From traditional barrel-making to age-old folk dances, seven new entries on Greece’s National Inventory preserve the country’s living heritage for future generations.

Greece’s cultural heritage is more than just ancient temples and museum artifacts – it thrives in the traditions, crafts, and customs passed down through generations. From the rhythmic steps of folk dances to the intricate techniques of master artisans, these living traditions are woven into everyday life, shaping identities, and strengthening community bonds.

Now, seven more traditions have been officially recognized as part of Greece’s National Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage, a growing collection dedicated to safeguarding the country’s diverse cultural expressions. This recognition aligns with UNESCO’s 2003 Convention for the Safeguarding of Intangible Cultural Heritage, reinforcing Greece’s commitment to preserving the customs, dances, crafts, and social practices that define its people.

Culture Minister Lina Mendoni, upon accepting the recommendation from the National Scientific Committee, emphasized that these newly registered elements are not just remnants of the past but vibrant traditions that continue to evolve.

“Intangible cultural heritage is the soul of our culture. It consists of the songs, dances, customs, techniques, and knowledge passed down from generation to generation, building bridges between the past, present, and future,” Mendoni stated.

From the art of barrel-making in Achaia to a centuries-old funerary tradition in Attica, here’s a closer look at the seven customs now safeguarded as part of Greece’s cultural legacy.

Wine barrels at Achaia Clauss winery in the northwest Peloponnese.

© Shutterstock

The Craft of Barrel-Making at Achaia Clauss

Nestled in the rolling hills of Patras, in the northwest Peloponnese, stands Achaia Clauss, one of Greece’s most historic wineries. Established in 1861 by Bavarian entrepreneur Gustav Clauss, it is best known for its signature Mavrodaphne wine – a deep, sweet red that has become synonymous with Greek winemaking.

But beyond its vineyards, Achaia Clauss preserves another rare craft: the art of barrel-making. Master coopers, using techniques passed down through generations, handcraft oak barrels that have been integral to the winery’s production for over 150 years. The precise shaping, assembling, and charring of these barrels influence the wine’s flavor, making this tradition an essential part of the region’s viticultural identity.

Remarkably, some of these barrels date back to 1882 and are still in use today. To honor this heritage, the “Varelatiko” (Barrel) Museum was established on-site, offering visitors an in-depth look at the meticulous craftsmanship that continues to define Achaia Clauss.

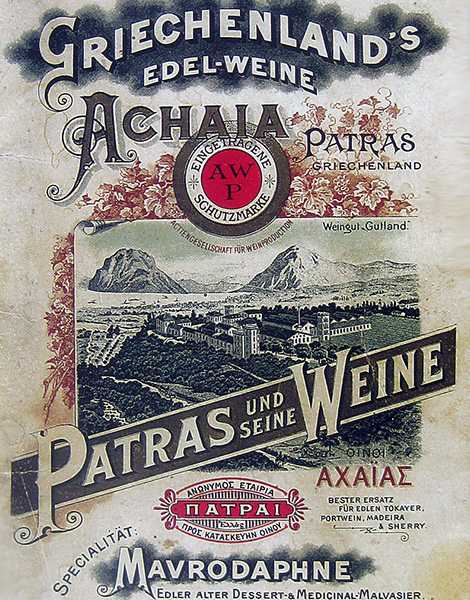

An old German advertising poster for Mavrodaphne wine from Patras

Sweet and rich in flavor, Mavrodaphne undergoes a special winemaking process.

The Viticultural Tradition of Mavrodaphne at Achaia Clauss

While barrel-making plays a crucial role, Mavrodaphne wine itself has become emblematic of Greece’s viticultural heritage. Made from a black grape indigenous to Achaia, this unique variety – whose name means “black laurel” (some say it was named after a woman called Daphne) – undergoes a special winemaking process. Fermentation is halted with alcohol, preserving the grapes’ natural sweetness and creating its distinctive rich flavor.

Beyond its role in festive gatherings, Mavrodaphne holds deep religious significance. It is commonly used as nāmā, the sacramental wine of the Holy Eucharist in Greek Orthodox tradition, further strengthening its cultural and spiritual ties to this corner of the Peloponnese.

The century-old burial Custom of Sourmena, in southern Attica.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

The Funerary Custom of Pontians in Sourmena, Attica

In Sourmena, south of Athens, the Pontian Greek community observes a deeply symbolic funerary tradition, blending remembrance with celebration. Each year, on the first Sunday after Greek Orthodox Easter, families gather at the Church of the Transfiguration for a communal liturgy before proceeding to the local cemetery.

Here, the atmosphere is not one of sorrow, but of connection. Families stand by the graves of their ancestors, sharing prayers, stories, and symbolic foods such as Easter eggs and tsoureki (sweet bread). These offerings honor the departed and reinforce the link between past and present.

For Pontian Greeks – ethnic Greeks from the Black Sea region who were persecuted and forcibly exiled in the early 20th century – mourning is a communal act. It is not just about remembering the dead but celebrating their lives and strengthening intergenerational bonds.

Tsipouradika have become cornerstones of social life in Volos and Nea Ionia.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

A selection of "mezes" (appetizers) are commonly served alongside the tsipouro.

© Angelos Giotopoulos

Tsipouradika in Volos and Nea Ionia, Magnesia

If you’ve ever wandered through Volos or Nea Ionia in southeastern Thessaly, chances are you’ve come across a “tsipouradiko” – a small tavern where locals gather to enjoy tsipouro, a strong, grape-based spirit, served alongside an ever-changing selection of “meze” (appetizers).

But these eateries are more than just places to eat and drink. Tsipouradika follow a unique, unwritten set of social customs: each round of tsipouro is accompanied by a different assortment of meze, and seasoned patrons know exactly what to expect with each pour.

With a history stretching back over a century, these taverns have become social institutions, where friendships are formed, business is discussed, and stories flow as freely as the drinks.

Mourning the end of harvest season - the Lēidinos Custom of Aegina.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

The Lēidinos Custom of Aegina

Every year on September 14, in the village of Kypseli on the island of Aegina, locals partake in one of Greece’s most unusual customs – a mock funeral marking the end of the harvest season. Known as Lēidinos, this theatrical event symbolizes the close of summer labor and the transition to quieter winter months.

The word Lēidinos refers to a light meal traditionally eaten by farmers at dusk during the working season, from mid-March to mid-September.

The event unfolds as a parody funeral, complete with mock lamentations, a ceremonial burial, and a feast featuring barley buns and “kollyva” – a wheat-based dish typically associated with mourning. But instead of grief, the gathering ends in music, dance, and festivity, celebrating the cycle of renewal and change.

The Trata Dance

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

The Trata Dance in Perachora and Loutraki, Corinthia

At the climax of Carnival season, the towns of Perachora and Loutraki in northeastern Peloponnese come alive with the “Trata,” a ritual dance believed to have roots in ancient passage rites.

Dancers move in a crisscross pattern around a fire while singing call-and-response (“antiphony”) folk songs in both Greek and Arvanitic dialects. Performed in church courtyards and village squares on Clean Monday (the first day of Lent), this ritual represents community unity, renewal, and transition into the new season.

The newly-revived Saint George Custom in Karditsa.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

The Saint George Custom in Mitropoli, Karditsa

Each year, on Saint George’s feast day, the village of Mitropoli (Paliokastro) in western Thessaly revives a nearly lost tradition. After the Divine Liturgy, local women gather in the church courtyard to perform an “a cappella” – a song without instrumental accompaniment – dedicated to Saint George.

Sung in antiphony, where one group sings a phrase and the other responds, this sacred custom had almost disappeared by the 1990s. However, in 2015, it was revived through the efforts of the local Board of Directors and the women of the Cultural Association of Mitropoli.

With these seven newly recognized traditions, Greece continues to celebrate and preserve the intangible elements of its cultural identity – keeping them alive for future generations.