In a public statement last week, the National Museum of Denmark announced that it will be keeping three sculptural fragments from the 2,500-year-old Parthenon, currently on display in its permanent collection in Copenhagen. The three fragments, consisting of two marble heads and a horse’s hoof, came to Denmark between 1688 and 1835.

Despite repeated calls by Greek authorities for the return of all surviving sculptural fragments of the Parthenon’s sculptures held in foreign institutions, Dr. Rane Willerslev, the Danish museum’s director, claimed that “after careful consideration, [the fragments] are of greater importance to the National Museum than if they were sent to Greece.”

While the majority of surviving fragments remain divided between Athens and London, the National Museum’s Head of Research, Dr. Christian Sune Pedersen, added that the three fragments on display in Copenhagen are of “great importance for Danish cultural history and for understanding our interaction with the world around us at a time when democracy was taking shape.”

“It is important for Danes to know Denmark’s place in European history. There have always been interactions between countries, and this has had a huge cultural impact on who we are today. The National Museum of Denmark owns a very small part of the total preserved sculpture fragments of the Parthenon Temple, which are of great importance for understanding our own history in the world,” the historian continued.

© Shutterstock

Much of the focus in the high-profile campaign to reunite the Parthenon’s sculptures in Athens has been concentrated on the large collection of dismembered sculptures in London, exhibited in the British Museum since 1817. With the support of UNESCO and other international heritage organizations, as well as growing calls from media outlets and independent pressure groups around the world, the trustees of the British Museum are under mounting pressure to return the so-called “Elgin Marbles” to Greece, abducted from the ancient temple by Thomas Bruce, the 7th Earl of Elgin, in the first years of the 19th century.

In recent years, fragments of the Parthenon’s decorative sculptures held in other museum collections have been steadily returning to Greece and put on display in the purpose-built Acropolis Museum in Athens, which opened in 2009. Among these have been the “Fagan fragment,” a piece depicting the foot of the goddess Artemis from the East Frieze, returned from the Antonio Salinas Museum in Palermo, Sicily, in 2022, and three fragments kept by the Vatican Museums in early 2023.

© Acropolis Museum

The Three Fragments in Denmark

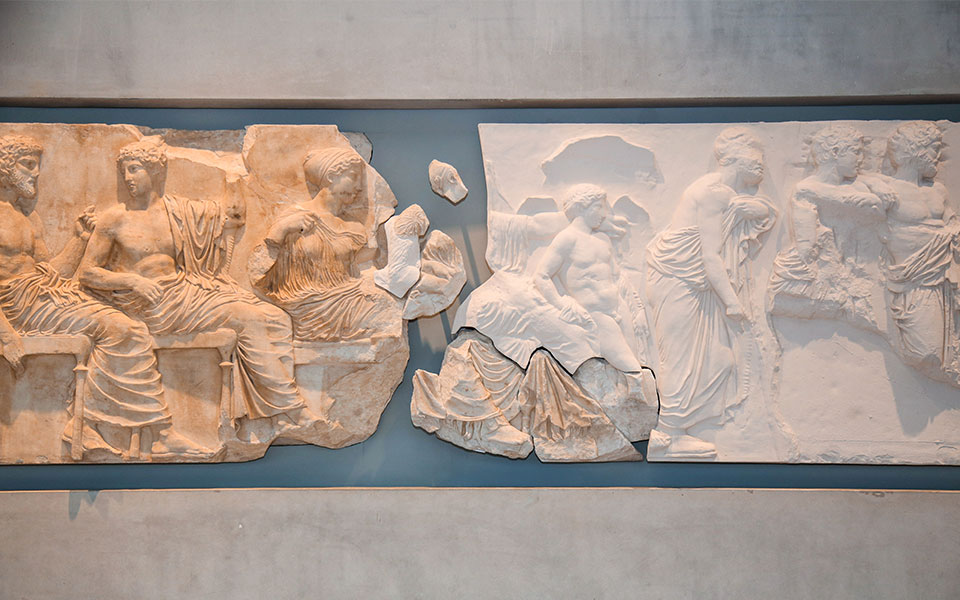

The three sculptural fragments on display in the Greco-Roman galleries of the National Museum of Denmark consist of two marble heads and a horse’s hoof, all from Metope IV on the south side of the Parthenon. This particular metope, forcibly detached from the Parthenon by Lord Elgin’s associates in the early 19th century, is one of 15 currently held by the British Museum.

The South Metopes depict scenes from the “Centauromachy,” a mythical battle between the Lapiths, a legendary tribe from Thessaly, and the half-human, half-equine Centaurs. The battle is symbolic of the struggle between the forces of order and civilization, represented by the Greek Lapiths, and chaos and barbarism, embodied by the Centaurs.

The two severed heads, displayed in two solitary cabinets in Copenhagen, depict a bearded Centaur and a more youthful, beardless Lapith. In the metope, the two figures can be seen locked in mortal combat: the Centaur, with upraised arms, hurling a large jug (hydria) at the kneeling Lapith, who is trying to defend himself with a shield. Both were brought to Denmark in 1688 by a Danish naval officer, Moritz Hartmann, who served in the Venetian army under the command of Francesco Morosini (1619-1694).

Morosini, who went on to become Doge of Venice from 1688 to his death, laid siege to the Acropolis of Athens in 1687, at the time occupied by the Ottoman Turks. During the lengthy siege, a Venetian mortar round, fired from the nearby Hill of Philopappos, blew up the magazine held inside the Parthenon, destroying the roof and much of the building’s south side. It is said that Hartmann purchased the recovered marbles, dislodged from the Parthenon in the explosion, from a street seller, and brought them back to Copenhagen.

The third fragment, which depicts the hoof of the Centaur, was brought to Denmark in 1835, the period immediately after the establishment of the modern Greek state. The fragment, which was broken in three and later repaired, was purchased by Christian Tuxen Falbe, Danish Consul General at the time, who was appointed by the Prince Christian of Denmark (the future King Christian VIII) to collect antiquities for the royal collections.

Today, the three fragments are on display in the Prince’s Palace in Copenhagen, the main building of the National Museum of Denmark, founded in 1807.

© Shutterstock

Mounting Pressure

Over the years, there have been repeated requests for the return of the three fragments held in the National Museum of Denmark, including a passionate plea by Georgios Fotopoulos, the then cultural attaché at the Greek Embassy in Copenhagen, in 2003:

“The two Copenhagen heads are of great symbolic significance for the Greek people, they are part of an entity, they belong with the rest of the Parthenon sculptures. It would be a splendid gesture on the part of Denmark to offer to return them … Regardless of when or how Denmark got them, the two heads belong in Greece.”

Support for the reunification of the Parthenon sculptures has been steadily growing in recent years, as successive Greek governments, spearheaded by the country’s Ministry of Culture, tirelessly campaign for their return from foreign collections. Opinion polls, including those in the United Kingdom, show overwhelming support for their return, with many campaigners arguing that it presents a golden opportunity to correct an historic wrong.

It is estimated that only around half of the Parthenon’s 2,500-year-old decorative sculptures are still in existence. Most of the surviving sculptures from the temple’s frieze, metopes, and pediments are now in more-or-less equal parts in the Acropolis Museum in Athens and the British Museum in London, and an estimated five percent remains in other European collections.