I imagine a Mycenaean craftsman in the ancient city of Ialysus on Rhodes in 1200 BC, bent over his anvil with tools of bronze and ivory trying to etch two sphinxes on the tiny surface of a gold seal ring. Dozens of studies in wax and wood must have preceded this incredibly challenging process. No one can say whether this unnamed craftsman was a free man or a slave, but we do know that the beautiful ring he created ended up in the tomb of someone important, probably a man, and that it was regarded as a status symbol that would accompany the deceased on his journey into eternity. Instead of staying buried in the dark, however, the ring traveled through the ages and from south to north, from ancient Rhodes to modern-day Sweden.

What a marvel, some 3,200 years after its creation, to see this delicate ring laying in a small white box on a massive oak table at the Nobel Foundation in Stockholm, beneath a portrait of the foundation’s visionary founder, Alfred Nobel. Just a few hours later, it was placed in the hands of a representative of the Greek Ministry of Culture and embarked on the return journey to Rhodes, where it will go on permanent display.

But how did it end up at Stockholm’s Museum of Mediterranean and Near Eastern Antiquities and under the ownership of the Nobel Foundation?

The ring stayed buried until 1927, when it was brought to light by the director of the Italian Archaeological School at the time, Giulio Jacopi, during excavations of the Mycenaean necropolis of Ialysus. The ring was among dozens of finds made in a vaulted tomb that had been assigned the number 61.

In 1933, meanwhile, the school’s annual report contained drawings, photographs and descriptions of all the finds made at the site, including the ring, thus providing irrefutable evidence of its existence and its authenticity. A few years later, in 1940, some of the more valuable artifacts were taken from the Dodecanese island for an exhibition on the “Italian colonies” in Naples, and there they stayed until many were returned after the end of World War II thanks to the efforts of renowned archaeology professor Spyridon Marinatos. The ring, however, was not among them.

There is some evidence to suggest that one of the people working for the Italian School on Rhodes during the war was involved in the disappearance of several boxes containing gold finds. No one can be absolutely certain of the person’s identity, though there was one staff member who came under suspicion after Greece was liberated from the Nazis. From 1940 to 1975, all trace of the ring seemed to have disappeared, until the curator of antiquities for the islands of the Dodecanese, Christos Doumas, received a letter from Swedish friend and colleague Carl-Gustaf Styrenius, who had spent several years at the Swedish Institute at Athens and knew a lot about the Mycenaean civilization. He was asking for information on the authenticity of a ring that was on display in Stockholm and looked much like the one found decades earlier on Rhodes. Doumas responded that it probably was the real thing, but the matter did not go any further.

The fate of the ring was brought back to the fore recently by the Greek Ministry of Culture’s active Directorate for the Documentation and Protection of Cultural Property (DTPPA), which dug up the correspondence between the two and prioritized the case.

The Greek authorities were well positioned to claim the ring and their Swedish counterparts tracked down Styrenius, now aged 93, and were able to confirm his correspondence with Doumas. The Greek investigation also discovered that the ring had been donated to the Nobel Foundation by Hungarian biophysicist and laureate Georg von Bekesy, who left a number of ancient artifacts to the foundation, many of which were fakes. It is believed that he probably bought the ring in the United States, where he lived, casting even more doubt on its authenticity.

Two experts – the curator at the National Archaeological Museum’s Department of Prehistoric Antiquities, Eleni Konstantinidi, and ancient art restorer Maria Kontaki, who specializes in metal items – were dispatched by the Culture Ministry to Stockholm to examine the Mycenaean seal ring and vouch for its authenticity.

But it took a lot more work for Greece to get its happy ending, because the Culture Ministry may be responsible for submitting the official claims for items to be returned, but it often comes down to the Greek embassies in the countries in question to take care of the politics. In this case, Ambassador Andreas Fryganas and diplomat Despina Poulou, who is responsible for cultural affairs at the Greek Embassy in Stockholm, made sure that everything was done properly and were responsible for getting the report containing all the evidence backing the ministry’s claim to the right quarters.

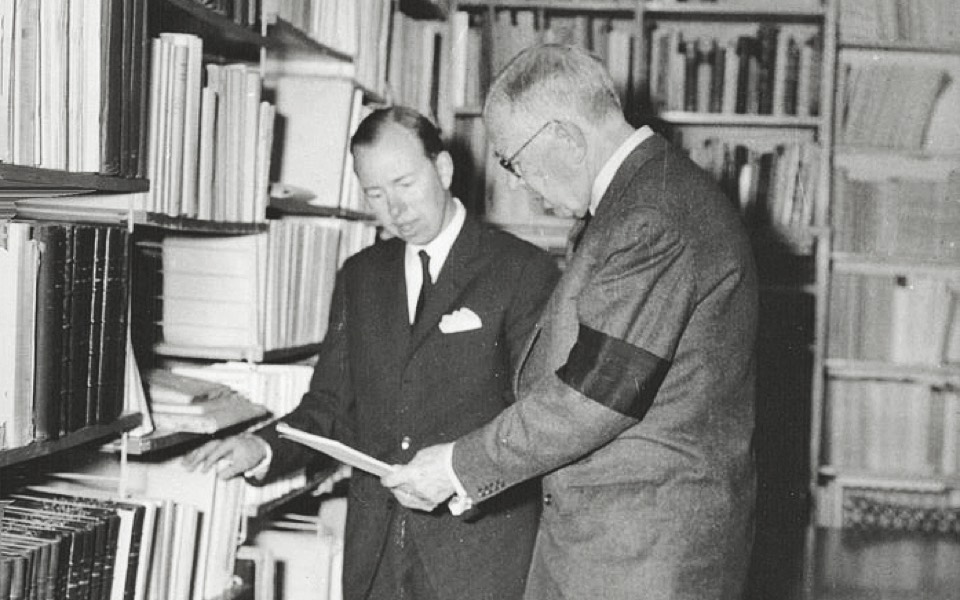

The handover ceremony took place on May 19, with the executive director of the Nobel Foundation, Vidar Helgesen, giving a speech that demonstrated not just how willing the Swedes were to cooperate, but also the changing tide in matters relating to cultural property.

“I asked my youngest daughter a couple of years ago where she wanted to go on holiday, and she said Greece. We visited the Acropolis and I told her about how the Parthenon Marbles ended up in London. She became angry and upset. Today, after handing over the ring, I can go home with my head held high,” he said.

Important moves

The Directorate for the Documentation and Protection of Cultural Property (DTPPA) was established in 2008 and started work in 2009, and has been instrumental in identifying, locating and documenting claims for the return of Greek artifacts residing abroad.

The Nobel Foundation’s generous response to the Greek claim comes in the wake of the exceptionally important gesture by the regional government of Sicily and the Italian state to return a fragment of the Parthenon frieze that had been on display at the Antonino Salinas Regional Archeological Museum in Palermo. Both moves are indicative of a new attitude among museums and institutions, but also the rejection of colonialist mentalities.

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.