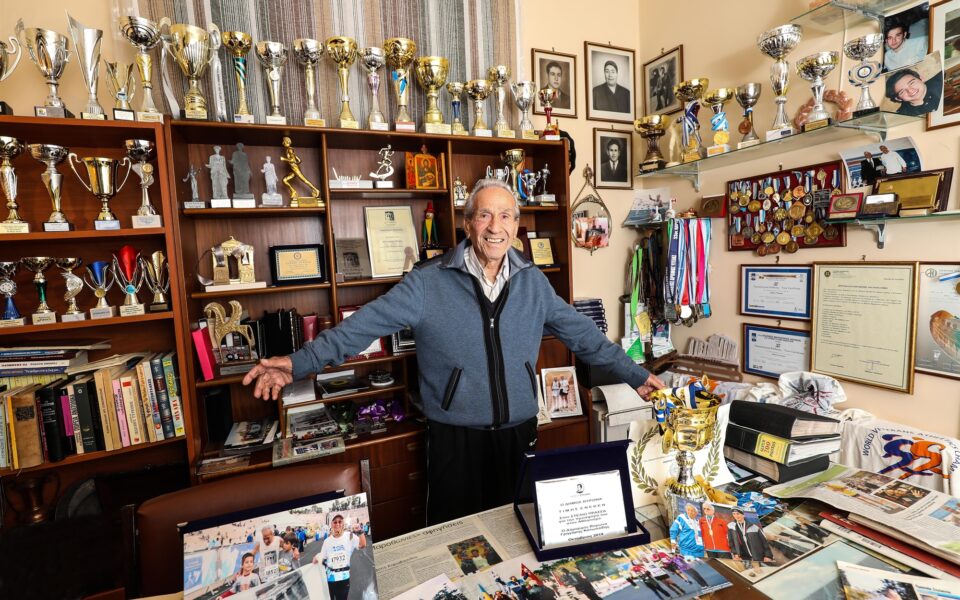

Ninety year-old Stelios Prassas, the oldest person to finish the Athens Marathon, discusses his philosophy for life and why he has no plans to stop running.

He used his olive grove as a track. Over the last two months, unable to practice in the local stadium as he didn’t have a car, Stelios Prassas ran up and down the field with its 96 olive trees and free-range chickens on the plain of Marathon. On this route, hemmed in by the surrounding hedge, with his shoulders raised and his quick stride, he met his training targets before recently becoming the oldest person to finish the Athens Marathon, aged 90. “If you work out a bit, everything gets better,” he says.

He remains in perpetual motion, despite it being only a few days after he completed the 42 kilometers and 195 meters of the Athens Marathon in eight hours. He tells us that on the day after the race he tried sprinting to the end of his field and felt fine. “An athletic lifestyle is tremendously healthy,” he says as he shows us around his house. Even when standing still, the slight incline of his body toward the ground and that sparkle in his eyes makes him look more like a sprinter who has been told to get ready. “This year was particularly nice as many participants came and told me, ‘We are going to finish this race,’ ‘We’re going to have fun.’ Everyone was talking from start to finish,” he states.

A veteran marathon runner, Stelios Prassas is the oldest person to finish the Athens Marathon, aged 90.

© Nikos Kokkalias

Those who had a quick chat with him while running the marathon were not the only people to approach him recently. Since the race, the experienced athlete has been in demand among journalists and reporters. The press is so interested that Prassas has had to jot down interviews for radio TV and other media on a piece of paper so he doesn’t forget. The man himself still finds this newfound fame curious. “I’ve completed the race before in better times,” he says disarmingly to Kathimerini. Indicatively, in 2018, when Prassas was 87, he finished the same race in six hours and 27 minutes.

In an era of smart watches, wearables and long-winded, self-promoting posts on social media, Prassas represents a different generation of runners. He broke in his shoes at the Panathenaic Stadium and on the dirt roads of Aghios Kosmas before running took off and became a popular pastime. He was there when there were no traffic regulations for even the biggest of races – unlike today with its ever-growing list of safety regulations – and when the participants ran alongside moving cars. Participation in those races numbered in the hundreds, and not the thousands we have come to expect every year in Athens.

Part of his medal collection for long-distance races from Greece and abroad.

© Nikos Kokkalias

A race for survival

Prassas was born in Athens on November 5, 1931. His father was a laborer. “A fighter, a good, hearty man. He did anything that was asked of him, to make ends meet and feed his family. In his 90s he went to the farmers’ market, bought some groceries, cooked a meal at home, lay down and he was gone. That suddenly, without even involving a doctor,” Prassas says, looking back.

He was not given the opportunity to complete his elementary school education as planned, interrupted by the Axis occupation of Greece. “After the war was over, we got a graduation certificate. What could we have learned? We didn’t learn anything,” he says. For 14 years he operated a lathe in central Athens, making pots and pans. But he has always had a passion for sports.

He played football, always as a striker, for several teams in Athens, including Niki Plakas and Arion Agiou Artemiou. He stopped playing when he was 27 to focus on his full-time job as a laborer and painter. He would later open a store in Vyronas that sold color paints, hardware and tools. He got married and had a son. “I was the only one who would close my store at 3 p.m. to pick up my son and go to Agios Kosmas to play football with our friends. I was obsessed with football, I loved it,” he says.

“Stylianos Prassas’ Trophy Room” - medals, certificates and trophies from dozens of marathons are all displayed in this room in his house.

© Nikos Kokkalias

Prassas’ sports card when he played soccer for Niki Plakas in 1951.

© Nikos Kokkalias

‘I am ancient’

However, Prassas has not had much coaching in his running career. “I never had a trainer,” he says. “I only do what my system tells me to, what my body and soul tell me.” Neither has he used equipment employed by other runners. He still runs wearing an old-fashioned timepiece and to this day finds it strange that other runners near him can see how much of the race they have completed and what their pace has been. “I hear them while they’re running, discussing what kilometer their watch tells them they are on. If somebody told me when I was born that it would be like this, I wouldn’t believe them. I have been left behind by technology,” he says. “I am ancient.”

Prassas’ approach to running is reminiscent of other older runners. In October 2016, 85-year-old Ed Whitlock finished the Toronto Marathon in three hours and 56 minutes, a record time for his age group. “He runs wearing 15-year-old shoes and a shirt that’s two or three decades old. He does not have a coach. He does not have a special diet. He does not record the number of his training kilometers. He does not keep track of his heart rate, use ice therapy, or receive massages. He shovels snow in the winter and takes care of his garden, but he does not lift weights or do crunches,” an article in the New York Times said of the Canadian long-distance runner, who died a year later of prostate cancer.

Football, his great love. First on the right, he played as a center forward in clubs in Athens.

Apart from his field, Prassas avoids non-track training, as he is concerned about accidents on worn and bumpy roads. He prefers the safety of a synthetic track, its smooth and predictable surface. “I get to the finishing line and run as much as I want. I tell myself today I will run five or 10 kilometers,” he says. He used to train more regularly but still employs some of the techniques used by distance runners, like carbo-loading – the frequent consumption of carbohydrates (usually pasta) – for at least three days prior to a race, to store as much glycogen as possible.

During the recent Athens Marathon, Prassas felt an ache in his lower back, which he no longer feels. In the days after, he spoke with orthopedic doctor Theodoros Papapolychroniou and told him of his race finish and will most likely visit him soon. Before his 80th birthday, Papapolychroniou had performed surgery on Prassas. The veteran distance runner had two complete hip replacements – a procedure used to counter serious cases of osteoarthritis.

After eight hours of herculean effort, Prassas finished the Athens Marathon again.

© InTime Sports

“These conditions can progress slowly, over 10 or 15 years, or rapidly as in Prassas’ case. Within a year the hip joints had deteriorated to the extent where walking was painful,” says the doctor. “When he came to my office, he was a man with a particularly strong desire to keep moving and walking, and the pain in his hip kept him from basic everyday activities, like going to the store or the supermarket or even standing up for a few hours. However, he has made a full recovery as his marathon times attest.”

After the successful surgeries and his rapid recovery, Prassas visited Papapolychroniou regularly. “He was in good condition, and we often joked about it, with him saying he was going to run a marathon and with me replying that he should look after himself,” the doctor says.

The 90-year-old marathon runner wants to continue running all over the world for as long as he is able. He stresses that he does not feel troubled in his daily life. He has lived through tough times, through “hunger and misfortune,” and is not afraid. “I am happy,” he says, “as long as I have my health and can remain on this earth, alive.”

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.