Stories Told by the Stones of Crete

A forgotten world comes to life...

© AP

Philip II would be proud. The brash, battle-scarred king of ancient Macedonia (ruled 359-336 BC) was a man of action, unsatisfied like his predecessors simply to rule over the traditional Macedonian territory, extended long before by Alexander I (498-454 BC) but since then collapsing, whose royal heartland lay near Veria, south of present-day Thessaloniki.

During his reign, Philip set out determinedly to expand his kingdom far beyond any previously known frontiers. He successfully took over or consolidated surrounding regions through a combination of hard-fought military campaigning and shrewd diplomatic moves that often involved new ties and loyalties created through seven calculated marriages. His fourth, best-known wife, who bore him his destined-to-be-great son Alexander, was Olympia – a princess-turned-long-suffering queen and fiercely protective mother who hailed from Epirus, to the west.

Tomb II's golden larnax

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Getty Images/Ideal Image

Simple and lavish jewelry from Aigai, revealing the predilection of noble Macedonian noblewomen for personal elegance.

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Getty Images/Ideal Image

Not only did Philip establish a remarkable sphere of hegemony that stretched from Paeonia (now North Macedonia) to southern Greece and Thrace (some 43,000 square kilometers), but he laid the groundwork and introduced innovative military weapons and tactics that would allow Alexander to elevate Macedonia even further, as master of a “global” empire reaching far to the East.

Today, present-day Macedonians, led by archaeologist and ephorate director Angeliki Kottaridi, are once again putting northern Greece on the map and in the spotlight, as a new program to develop and promote the ancient Macedonian capital of Aigai (Vergina) comes to impressive fruition. Particularly exciting is the foundation of a large new museum at Aigai, which is slated to open around Eastertime next year (2022), according to Kottaridi, and looks about to become Greece’s latest world-class museum – showcasing the extraordinary achievements, lives, art, architecture and artifacts of Philip, Alexander and other royals and nobles who once inhabited or were laid to rest at Aigai.

The Rape of Persephone Hades carries Persephone off to the Underworld. Fresco from Tomb I. Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aigai.

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, AMNA

Traveling today into Macedonia and the area of Thessaloniki, visitors are often struck by a particularly distinctive feature of the age-old landscape: low, prominent mounds, known as tumuli, which can be seen in many places rising protectively over the ancient burial spots of well-to-do Macedonian elites or respected warriors. The Pieria region near the Aliakmon River is one such district dotted with tumuli – more than 500 in the core Vergina/Palatitsia area – where, in the 1970s, the famous archaeologist Manolis Andronikos and his colleagues were systematically exploring these features in search of definitive evidence of the ancient Macedonian capital. An apparent palace structure had already been brought to light at Vergina (1961-1970) but in 1976 Andronikos began excavating the nearby Great Tumulus.

The following year, as the painstaking excavation slogged on, penetrating deeper and deeper into the mound, the team finally made a remarkable discovery: an unspoiled, barrel-vaulted chamber tomb adorned with an elegant, Doric-style, temple-like façade. Behind its great stone doors, Andronikos found two unlooted rooms filled with luxurious gold, silver, ivory, bronze and iron objects of personal, ceremonial or utilitarian purpose; traces of richly decorated textiles; burned sacrificial foodstuffs; and, most importantly, a small golden chest (larnax) containing cremated human remains that the excavator identified as Philip II. A second burial in the tomb’s antechamber has been attributed to Meda, the king’s sixth, Thracian wife.

Intricately carved ivory figures, once adorning the chryselephantine dining couch of Alexander IV (Aigai, Tomb III).

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, VISUALHELLAS.GR

Since these extraordinary discoveries on November 8, 1977, much scholarly research and public interest have focused on a complex array of architectural, artifactual, art-historical and osteological evidence. Complicating the issue has been the fact that no personal names were originally attached to particular tombs by the ancient Macedonians, as we do today with inscribed, identifying gravestones; and that many Macedonian royals or other affluent citizens were regularly interred in costly, architecturally elaborate tombs filled with lavish personal items and other impressive grave goods.

The difference with Tomb II at Aigai is that the burial was never plundered, but rather left in a pristine condition. The contents demonstrate just how prosperous the elite class of fourth-century BC Macedonian society had become. With over a thousand graves now having been excavated, many of them still containing traces indicative of high social status, one begins to understand the extraordinary riches once to be found in Aigai’s necropoleis – and the enormous attraction for ancient tomb raiders, who would often loot affluent graves, especially those of prominent figures, even only a short time after they had been sealed up. Aigai, with its hundreds of burial mounds, must have posed a tantalizing target, as made apparent in 273 BC when Pyrrhus of Epirus invaded the city. Diodorus Siculus (22.12) records that after he sacked Aigai, Pyrrhus left his Gauls there; they, understanding the “ancient custom [that] much wealth was buried with the dead at royal funerals, dug up and broke into all the graves, divided up the treasure, and scattered the bones of the dead.”

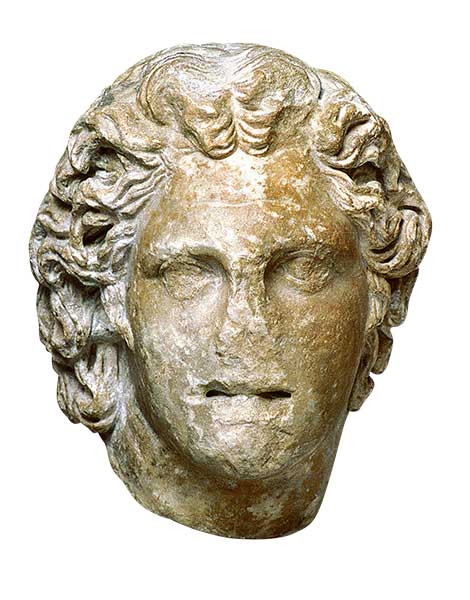

Portrait of Alexander the Great.

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Getty Images/Ideal Image

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Getty Images/Ideal Image

Now, the latest scientific findings from renewed analyses of both the pristine Tomb II and the adjacent severely looted Tomb I leave us with an even more perplexing archaeological puzzle. Despite media reports to the contrary, the problem of identification of the deceased in the much-debated Tomb II remains unsolved. On the one hand, physical anthropological studies of the human remains in the antechamber of Tomb II, by Theodore Antikas (2014), in combination with associated artifacts including a Scythian-style arrow quiver (gorytus) and a pair of leg-protecting greaves of unequal length, have shown that the female occupant was very likely Meda of Odessa, a Thracian princess, horsewoman and archer, aged 30-34 years old, whose left leg appears to have been shorter than her right, due to a terrible, healed fracture detected in her left tibia. This fascinating identification would suggest her husband, Philip, was likely buried in the tomb’s main chamber.

On the other hand, a meticulously documented analysis of human remains from Tomb I, by physical anthropologist Antonis Bartsiokas (2015), has revealed the presence of three individuals, including a male (about 45 years old), a female (18) and a 2-3-week-old infant. Their ages precisely correlate with the ages of Philip, his last wife, Cleopatra, and their young child, born just weeks before the king was assassinated in 336 BC in Aigai’s theater, just beside the royal palace. Even more intriguing, the male was found to have suffered a “flexional ankylosis” of the left knee, which resulted in “the fusion of the tibia with the femur … [a condition] caused by a severe wound to the knee, likely affected by a penetrating instrument, such as a fast-moving projectile (e.g. a spear).” The discovery of a distinctive, healed hole in the male’s knee points directly at Philip, who was well known to have suffered exactly such a spear wound three years before his death and to have exhibited a bad limp. So, was Philip in Tomb I, or Tomb II? No more recent studies, or the results of reported DNA analyses, have yet been published. Thus, the great mystery continues…

Remains of the newly re-investigated and reconstructed royal palace at Aigai.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Regardless of which Macedonian royal lies in which tomb, the identity of Aigai as the capital of Philip’s kingdom/empire is clear. The historian Herodotus (5th century BC) informs us that Perdiccas I, the founder of Macedonia, left Argos (about 700 BC) and eventually settled “near the Gardens of Midas,” in the “shadow of the mountain called Vermio,” not far from the confluence of the Aliakmon and Lydias (now Loudias) rivers and present-day Veria (13 km NW).

Aigai means “goats” in ancient Greek, and it was here amid rolling, pastoral plains that many generations of leading Macedonians flourished. Archaeological evidence indicates the site of Aigai was already well populated by the 10th century BC, becoming the Argead dynasty’s primary city (asty) in the mid-7th century BC. Recent investigations by Kottaridi show the palace was constructed during the reign of Philip. As Pella similarly developed during the 4th century BC and became the new royal seat and the birthplace of Alexander, Aigai came to serve as a seasonal center, its palace as a political, ceremonial and library-equipped philosophical gathering point.

Between Pella and Aigai also lay Mieza, with its Sanctuary of the Nymphs and nearby gymnasium, where Alexander was tutored by the philosopher Aristotle. This was the verdant Macedonian homeland, the nurturing cradle from which Alexander emerged to take up the imperial reins after his father’s assassination and to boldly begin annexing a far-greater empire. Under Cassander’s later rule, following Alexander’s own demise (323 BC), Thessaloniki was founded (315 BC), a new Antipatrid dynasty was launched and Aigai appears to have become more of an historical monument to Macedonia’s regal past, whose defenses were reinforced with newly constructed city walls. With Rome’s subjugation of northern Greece (168 BC), however, Macedonia’s capitals were despoiled and began to decline, with much of Aigai finally disappearing beneath a major landslide in the 1st century AD.

Gold foil relief of warriors.

© HELLENIC MINISTRY OF CULTURE & SPORTS/Ephorate of Antiquities of Imathia, Archaeological Museum of Thessaloniki, Getty Images/Ideal Image

Since the late 1990s, Vergina has been home to the unique Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aigai, where one can enter the reconstructed Great Tumulus and view “underground” its impressive graves. Now, however, new light is being shed on Philip, Alexander, Aigai and all of ancient Macedonia, as Vergina is set to become host, under Kottaridi’s leadership, to a vast archaeological park encompassing not only the Great Tumulus, but the entire site of Aigai that underlies and extends beyond the village. In addition to its main building and displays, now nearing completion at the entrance to Vergina, this new Polycentric Museum of Aigai, financed in part by regional authorities and the EU, will include the recently re-excavated and freshly presented palace, the theater, the existing Museum of the Royal Tombs and the nearby cluster of earliest Temenid-dynasty tombs (Cluster C).

Entrance ramp of the Great Tumulus and "underground" Museum of the Royal Tombs of Aigai, Vergina.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

Through four main exhibitions within the enormous new museum, the focus now will be on Aigai’s overall urban landscape, with all of its royal, sacred, public, domestic, defensive and funerary features.

The first exhibition, relates Kottaridi, will be a temporary, regularly changing, thematic exhibition. The second, in a large, glass-roofed atrium, comprises a 30m-long x 7m-tall reconstruction (with mostly original material) of the palace’s upper floor (the lower is currently being reconstructed in situ), revealing all the elements of the palace’s intricate architecture. The third, in another atrium, presents statuary; reliefs; important, mostly 4th-century BC inscriptions; royal dedications; and votive offerings.

The fourth, and most extensive, illuminates life in ancient Aigai. Here visitors will find evocative traces of the city’s human population, including graffiti, impressions of fingers and feet preserved in clay, representative faces depicted on figurines and even nails and door locks from ordinary homes. Displays also reveal Macedonian weaponry, including Philip’s innovative sarissa (long spear); the century-by-century evolution of banqueting – a core cultural practice – with all its accoutrements; the world of women; and the funerary practices and evidence of early burials dated to the pre-Philip era.

The new Polycentric Museum will also be home to the virtual museum entitled Alexander the Great: From Aigai to the World, which will employ advanced information technology and technological tools to present, “in an integrated, scientifically valid and … appealing way,” the life and achievements of Macedonia’s great empire-builder and progenitor of the Hellenistic world. The building, scheduled to open in April 2022, will also incorporate fully-equipped conservation laboratories, storage spaces and facilities for visitor reception and educational programs. The first temporary exhibition, in collaboration with the Athens Numismatic Museum, will highlight the influence at Aigai of the newly expanded Greek World (oikoumene), as manifested through coins, sculptures, inscriptions and other objects that illustrate the inflow of foreign material culture and even the individual faces of foreign leaders (as portrayed on coins) now under the dominion of the far-reaching Macedonians.

Online:

A forgotten world comes to life...

Without noise or concrete, the Old...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

Aigai’s newly restored Macedonian palace represents...