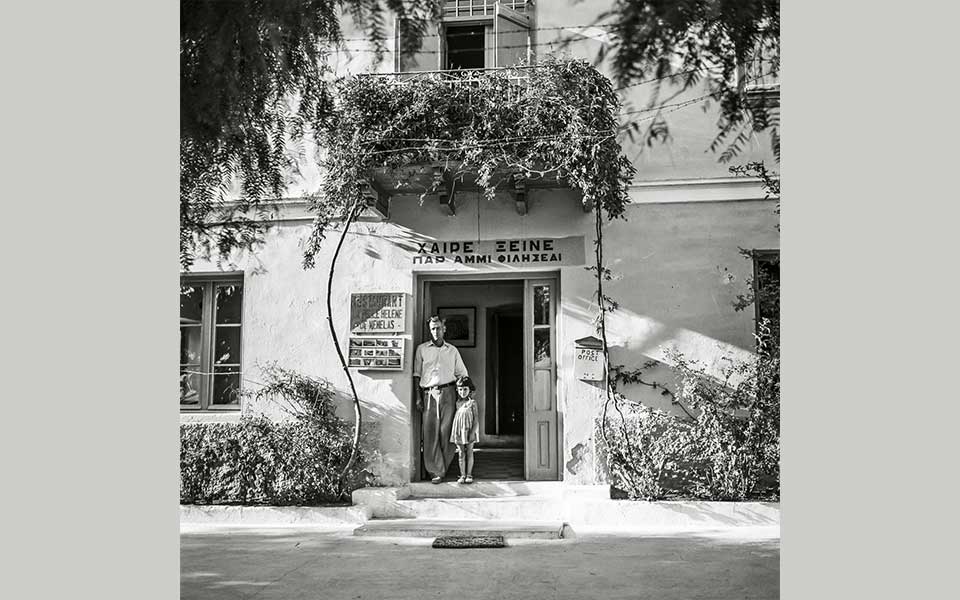

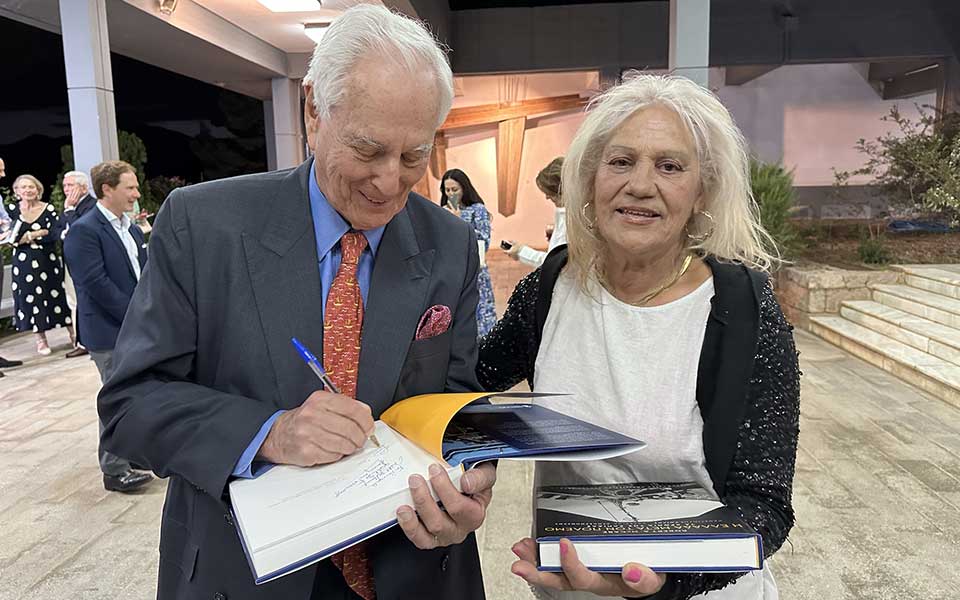

Lula Christopoulou has looked at a certain photograph of herself countless times. Yet, when she came across a blown-up print of it at photographer Robert McCabe’s exhibition at the European Cultural Center of Delphi, she was deeply moved. “Look at how my dad is holding me,” she said. Today, she is 71 years old; in the picture, she is not yet four, and her father, Agamemnon Dasis, has his hand on her shoulder as they stand at the entrance of their family hotel in Mycenae.

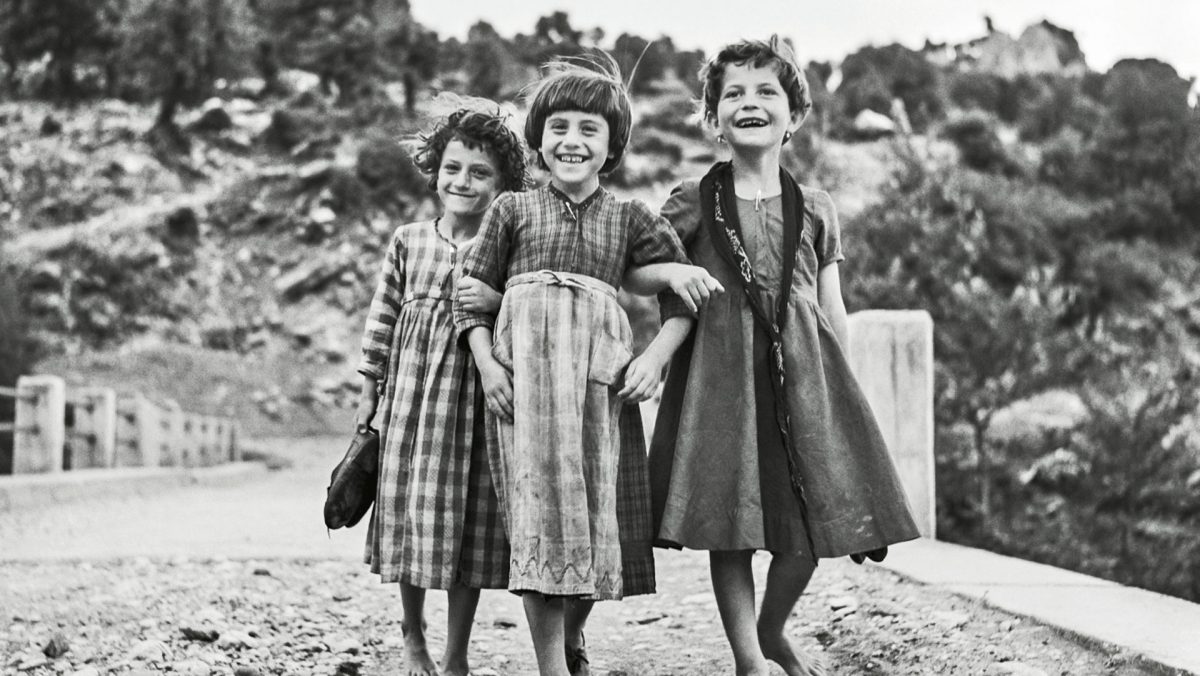

Lambrini Gavrila-Plati first saw her childhood photograph in 2007. McCabe had returned to Epirus for an exhibition and was in search of the three girls, two of them barefoot, who, laughing freely, had posed for him in the Greek countryside in 1961. “I don’t recall him taking our photo, but I do remember the location. We were waiting for our parents to finish their work in the fields, playing on the bridge over the Metsovitikos River. We were holding our shoes rather than wearing them so as not to damage them. Each of us had only one pair,” says Lambrini.

Dimitris Managas, now 94, treasures the photo of him and his wife Toula, taken by Takis Tloupas, as he does many other photos at his home in Thessaloniki, frequently perusing them. “We traveled all over Greece together,” he says of his friend Takis, his voice heavy with memory.

These three photos, epitomizing a Greece on the cusp of transformation, narrate the tale of a different era.

© Robert A. McCabe

Friends Still, After Sixty Years

Lamprini doesn’t remember ever having been gifted a toy during her childhood. However, in her birthplace, the village of Megalo Peristeri in Epirus, northwestern Greece, the abundant presence of other children made toys unnecessary. Together, they were always outside, often without shoes, engaged in hours of hide and seek. “Our parents cultivated wheat and corn, so we were never hungry, but luxuries were beyond our means. Nonetheless, we were content. There was no fear or anxiety in our lives. Everything was simpler, purer. Now, I feel that has changed,” she says. To the little girls in the plaid dresses, fastened with safety pins in lieu of buttons, she would offer one piece of advice: enjoy as carefree a childhood as possible, because life becomes more challenging later.

Lamprini married, but her husband died young due to a heart condition. Raising their daughter demanded numerous sacrifices and strenuous work. “Conditions were not easy. All was burden, dust, and smoke. But we coped.” She has remained friends with the other two women in the photo, Maria and Helen. Helen lived in Germany for a few years but eventually returned to Ioannina. All three still live in Epirus. It was in 2007 when one of their daughters identified her mother in a magazine photo. “We were deeply moved. It was the sole photo from our childhood. Cameras were scarce then in our region, where even shoes were considered a luxury,” Lambrini recounts. In preparation for the exhibition that McCabe was organizing in the area, the three women reunited with him and posed together once more. “It was a special moment for all of us. A link to the past, to another era, and a way of life that is now utterly lost,” she says.

© Robert A. McCabe

The Hotel Where Schliemann Stayed

The hotel Belle Helene was built by Lula’s grandfather. A native of Northern Epirus, he departed his village, Drovia, at the age of 18 and journeyed for days on a donkey. In 1864, he settled in Mycenae, fell for the most beautiful woman in the village, and together they established a modest hotel. The name “Belle Helene” was suggested by the archaeologist Heinrich Schliemann, who resided there for prolonged periods over a decade, specifically in a first-floor room. “He saw it as his home. Once he departed, the room remained locked. It retained a special aura, and was the priciest,” says Lula, or Electra, as her father would call her – all his children had, in addition to their baptismal names, one taken from Greek mythology. A line from the Odyssey graces the hotel entrance sign: “Greetings, stranger, you are warmly welcomed by us here.”

When she was born, her father was already managing the hotel and marking the dawn of the tourism industry. “The entire village was at our service, ensuring proper accommodation for our guests. They supplied fresh produce such as eggs and meat, and lent their mules to our guests for transport,” she says. She can still recall the parties on the balconies, the tales about Agamemnon, and, most vividly, a six-door black Cadillac. Marrying at 17, she devoted herself to raising her children, but continued to assist her parents, particularly during summers. “As the years passed, groups of tourists began arriving, as did caravans. Residents continued to depend on tourism, selling postcards, souvenirs, and my husband worked as a cook.” However, over time, changes occurred. Large groups no longer lodged at the Belle Helene, instead favoring larger hotels nearby, with travel agencies claiming a portion of the profits from the tourists’ meals.

Over time, the small 19th-century stone building that houses the hotel fell into disrepair, although the Dasis family labored to maintain its appeal through stories of the past. “Fortunately, a nephew recently took over. It’s currently undergoing renovations, and it will be restored to its former glory,” Lula says with pride.

© Takis Tloupas

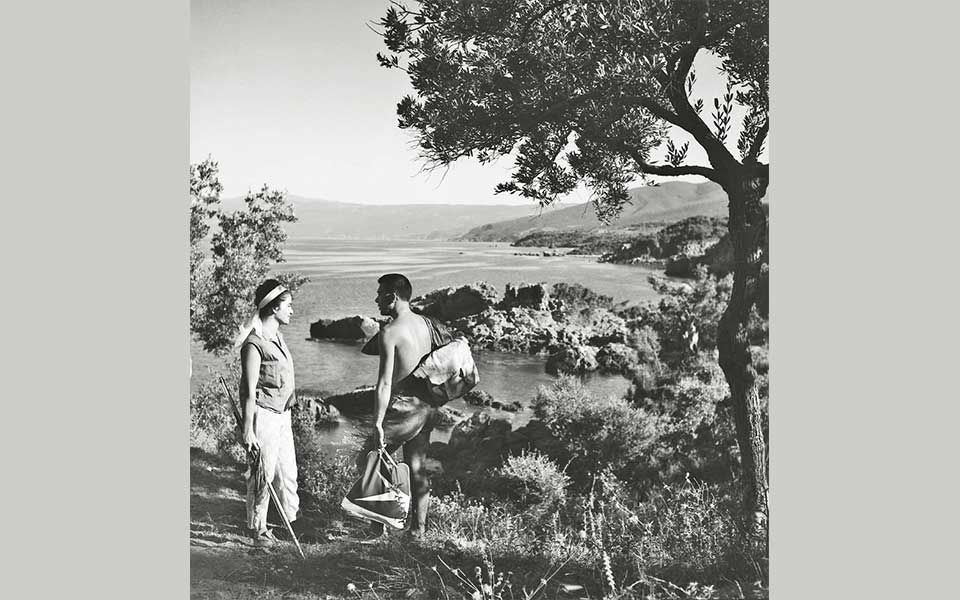

Agiokampos, 1963 – Content Just to See the Sky

Dimitris Managas first encountered Takis Tloupas in Larissa. Takis’ carpenter father would make young Dimitris spinning tops with which to play. In the late 1940s, when his good friend began photographing the Thessaly region in Central Greece, Dimitris joined him, even posing as a model. “We traveled to Mt Olympus, Mt Kissavos, surrounding villages, and soon all over Greece, initially by Vespa, later in Takis’s grey Citroen 2CV, a car that braved even half a meter of snow, chainless,” he says.

Dimitris watched Takis document post-war life in remote, forgotten parts of the country. “There were no roads, just a lot of dirt and mud. But that’s what he enjoyed: photographing and hearing stories and traditions of these hardworking, albeit uneducated, people who were kind, hospitable, and authentic.”

Later on, Tloupas’ lens captured Dimitris’ life with his wife Toula. They had met while she was a Red Cross volunteer, and married in 1957. The fact that her uncle was a political exile on Makronisos Island had hampered the family’s ability to find work, and Toula grew up without luxuries. Her parents did own a house and some land which they farmed, but times were difficult. “Nonetheless, even with little, we were content. Just stepping outside to pick fruit from our trees or lying down on the grass and gazing at the sky was enough,” recounts Toula.

Dimitris and Toula, along with Tloupas and his wife, continued to travel, and Tloupas continued to take photographs. These were years of change and hope. Dimitris, employed at a bank from the age of 18, eventually retired 40 years later as a bank director. Before retiring, however, they signed Toula’s house in Larissa to developers to provide their two daughters with apartments in Thessaloniki, where they themselves had relocated in 1972.

“Whenever I returned to Larissa, my first stop was at Takis’s house. One day, I found him in his studio, seated in an armchair. ‘I’m waiting for my turn,’ he told me. ‘Stop that, we have time,’ I said. Unbeknownst to me, he had started to fall ill. Do you know how hard it is to say farewell to your friends?” For the now 94-year-old Managas, his friend’s passing symbolized the end of an era.

This article was previously published in Greek at kathimerini.gr.