The 40-year campaign for the return of the Parthenon Marbles, the world’s longest running cultural dispute, may finally be coming to a successful conclusion, according to a recent report by the Greek daily newspaper Ta Nea.

“Behind-the-scenes meetings” have been taking place over the last 13 months between Greek Prime Minister Kyriakos Mitsotakis and George Osborne, the current chair of the British Museum, regarding the fate of the 2,500-year-old sculptures, the report states.

Initial contact was made in mid-November 2021, during the Greek premier’s first official visit to the UK to discuss bilateral relations with his then British counterpart, Boris Johnson. During the meeting at No 10, Johnson rebuffed Mitsotakis’ request for the sculptures to be repatriated to Greece, but, according to the report, “exploratory talks” with Osborne later took place at the Mayfair residence of the Greek ambassador to the UK.

Since November 2021, Osborne has met with two senior Greek officials, including Foreign Minister Nikos Denidas and State Minister Giorgos Gerapetritis, either in person or remotely, to continue the negotiations and seek a “win-win solution” for Britain and Greece.

George Osborne, who served as the UK Chancellor of the Exchequer from 2010 to 2016, was appointed as chair of the British Museum in October 2021. Since then, he has made it clear that “there is a deal to be done” over the sculptures, removed from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin in the early 19th century, when Greece was still under Ottoman rule, and later sold to the British government in 1816.

Osborne’s meetings with the Greek PM and senior ministers, which have been kept away from the public eye, are being described by insiders as “not only credible but very exciting.”

In response to the article, The Guardian reported that the negotiations signal a “tectonic shift” in resolving the long-standing dispute.

© Shutterstock

During Mitsotakis’ return visit to London last week, he once again secretly met with Osborne, this time at the exclusive Berkeley hotel in Knightsbridge, prior to meeting King Charles III at Windsor Castle.

Speaking to the Greek newspaper, an official said: “the discussion went well. We’ve come a long way. However, some matters remain pending. We agree on a lot, but there are also points of disagreement.” Another Greek source close to the negotiations added: “The devil is in the details. An agreement is 90 percent complete, but a critical 10 percent remains unresolved. It’s hard to get there, but it’s not impossible.”

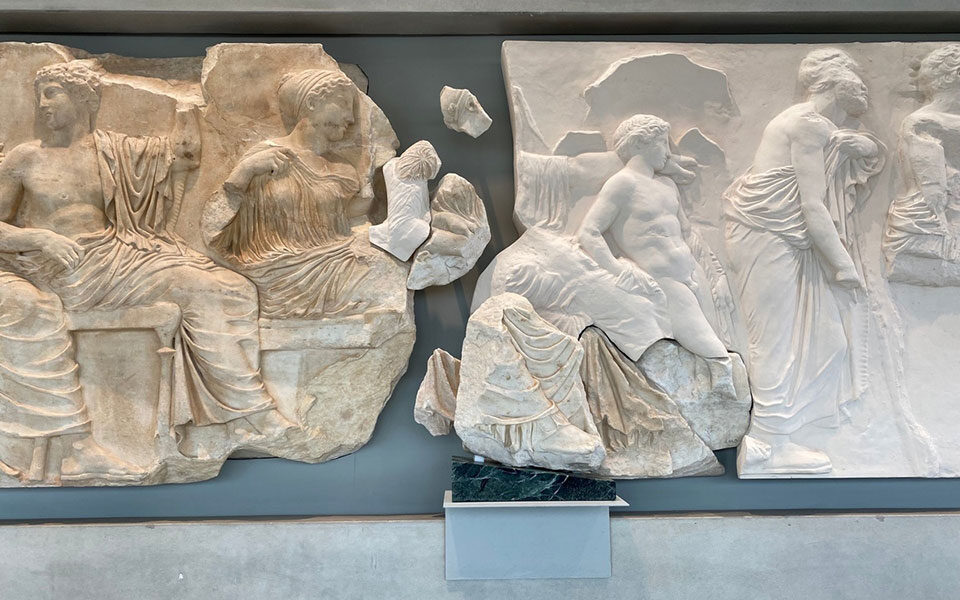

One major sticking point for the reunification campaign is the issue of ownership. The British Museum has always asserted legal ownership of the 5th century BC sculptures, where they have been on display since 1817. Greece, however, which became an independent, internationally recognized sovereign state in 1832, maintains otherwise. Under Greek law, all antiquities belong to the state. Past negotiations on this issue have quickly broken down, with the current Greek Minister of Culture, Lina Mendoni, describing Elgin’s removal of the sculptures, including 75m of the Parthenon’s original 160m-long frieze, “a blatant act of serial theft.”

Furthermore, the British Museum is prevented by law from “deaccessioning” objects in its collection. For that to happen, a change is needed at the governmental level, including an amendment of the British Museum Act of 1963, giving trustees more power to return artifacts to their places of origin.

Nevertheless, there is unprecedented momentum in favor of returning the Parthenon sculptures to Greece, as seen in the most recent opinion polls. Nearly 60 percent of Britons believe they “belong to Greece.”

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

According to the report, one solution under consideration is the so-called “Palermo model,” following the long-term loan and subsequent return of the “Fagan fragment” earlier this year from the Antonio Salinas Archaeological Museum in Sicily. In which case, a “partial return” of the sculptures from the British Museum could open a pathway to their eventual repatriation.

Another solution is a “long-term partnership” between the British Museum and the Acropolis Museum in Athens. In return for the Parthenon sculptures, Greece could lend the British Museum rotating exhibitions of other rare treasures for display in the Duveen Gallery, never seen before outside of the country.

In a recent interview for Greece Is, Christiane Tytgat, current chair of the International Association for the Reunification of the Parthenon Sculptures (IARPS), said: “Every museum curator is under pressure to present new things to the public all the time, and with ever diminishing funds, it is becoming impossible for museums to buy new things for their collections. If you establish close working partnerships with other museums, in this case the Acropolis Museum, you open-up the possibility of exchanging objects on long-term loans for temporary exhibitions. That for me is the solution. Send back the Parthenon sculptures to Athens and get a revolving door of other Greek antiquities to exhibit to the public.”

As the negotiations continue in earnest, both sides are striving hard to ameliorate the increasingly toxic atmosphere that has arisen in recent years, sensitive of each other’s “red lines.”

In The Guardian, Nikos Stampolidis, current director of the Acropolis Museum, gave this positive assessment of the talks: “If there were a solution, Britain could be the protagonists of an ethical empire because this transcends our countries. If the marbles were reunited here in Athens, within view of the greatest symbol of democracy, it would be a great act for humanity.”