), where even the smallest sounds in the orchestra can be heard from the uppermost rows.

Inside the Gymnasium, Roman-era visitors would have glimpsed a brick-and-mortar odeon (music hall) of the 3rd century AD within the then-abandoned athletic facility. Such Roman additions reveal the lengthy lifespan of the sanctuary, which flourished from at least the 6th century BC to the 4th century AD. Ultimately, Goth invasions and increasing Christian pressure left the pagan shrine destroyed, disused and abandoned.

Modern reconstructions of the Gymnasium’s Doric entranceway, the Tholos, the Abaton and the Stadium are all underway or completed. Although controversial (concerning their extent), these partial restorations give the site a sense of vitality and its visitors a clearer idea of the sanctuary’s original scale and architectural elegance.

Strolling among shady pines between the Gymnasium and the Theater, visitors will encounter one of Epidaurus’ most intriguing ruins: the Katagogeion or Guesthouse: a square building subdivided into four quarters, each consisting of a courtyard ringed by 18 accommodation rooms. The well-worn thresholds of these rooms are still in place, and it is easy to imagine the ancient occupants residing within, or stepping outside to sit or lie in the sunlight that would have filled these enclosed, now grassy courtyards.

The Doric-style entranceway to the Gymnasium (4th c. BC), through which many an athlete passed, once again rises skyward.

© Perikles Merakos

The Asclepieion of Kos, with its monumental staircases and temples of Apollo and Asclepius (foreground). Behind them, the large Temple of Asclepius (170/160 BC), once visible to passing ships.

© Giannis Giannelos/Ministry of Culture & Sports/Ephorate of Antiquities of Dodecanese

From the Katagogeion, a path leads to the Epidaurus Museum. Here one finds a display of the evocative inscribed steles recording the Asclepieion’s amazing cures. One entry reads: “Arata, a Spartan, suffering from dropsy. On her behalf her mother slept in the sanctuary while she stayed in Sparta. It seemed to her that the god cut off her daughter’s head and hung her body with the neck downwards. After a considerable amount of water had flowed out, he released the body and put the head back on her neck. After she saw this dream, she returned to Sparta and found that her daughter had recovered and had seen the same dream.”

Another entry describes the war veteran Euippos, who’d had a spearhead lodged in his jaw for six years. After a dream at Epidaurus, however, he awoke with his injury healed and the spearhead in his hand!

Other official inscriptions represent detailed building and financial records, or set out the sacred law that governed an invalid’s access to the sanctuary and called for successfully healed visitors to make a grateful sacrifice to Apollo and Asclepius. One admonitory entry states that a certain Hermon was re-blinded for not paying his due.

Two further galleries illustrate the fine sculptures and architecture of Epidaurus, including elements of the Tholos’ ornate Doric/Corinthian colonnade and its intricate interior decoration. Also featured are displays of bronze medical instruments.

As Asclepius’ cult spread in the 5th-3rd centuries BC, his sanctuaries came to be found in almost every Greek and Roman city or large town. They operated as both public health care facilities and medical teaching centers.

Epidaurus, the healing god’s supposed birthplace, represented the asclepieia network’s “capital,” from which a cult statue and sacred snakes were brought for initial consecration rites whenever a new sanctuary was established.

Asclepieia often arose in response to health crises, such as the outbreaks of plague in Athens (430 BC) and Rome (293 BC), where sanctuaries occupied the South Slope of the Acropolis and Tiber Island respectively. Kos also held a major Asclepieion, staffed by Hippocratic physicians, while the Roman doctor Galen trained at Pergamon.

Notable smaller sanctuaries existed at Corinth, Sicyon, Tegea, Megalopolis, Argos, Sparta and Messene; on the islands of Paros, Aegina and Crete (Leben); and at Alexandria (Egypt) and Cyrene (Libya).

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...

Explore Ancient Messene, enjoy the local...

Ten must-do experiences in Athens, from...

Discover the lesser-known oracles of ancient...