The 2017 fact-based drama “The Post” revolves around the Washington Post’s decision in 1971 to publish the Pentagon Papers. A similar thriller unfolded at the offices of the Sunday Times of London a few years earlier, in 1968. The contentious issue may not have brought about the downfall of the British government, but it did deliver a major blow to a regime hundreds of miles away in Greece, smashing the image the colonels’ dictatorship (1967-1974) was trying to cultivate abroad. One of the protagonists of this journalistic drama was the historian Richard Clogg.

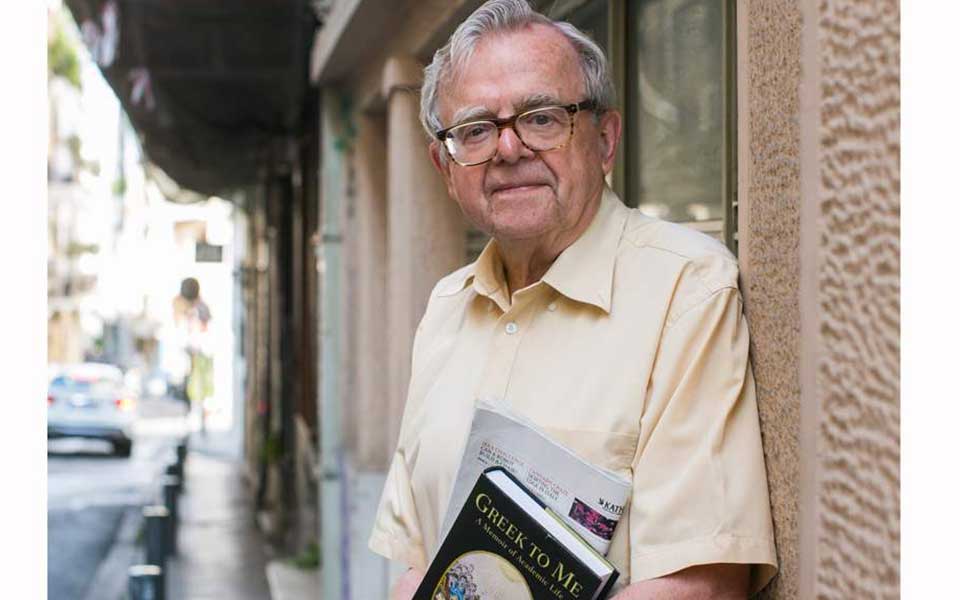

Best known here for his book “A Concise History of Greece,” Clogg’s contribution to the anti-dictatorship movement, which he supported from both Athens and London, is not so well known in Greece. However, he was friends with Kathimerini’s previous owner, Eleni Vlachou, and other prominent anti-dictatorship figures like Alexis Dimaras during a period that he describes in great detail in his book “Greek to Me: A Memoir of Academic Life,” and was an active proponent of the movement.

Sitting on the balcony of his hotel against the backdrop of the Acropolis, the 79-year-old historian spoke to Kathimerini recently about those days and the book, which is currently being translated into Greek.

A Hellenist who became fascinated by Greece on his first visit as a university student, Clogg crossed swords with the junta’s propaganda machine on several occasions as a critic in the Times Literary Supplement, where he made a point of criticizing books that cast the regime in a positive light. He also helped Vlachou, who had shut down Kathimerini in protest at the junta and moved to London, where she published the English-language anti-dictatorship magazine “Hellenic Review.” Then one day in September 1968, Vlachou gave him a document that she wanted translated into English.

“I was sitting at the British Library when I read it and immediately realized that it was dynamite,” says Clogg. “I called Eleni saying that this was quite important to appear in your magazine – I didn’t put it in those terms – but asked her if I could give it to the Sunday Times and she agreed.”

The report had been sent by Constantine Karamanlis, who had received it from a source at the junta’s headquarters. It revealed that the junta’s public relations officer was paying MP Gordon Bagier to promote a positive image of the regime.

Clogg asked academic and historian Alexis Dimaras, who was living in Athens at the time, to help with the translation. “It was so good that they were looking for the mole in London when he was in Athens,” he says laughing.

When Maurice Fraser, who was in charge of public relations for the junta abroad, learned of what was going on, he obtained an injunction banning the publication of the report a few hours before it went to press. The ban subsequently raised the issue of freedom of the press and articles were written about it in the media in Britain and elsewhere.

“The granting of an injunction necessarily added an aura of mystery to the proceedings and quickly transformed what might otherwise have been a scandal with a short shelf-life into a political cause celebre of major dimensions,” Clogg writes in his book.

“A statement issued by the Sunday Times maintained that, following the injunction, ‘newspapers, television and radio in this country and abroad had shown the keenest interest in the story.’ Even Pravda had a piece on the emerging scandal entitled ‘Greek machinations.’”

“I think this was my greatest contribution to the anti-colonel campaign,” says Clogg.

Why did he choose to write this book now? “I wanted to leave some record of my activities. I wish many people did that. Children usually don’t ask parents about aspects of their lives. It’s only after they are gone,” says the 79-year-old historian.