Findings from the fourth season of fieldwork in northwest Crete exploring the sunken city of ancient Olounda (Olous) were recently released by the Ministry of Culture.

A joint team of archaeologists from the Greek Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities and geophysicists from the Institute of Mediterranean Studies (FORTH), accompanied by volunteer divers and other specialists, have been exploring the underwater ruins in northwest Crete, which have a history that stretches back to the Minoan civilization.

The recent fieldwork, conducted last year, forms part of a five-year program of research aimed at investigating remains of the ancient coastal city and its environs near modern-day Elounda, a popular tourist destination in northwest Crete. Started in 2017, the project receives local support from the Municipality of Aghios Nikolaos.

The team have thus far conducted underwater surveys along the coasts of Elounda Bay and the Kolokytha Peninsula, and uncovered the remains of submerged structures on both sides of the Isthmus of Poros, the location of the ancient urban center.

Much of the area is easily accessible from the nearby shoreline, making it a popular draw for snorkelers and swimmers. Visible remains in the shallow waters include wall bases and the outlines of ancient buildings.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

Submerged remains

In earlier seasons, the team recorded evidence of shipping and maritime activity from a range of periods, including sections of an ancient jetty (a loading platform), material used as ship ballast, anchors, and the partial remains of Byzantine and 20th century shipwrecks.

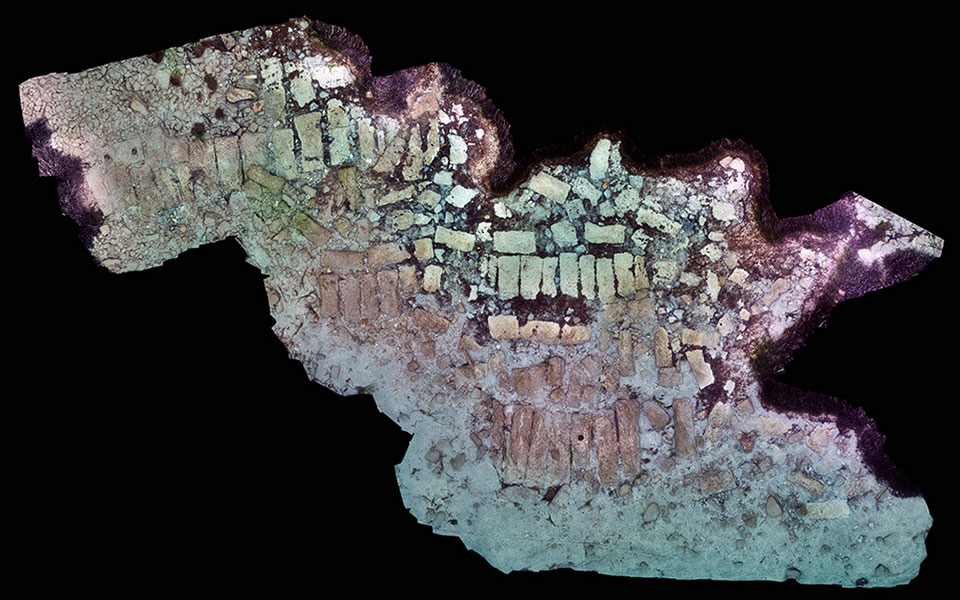

This latest season focussed on the shallow-water area north and south of Poros, clearing away sand and vegetation, and documenting the remains of ancient structures.

The team revealed the upper surface of a large, elongated structure, initially interpreted as part of the city walls or further remnants of the ancient jetty. Only further test excavations around the structure will determine its precise shape and function.

Members of the the Satellite Remote Sensing & Archaeoenvironment Laboratory (GeoSat ReSeArch Lab) conducted a geophysical survey of the seabed using electrical and magnetic resonance imaging, gathering data on the presence of ancient structures buried in subsoil up to depths of 1.5 m.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

Beyond Poros, underwater research continued in the Bay of Krios, east of the Kolokytha Peninsula, where large concentrations of pottery were found on the seabed. Further surveys along the coastline, opposite the islet of Spinalonga, the site of the infamous leper colony, to the Bay of Vathi, revealed more pottery and the remnants of a submerged building.

On the nearby beach, a fresh water source was found, as well as Minoan pottery mixed with a number of purple oysters, used to make ancient dye. In the nearby area of Tsifliki, the sunken remains of buildings and an “elongated structure”, known to the locals as a “road”, were located and photographed from the air using a drone. The structure may have served as the main thoroughfare to the now-submerged building complex on the coast.

During the season, the team took time to host children from the 4th grade of Elounda Primary School, discussing with them various aspects of the fieldwork.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

Ancient Olounda

Ancient Olounda was one of the most important cities of Archaic and Classical Crete, described in the historical accounts of Pseudo-Scylax and Ptolemy. The early inhabitants practiced an early form of democratic government, and worshipped the gods Zeus, Apollo, and Talos, a giant bronze automaton who was said to circle Crete three times daily to protect Europa, the mother of King Minos, from pirates and invaders.

The goddess of mountains and hunting, Britomartis was also worshipped in the city – a “Cretan Artemis” – and honored by the Britomarpeia festival.

Remains of an earlier settlement in the area of the Poros Isthmus have been dated as far back as the Minoan Bronze Age. Throughout antiquity, the isthmus itself was wider and at a higher level.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports

© Metropolitan Museum of Art - https://www.metmuseum.org/toah/works-of-art/42.57.1

According to ancient writers, the inhabitants of the city were engaged in maritime trade and the production of dye, which involved the crushing of marine shells. They were also involved in the mining of whetting stones, used to sharpen metal tools.

The city disappeared beneath the waves either because of a landslide or as a result of the large earthquake of 780 AD. Artifacts and inscriptions from the site are on display in the archaeological museum of Aghios Nikolaos and at The Louvre in Paris.