A New and Exotic Visitor at the Acropolis…

Michael Rakowitz’s acclaimed “Lamassu of Nineveh…

© teloglion.gr

Did you find the tunnel leading into the artist’s mind?” I ask Alexandra Goulaki-Voutyra before we set off on our exclusive tour of the fascinating retrospective exhibition on sculptor Yannoulis Chalepas (1851-1938) at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki’s Teloglion Foundation in cooperation with Onassis Culture.

It was a day after the opening weekend, which drew more than 450 visitors – a sound indication of the growing resonance of an artist who until recently was known mainly for the “Sleeping Maiden” tombstone at Athens’ First Cemetery. This is something that has started to change as a result of efforts to cast more light on the sculptor, key among which is a series of initiatives by the Onassis Foundation.

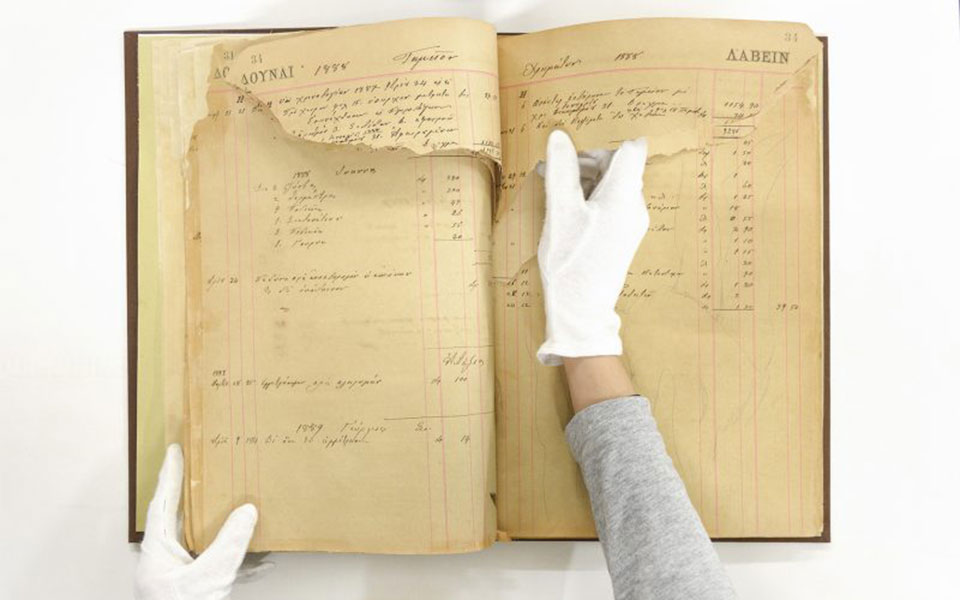

“After years of studying his drawings on single sheets of paper or the cloth-bound accounting books of his family’s marble cutting business, I feel that I have some sense of what this great artist was trying to do. He was a sculptor who committed every thought to paper, on every facet and every detail of a piece. He studied his concept facet by facet, at a time when he had no other tools at his disposal except memory and his talent for designing,” says Voutyra, director of the Teloglion, explaining a fundamental part of the exhibition, which consists of Chalepas’ drawings and notes on many of his pieces, including some of his most emblematic works.

© teloglion.gr

© teloglion.gr

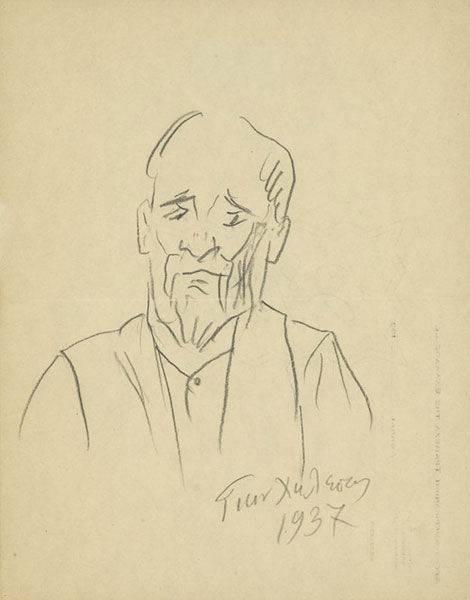

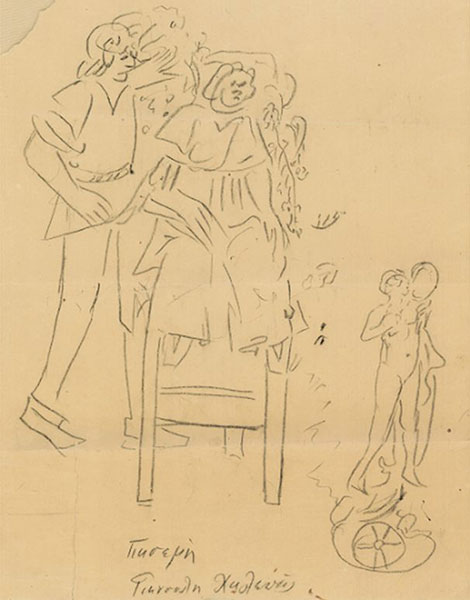

“He constructed his subject psychologically and sculpturally on paper. His drawings are his journal, where we can read his thoughts, his uncertainties, his evolution, his numerous efforts to remember the subjects that held his interest during his early phase on Tinos, during the German but also the final, Athens period, too. The ‘confused’ drawings of his earlier years later started to gain stability and clarity, revealing a great artist who could be compared to those of global renown such as, for example, Picasso,” she adds.

Voutyra’s explanation points to the approach taken by Onassis Culture and the Teloglion in setting up the show. Titled “Give and Take,” it is based on 10 accounting books from Chalepas Senior’s marble business, which Yannoulis used to put down his thoughts and drawings.

The drawings and sculptures brought together under the foundation’s roof “paint a story about a constant quest for art, a story of decline and resurrection,” notes Onassis Foundation President Anthony S. Papadimitriou.

The three phases of Chalepas’ career are distinctive in the 150 sculptures, drawings, casts and archival material brought together from the Onassis Foundation collection, from museums and from private collections. These are the periods of 1870-78, when he was a student at the Athens and Munich schools of fine art and just after his return to Greece; 1902-30 when he moved back to his native Tinos after years in a psychiatric hospital in Corfu; and 1930-38, when he was back in Athens. Despite the marked differences in the work produced during these periods, however, there are subjects and motifs that span his entire oeuvre, such as Medea, the satyr, Eros, beauty, Oedipus and Antigone.

© teloglion.gr

“Many of his drawings look like smudges, but if you isolate the details in all the different layers, you can distinguish the subjects,” explains Voutyra. A female figure in a yoga-like pose, for example, is visible on one side of the drawing of a sleeping princess in the composition “Fairytale of the Beauty,” which was awarded in Munich in 1874 and takes pride of place in the center of the Teloglion as one of Chalepas’ most imaginative and original pieces.

“Satyr’s Head,” with its sardonic smile – a piece from the same time as the Beauty – is indicative of the new and more incisive theories on Chalepas’ work that have emerged in recent years, and is believed to be associated with the onset of the first symptoms of mental illness.

“I kept doing satyrs. But I almost wrecked this one too. What didn’t I throw at him to make him break? See? Here’s the clay I threw in his face and here the scratches with a pencil and my nails. I wanted to stop his sarcastic laughter, which bothered me. In my madness, I thought he was mocking me. Nevertheless, I love him, he has been good to me, he helped me in my illness,” Chalepas later told fellow artist Stratis Doukas.

There are dozens of drawings pointing to his thought process while creating the 12 pieces in the “Satyr and Eros” series when he was in Germany. His initial references to wrestling, the sense of a threat, to the battle of small against big that are evident in his first sculptures (1918-22) give way later to figures that seem engaged in a tenderer relationship, until his final depiction of the satyr in 1936 shows him in an aged, simpler state, effectively going back to his earliest depictions.

Chalepas worked on the subject of Aphrodite five times, with various results. The clay pieces and drawings seen in the show symbolize female vanity, but also point to his difficulty with female nudes. His two-sided figures from Tinos juxtapose ancient gods on one side and Christian saints on the other, while he was obsessed with the tragic character of Medea, in whom he is thought to have seen his own mother. One of his earliest studies, on Tinos, draws on Eugene Delacroix to aggressively reference the ancient play, but his older work freezes the dramatic moment to focus on the struggle of the decision before the act.

© teloglion.gr

© teloglion.gr

“Genoveva” (based on the folk legend heroine of the Middle Ages) survives in fragments, but there is a photograph taken in 1930 on Tinos showing Chalepas standing beside the complete composition, with the walls of his house in the background. They are covered in pencil and charcoal drawings that were later whitewashed over. A lot of the other clay pieces he made on Tinos have also been lost because of an absence of conservation measures prior to 1922, when the then Ministry of Education (now Culture) sent a craftsman to Tinos to make plaster casts of them. It was based on these casts that the first-ever show on Chalepas was held, at the Academy of Athens in 1925, earning the artist a commendation two years later.

His day-to-day life on Tinos, from 1924 to 1930, occupies a special part of the exhibition as he went back to the mythological and religious motifs that informed his earliest work when he returned to his native island.

Standouts from his Athens phase, meanwhile, include his self-portrait and the drawings he did for busts of several relatives, including his niece, Eftychia, who is also the subject of a double-sided piece, in which he is on the other side.

Chalepas’ bizarre habit of hiding older sculptures inside newer ones is also highlighted at the Teloglion. His “Hecatoncheiry,” for example, was smashed in the big Athens earthquake of 1981, only to reveal another smaller head inside it. His habit of hiding work seems to point to a desire to protect pieces he treasured rather than to a lack of materials or an intention to destroy.

“The study into Chalepas’ work does not end with this exhibition,” explains Voutyra. “Quite the opposite: The 10 books of drawings presented for the first time in their entirely only open new lines of inquiry.”

One of these concerns his father’s workshop, which hosted some of the greatest sculptors of that time. The books also contain details of the business and show that every one of the great Tinian marble producers and sculptors worked with Ioannis Chalepas at one time or another. Those same pages demonstrate the inner workings of Yannoulis Chalepas’ creative process, drawings with such detail and so much information pointing to the sheer caliber of his oeuvre.

“It will take a lot more work to crack the code of how this modern sculptor thought, to dig deeper below the surface of the legend that his tragic fate and novelesque life created,” says Voutyra.

This article was previously published at ekathimerini.com.

Michael Rakowitz’s acclaimed “Lamassu of Nineveh…

This season, the iconic Athens venue…

Fresh polling shows growing UK support…

With over 50 events spanning music,…