The beaches of Epanomi on the outskirts of Thessaloniki are usually a good option for people in the northern port city who want to take a summer swim in clean waters without having to schlep to Halkidiki. Potamos is among the most popular, drawing hundreds of bathers every day in the warmer months.

One of those visitors became intrigued by a small bump on rocks near the beach. From 1999 to 2001 Nikos Bacharidis slowly dug around the bump until he brought to light a part of a fossil of a prehistoric tortoise. The amateur paleontologist was excited by his discovery but did not become aware of its significance until 15 years later, when the professional sculptor’s name was given to his discovery: Titanochelon bacharidisi.

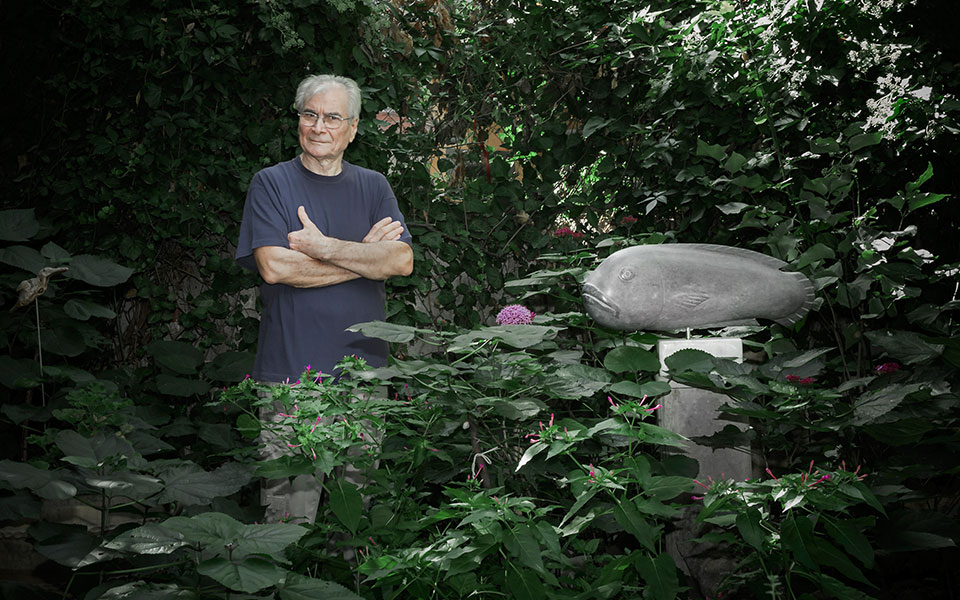

Bacharidis’s studio is easy to miss, tucked away in a basement on a narrow street in the Toumba neighborhood. To most visitors, his sculptures look like weird shells, but more discerning customers ask him about the rocks in his display cases and learn about his adventures as an avid amateur paleontologist and collector of fossils.

“The eyes can be taught to see what was invisible beforehand,” he says, as I move carefully, fearful that I might knock to the floor and smash one of the fossilized life forms dating from millions of years ago. “I started exploring fossils thanks to sculpting,” he adds in his soft voice.

Energetic despite his 75 years, Bacharidis’s eyes light up with childlike enthusiasm when he speaks of his fossil collection. He explains that when he started sculpting, he liked to look for and experiment with natural ingredients. He didn’t have the opportunity to receive formal training, but as he did later too with paleontology, he studied his passion in great depth.

“In sculpture you have to transfer the form you have in your mind to the marble. Likewise, with the discovery of fossils, you need to apply the techniques of sculpture to remove the shell and discover what’s inside. It was an adventure that I enjoyed immensely,” says Bacharidis.

When he was 35, he went hiking in the area of Grevena, west of his native Thessaloniki, a part of the country he now knows to be rich in fossils.

“I sat down to rest and by chance saw an odd fossil. It looked like the horn of some animal and that’s exactly what I thought it was. I then started to suspect that it was something else because I had seen a lot of them here and there. They were rudists,” he remembers, referring to a category of reef-building microorganisms which flourished during the Cretaceous period, some 145 million years ago.

As he became more familiar with the shapes of fossils, otherwise uninteresting parts of the countryside became his playground. “Where once I saw nothing, I started seeing fossils. My eyes became more familiar with their forms, more observant and could discern different forms and shapes.”

He speaks with excitement about the ammonoids, a type of marine mollusc that lived in the area of Epidaurus in the northern Peloponnese at the same time as the dinosaurs, the fossils he found at Pikermi, north of Athens, and the different strata of soil protecting layers of fossils near Thessaloniki.

“I try to reconstruct scenes in my mind, to see what was happening at the time, to envisage landscapes I have never seen but have read so much about,” says Bacharidis. “It’s an escape from the daily routine into a world that is absolutely gripping.”

Around 5 million years ago Halkidiki was attached to the Katerini plain and the area of the Thermaic Gulf was all rivers and lakes. The climate was much warmer and the conditions in the area were ideal for giant tortoises that could reach over a meter in length, much like the one Bacharidis displays on a pedestal in his studio.

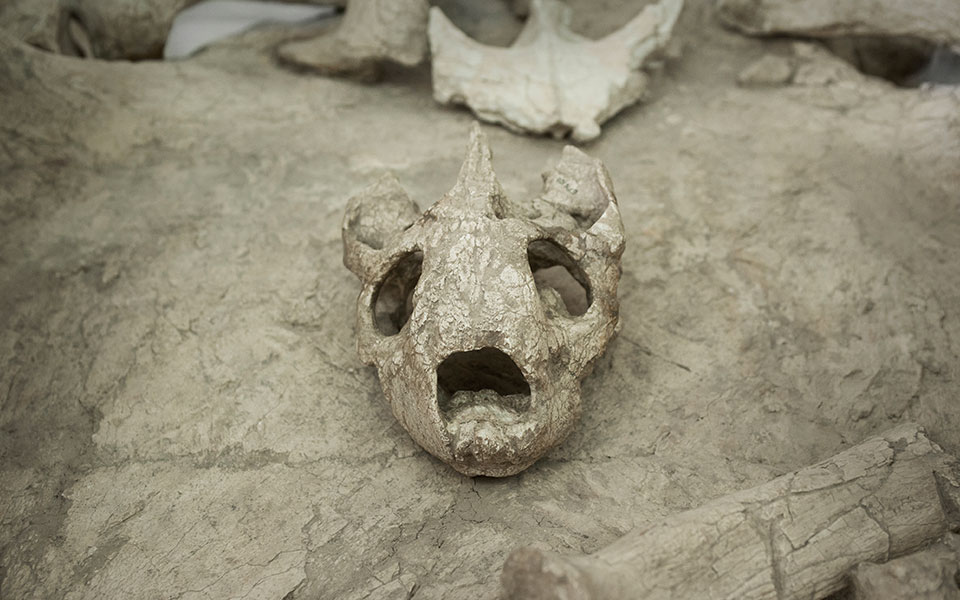

The skeleton and skull of the tortoise he discovered on the beach at Epanomi is one of the most complete fossil samples of the animal ever to have been discovered in Europe, according to experts at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki.

Using an old oar and a few rudimentary tools, Bacharidis spent two years perched on the edge of a cliff, painstakingly chipping away at the rock and sweating in fear that he’d accidentally damage his discovery. After collecting all the pieces he retrieved and cleaning them up in his studio, he started the task of assembly.

“I had never done anything like it before. I had no guide to follow, but again sculpture came to the rescue,” he says, explaining how he allowed the shapes of each piece to show him how to fit them together. “Thankfully each one found its place.”

This article first appeared on ekathimerini.com