Thessaloniki’s prestigious International Documentary Festival is one of the best occasions to visit the city. The screening rooms are filled morning to night, and the downtown streets are alive with intellectual energy. With the last of the winter chill in the air, there’s no better time for loading up on documentaries day and night and recharging in between with a hit of Thessaloniki’s urban cool and famously great dining scene.

There are over 260 documentaries on this year’s program, including a wealth of Greek selections that offer rare insights into varied aspects of the Greek experience. There will be a number of rescreenings of historic documentaries of decades past; it’s a rare opportunity to get to know some of the most influential Greek filmmakers of earlier generations through groundbreaking works. These are just some of the 71 excellent Greek selections touching on a wide variety of themes. Most of these will be screened live, but others are part of the online festival (click here for more info).

The Greek Islands

Today, with mass tourism having taken hold on so many Greek islands and with sun and fun having usurped the narrative there, it’s wonderful to look back at the individual natures of the islands, and those aspects of their character that still remain unchanged. A host of works, some older works with historic footage and some contemporary films, bring unique perspectives on the traditions and histories of the islands.

A number of these films are by seminal filmmakers and document worlds that are now lost; the films themselves have become legends. Considered a precursor to the New Greek Cinema that would take hold after the Junta, Thirean Matins (1968) by Stavros Tornes (one of the festival’s screening rooms is named for him) and Kostas Sfikas is one of these. The film captures Santorini in 1967, with many of the impoverished inhabitants working the soil in their beautiful yet uncompromising landscape, even as the emerging tourist industry first takes hold. In the words of the directors: “Tragic, satirical, epic, lyrical elements had to be blended together within a musical frame completely divested of naturalism, acquiring a musical expression that stems from tradition while also being a present-day anti-metaphysical cry of suffering.”

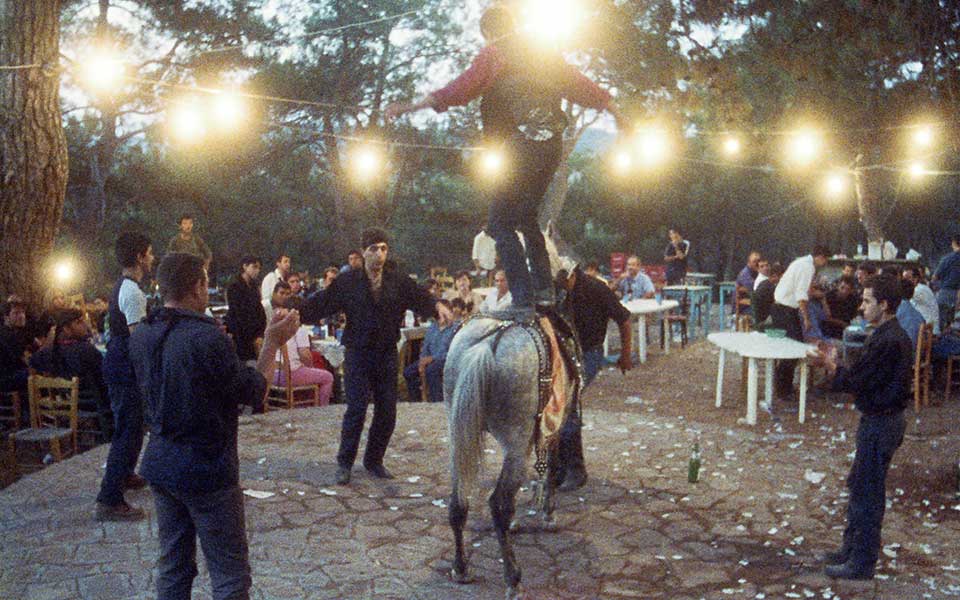

A decade earlier, Roivos Manthoulis had made a lyrical film about the Ionian island of Lefkada, home to both Aristotelis Valaoritis and Angelos Sikelianos. This work, Leucada, the Island of the Poets (1958), offers images of an island still free of tourism. Takis Kanellopoulos’ Thassos (1961) takes an ethnographic approach to another island that was then still largely untouched, focusing on Thassos’ spirit and its way of life, unchanged for generations. Pantelis Voulgaris takes us to the island of Skyros in the Sporades and the Dionysian ecstasy of The Goat Dance – although the island’s way of life has changed through the decades, the custom seen in this 1971 film is still part of the island’s culture.

The Dance of the Horses (2001) by Christos Voupouras transports us to Lesvos to learn the tale of another ritual that unites various threads of a complex identity. Michael Roubis captures an unusual life on Crete in Takis (2025), the story of a former nightclub owner who now devotes his energy to sheltering the stray and abandoned dogs of Crete, inspiring global support and changing local attitudes as he creates a home for 400 dogs.

In contrast, Manos Efstratiadis’ In Mytiline (1973) shows a way of life already altered. Shot in the early 1970s and free of dialogue, the film serves as a wry critique of the aesthetics and social behavior shaped by the Junta’s “Homeland-Religion-Family” doctrine. A post-Junta Greece in transition, as a shift in social mores takes hold, is captured in Matheo Yamalakis’ On a Little Greek Island, shot on Ios in 1976. Nowhere have the seismic social and economic changes of tourism been felt more dramatically than on Mykonos. Steve Krikri’s Super Paradise (2024) shares the many identities and divergent experiences – from its carefree, inclusive past to its exclusively luxurious present – that have unfolded over the last half century.

Greece’s Agricultural and Industrial Heritage

Many selections at this year’s festival look at aspects of Greece rarely considered by visitors but often intrinsically tied to regional identity. Megara (1974) straddles the agricultural, the industrial, and the political; in what is considered one of the most important Greek documentaries of the past fifty years, Sakis Maniatis and Yorgos Tsemberopoulos share the story of the inhabitants of Megara as they try to protect their farmland from the Junta, who want to build an oil refinery there.

Tobacco, a definitive crop that shaped not just the economy but the culture of Macedonia and Thrace for generations, is at the heart of Gazoros Serron (1974), Takis Hatzopoulos lets the hard lives of the tobacco workers in this small village of Serres tell their own tale. Soon after finishing this, the director would join with Lakis Papastathis to introduce Paraskinio (“Backstage”), a groundbreaking documentary series for Greek television.

The Charcoal Makers of Ikaria Island (2024) by Manos Arvanitakis shares lesser-known stories from this island so famous for being part of the Blue Zone. Another recent film, Yorgos Kyvernitis’ Tonnage (2024) looks at the work culture of the dock workers at the port of Eleusis. The Aluminum of Greece Corporation commissioned Roussos Koundouros to make an industrial documentary detailing the production of aluminum (and the construction of the industrial infrastructure required to achieve that) at Aspropyrgos in Boeotia. The resulting short film Aluminum of Greece (1965), set to an electronic score, is unexpectedly poetic.

Looking at the Mainland

Two other historic films of Takis Kanellopoulos – director of the aforementioned work Thassos – are valuable documents of both a way of life lost to time and of his pioneering approach to ethnography and filmmaking. With the poetic Macedonian Wedding (1960), he arrived on the scene to instant acclaim. Kastoria (1969), only very recently recovered, constitutes the third film of his Macedonian Trilogy. The three short films will be screened together. The moving Prespes (1966), by Takis Hatzopoulos, will be screened together with his later work Gazoros Serron. In Fire Walkers of Greece (1959), Roussos Kountouros unites ethnography and documentation, sharing the world of the Anastanarides through the words of the poet Nikos Gatsos. It will be screened with The Goat Dance and Aluminum of Greece.

The Political Landscape

In the eventful 20th century, Greece experienced the Balkan Wars; the population exchange following defeat in Asia Minor; two world wars; the Civil War; and two dictatorships. People who experienced and participated in many of these events first-hand speak to us in insightful documentaries that view the political through a personal lens. A Civil War guerilla fighter (and subsequently a political prisoner for two decades) speaks to us in Alexandros Papathanasiou’s White Mountains (2024). Till Our Dying Breath (2024) by Manolis Sfakianakis takes us back earlier, using the Memoirs of Callinicus Kritovoulides to tell the story of the Cretan’s struggle for freedom and ultimate union with Greece.

In The Land of Traumas (2024), Anastasios Stamnas shares the work of Anna Vidali, who looked at the experiences of women who lived through the resistance and the Civil War, as well as her own experiences. Women Fighters – 2nd Part 1944-1960 (2025), by Leonidas Vardaros, looks at the events of the mid 20th century through PEOPEF – the organization of families of political exiles and political prisoners. In Lost Yanninina: A Topography of Jewish Memory (2024), Nikos Chrisikakis shares testimonies, collected from 2009-2024, of the city’s Holocaust survivors and looks at the places that still hold memories of this terrible time.

The poet and journalist Katie Drossou, active in the resistance during WWII, was entwined with the events of that war, the Civil War, and the large-scale exiles that followed. It’s felt in her work, and shared in Kaiti Drosou: Memory Box (2024), by Athanasia Drakopoulou. In Lo (2025) director Thanasis Vassiliou shares his family history and memories of the Junta from his now empty childhood apartment in Athens.

Films on Art

The history of Greek Cinema cannot be told without the art of Vakirtzis: in the 1950s and 1960s, his gigantic hand-painted posters advertised new films. Combining pop and expressionist sensibilities, an incorporation of graphics, and an innate sense of story-telling, they’re fascinating social documents and splendid works of art. What’s more, there were a lot of them – today, over 50 framed reproductions of Vakirtzis’ works line the stairwells of the Olympion Cinema, the festival’s flagship venue – hence the title A River Called Vakirtzis (2024) by Panos A. Thomaidis.

Eva Stefani’s Bull’s Heart (2025) follows choreographer Dimitris Papaioannou’s dance piece Transverse Orientation through rehearsals and performances. L’éclairage revient / Waves of Light (2025), by Pantelis Kalogerakis, Michalis Kalogerakis and Panagiotis Andrianos, documents a collaboration of the Greek National Opera with the Public Power Corporation, in which five power plants hosted site-specific video performances with scripts and music inspired by the unique spaces, their histories, and the people who worked in them.

How to Make the Most of the Festival

The screening rooms of the festival are within easy walking distance of one another, with two in the main building – the Olympion Cinema, a landmark on Aristotle Square. For information and tickets, visit the glass box in the middle of the plaza, directly in front of the cinema. Other screening rooms are less than five minutes away, at the port. The self-service café on the 5th floor of the Olympion has a great view and inexpensive coffees, which are also available to go if you’re dashing to a screening. And don’t be put off by the idea of catching a film at noon – throughout the festival, the mood is high at all hours and you may want an early start to a full day. If you find yourself with a free time slot, check the screening schedule to see if there’s something interesting.

The official site for the TIDF is here, and the program for the festival is online here. You can browse through categories such as International Competition; Open Horizons; AI: An Inevitable Intelligence; and Geography of the Gaze: Off-Plan Greece (1950-2000). There’s a link to buy tickets (there’s a small surcharge) for each film; note that you can switch the language by clicking on the globe at the top. Tickets are €5 each, or a packet of 10 for €35. Longer films are screened on their own, while several shorter films may be screened together. Popular films sell out in advance. If you really want to see a sold-out film, show up anyway – there may be an additional line at the door to fill the seats of those who don’t show up.

The Thessaloniki Cinema Museum is among the screening rooms in the port and offers a thorough, creative and English-friendly introduction to the history of Greek cinema with lots of clips. Remember, too, that Thessaloniki is a famously great town for food – at this link, the city’s most interesting chefs share their own favorite spots.