“Let’s go, Irakli!” Dimitris Efraimoglou, managing director of the Foundation of the Hellenic World, exclaimed happily to the technician in charge of the projectors of the Tholos. This is the dome-shaped virtual reality theater of Hellenic Cosmos, the foundation”s cultural center.

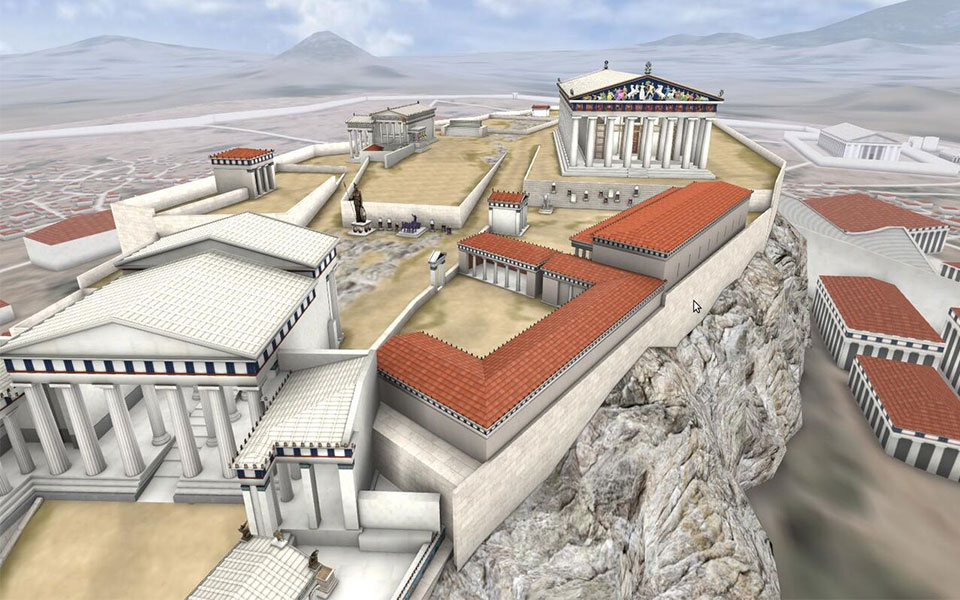

Seated in one of the theater’s velvet seats, I feel like a crew member of a space ship landing in Pericles’s Athens in the 5th century BC. As if by magic, the buildings of the Sacred Rock of the Acropolis loom in front of us, impressive and with many colorful details.

Imposing doors open seemingly in front of our noses, revealing rooms with statues, artifacts, and weapons while around us are temples and other buildings, such as the home of the Arrephoroi, the young women who were chosen to serve the goddess Athena for a year. The room with their beds opens up before us, together with the space where they would play ball games, when not required to help weave the robes that would be used to dress the wooden statue of the goddess at the Erectheion during the Great Panathenaia festival.

A New Production

For the duration of the thrilling experience of being immersed in this virtual world, the voices of the museum guides Niki Tsiouni and Panagiota Stellaki appear to belong to members of the time machine’s crew, giving us a tour of structures lost to time: the sanctuaries of Zeus Polieus (Zeus the city-protector) and Artemis Brauronia, the Chalkotheke (‘bronze storehouse’), the elaborate decoration of the Parthenon and its magnificent gold and ivory statue of Athena.

This tour of all of the great works of Athenian architecture, created when Athens was at the peak of its political, military and artistic powers, is the latest interactive production created by the Foundation of the Hellenic World. It was produced in cooperation with the professor of classical archaeology Panos Valavanis, a beloved figure at the University of Athens who speaks in a manner that is direct and easy to follow. He has frequently noted how, “In the Parthenon, as in all of the major works, nothing is by chance.”

The elegant structure to our right is the temple of Athena Nike. The Propylae, at the entrance to the Sacred Rock, “the most monumental of ancient Greek architecture,” seems to embrace thousands of visitors. The Pinacotheca (picture gallery) with its paintings and chaise longues resembles a clubhouse for officials.

And there is the bronze statue of Athena Promachos; colossal, standing at 9 meters tall, it is a work by the great sculptor Pheidias that was erected in 460 BC on the Acropolis. The tip of her spear and the crest of her helmet can be seen from the sea. At the long building close to the south wall we see what the Chalkotheke once looked like, which stored offerings and weapons – the goddess’ fortune.

The Erectheion was the most important temple of the Acropolis, as it was here that the ancient wooden statue of Athena was kept, which was dressed every four years in a new robe during the Great Panathenaia festival. “A singular and complex construction which, while a temple, did not have symmetry and regularity.”

But one’s gaze is drawn to the level roof which, instead of columns, is supported by six female bodies, each 2.20 meters in height. The Caryatids, with the subtle movement of one of their legs, as if walking in procession, are the works of various sculptors who copied a prototype. Their bright colors are startling.

The Parthenon

From there we hurtle to the pinnacle of ancient Greek architecture: the Parthenon. It is built from 16,500 marble elements and 9,000 marble shingles. Its symmetry, its “balanced relationship in three dimensions” and its subtle refinements and optical illusions that make it more pleasing to the eye make the monument unique. And here its sculptural decorations are rendered in exquisite detail.

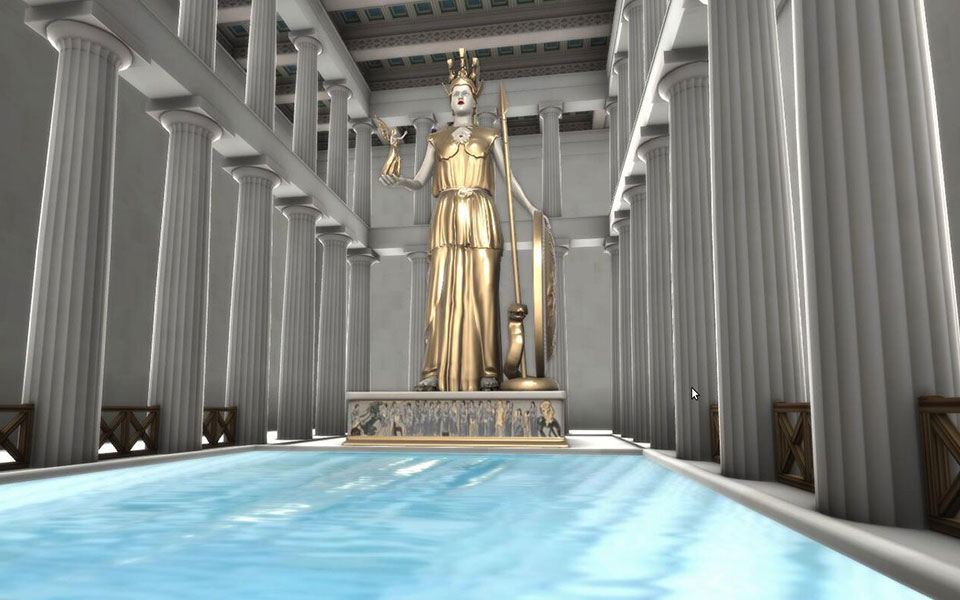

In the triglyphs, the metopes and the pediments, blue vies with red and green. Of the figures, the men’s bodies are painted brown, whereas those of the women are white. But the grandest figure is concealed in the Parthenon’s interior: the 12.75m gold and ivory statue of Athena Parthenos. The bare parts of her body are made of ivory, her robes of gold. Even her sandals are decorated, with the soles featuring a carved rendering of the battle against the centaurs around their edges. A pool of water in front of the statue ensured the appropriate humidity for the ivory, but it also creates a mystical atmosphere, with a light breeze creating ripples on its surface.

The Odeon of Herodes Atticus

The journey ends in post-classical Athens, where we are impressed by the semi-circular roof of the Odeon of Herodes Atticus which did not rest on internal supports so as not to obstruct the view of any of the 6,000 audience members. This theater, with its impressive multi-storied facade, full of niches for statues, was a gift from the wealthy Athenian philosopher Herodes of Attica, in memory of his beloved wife Rigillis.

Our tour complete, the lights fade on and Dimitris Efraimoglou, together with his wife Sophia Kounenaki-Efraimoglou (executive vice president of the Foundation of the Hellenic World and head of the Hellenic Cosmos cultural center) speak with satisfaction about the latest production.

It was exactly 20 years ago that Hellenic Cosmos brought a new world to Athens, making use of cutting-edge technology in all of its activities. In 2005 it created the Tholos theater. Architecturally striking, it features a 2,260 sq.m. hemispherical projection surface at an angle of 23 degrees. 500 people visit the theater daily, and even more over the weekends when number 254 on Pireos Street resembles a busy beehive.

“When we created Kivotos [a cube-shaped virtual reality room] the head of thematic museums of Silicon Graphics told us, ‘you will be victims of your own success’. He was right. On weekends people would come from outside of Athens and complain because they couldn’t get a place. Tholos was essentially something that our audience demanded,” Dimitris Efraimoglou says.

It was his personal wager. The idea was born in 1994 at the largest computer fair in the US. “It was a little before the Yugoslav war and they showed us a program used by the US military to avoid snipers when entering deserted towns. I thought then that we could use this technology for a good purpose, for our culture. That’s how Tholos was born.”

The way professor Wolfram Hoepfner talked after seeing the production about ancient Miletus, “was like receiving a Nobel prize from him,” he says. “The man who had excavated sites all across Asia Minor, including Miletus, told me: ‘I have a better sense of what ancient cities were like have seen the reconstruction.”

The thoughts of three schoolgirls in the guestbook: “When they told us that we were going to a museum we all said, ‘no!’ But we will come back!” are also a vindication.

Meanwhile Sophia Kounenaki-Efraimoglou has an eye on the future. “The collaboration between the FHW and the municipality of Igoumenitsa is the beginning of a turn to the periphery. When the audience can’t come to Athens, the FHW goes to their town. Our next goal is Crete and Santorini. As for our next production, it will be dedicated to Knossos.”