Nestled on the far eastern side of the Aegean Sea, the island of Chios boasts a rich tapestry of history and culture that stretches back millennia. Throughout the Middle Ages, in particular, the island enjoyed a lengthy period of prosperity and influence as a key regional center of the Byzantine empire. Recognizing its strategic importance, successive Byzantine emperors fortified the island in response to the expansion of Turks to the Aegean coast of Asia Minor, and established direct trade maritime routes that connected it to the empire’s capital, Constantinople.

Amidst this backdrop, the spectacular Nea Moni, or “New Monastery,” was founded with imperial patronage in the mid-11th century, by emperor Constantine IX Monomachos (r. 1042-1055) and his wife, empress Zoë Porphyrogenita. Situated in the island’s mountainous interior, between the picturesque villages of Avgonyma and Karyes, it is said that the monastery was built on the location where three monks, Nikitas, Ioannes and Iosif, found an icon of the Virgin Mary, hanging from a branch of myrtle.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

Dedicated to Theotokos, “Mother of God,” the monastery soon emerged as a beacon of religious and architectural excellence, and its interior mosaics among the finest examples of “Macedonian Renaissance” art in Greece. Covering an area of approximately 17,000-square-meters, the monastery complex was surrounded by high defensive walls, and featured a fortified tower at the western edge of the enclosure, reflecting the era’s tumultuous political climate. In its heyday at the turn of the 14th century, with a community of some 800 monks, the monastery’s estates extended across one third of the island, and was one of the wealthiest in the Aegean.

Today, Nea Moni stands as a testament to Greece’s rich Byzantine heritage, attracting visitors from around the world. Inscribed on UNESCO’s list of World Heritage Sites in 1990, along with the 11th-12th century monasteries of Daphni in Attica and Osios Loukas in Viotia, Nea Moni remains one of the most outstanding examples of Middle Byzantine religious architecture in the country.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

© Michel Bakni - Public domain

Restoration Project

In a recent statement, Greece’s Ministry of Culture announced plans for an ambitious restoration project of the nearly 1,000-year-old monastery, spearheaded by the Ephorate of Antiquities of Chios. The project will focus on revitalizing the monument’s defensive tower and fortification enclosure, opening up the previously inaccessible western section of the monastery for visitors to explore.

With a budget of 700,000 euros from the EU’s Recovery and Resilience Fund, the restoration effort is part of a broader initiative by the Ministry of Culture to preserve and showcase the rich cultural heritage of the northern Aegean islands.

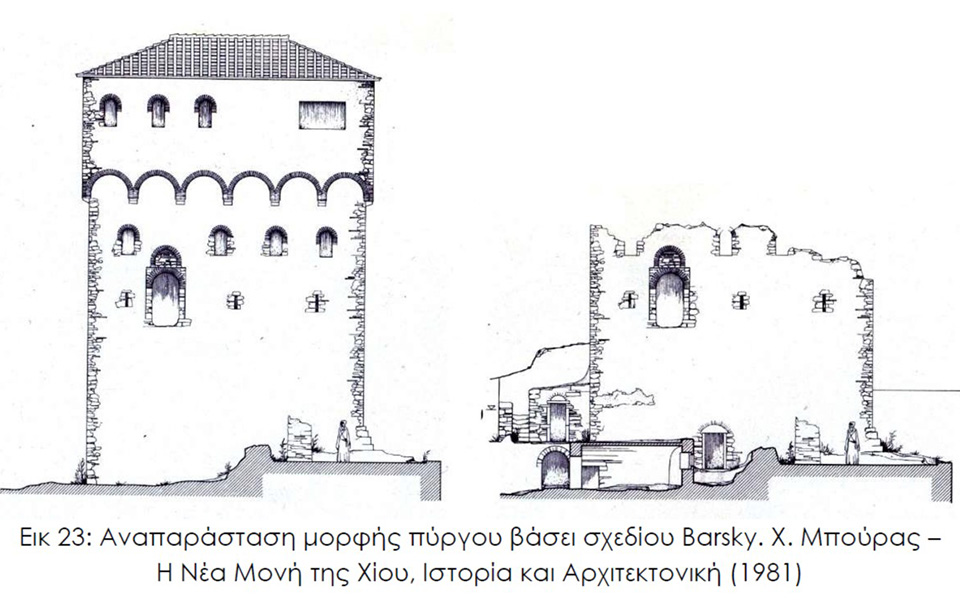

Restoration efforts will focus on reconstructing and reinforcing the collapsed sections of the defensive walls and tower, damaged following the destruction of Chios in 1822, in the early stages of the Greek War of Independence, and, later, the catastrophic earthquake of 1881. According to sources, the tower, which dates to the first construction phase of the monastery, housed the library and the treasury during the 17th and 18th centuries. Originally, it had a ground floor and an upper floor (now lost), with a wooden mezzanine.

Of the original structures from the 11th century, the Katholikon, the monastery’s central structure, built on a characteristic cross-in-square plan with a large dome, two smaller churches (dedicated to the Holy Cross and to Agios Panteleimon), the dining hall (“trapeza”), the reception hall or “triklinon,” and underground water cistern (“kinsterna”) are well preserved today. Outside the walls, near the monks’ cemetery, there is a small chapel dedicated to Agios Loukas.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture

In the press statement, Greek Culture Minister Lina Mendoni emphasized the significance of these interventions and how they will contribute to the island’s cultural and economic vitality: “Through the ongoing interventions, the prominent Byzantine monument and historical landmark of Chios becomes accessible and visitable in its entirety,” adding, “these projects are included in the ‘Cultural Map of Development and Prosperity,’ which aim to strengthen the social and developmental dynamics of our islands.”

Restoration works on the monks’ cells (“kelia”), dating from later periods, are also included in the project, enhancing the overall visitor experience and offering insights into the living conditions of the monks throughout the monastery’s history. It is hoped that the ground floor of the complex will host informative exhibitions about the tower and the monastic fortifications.

Regarding the duration of the project, Mendoni remarked: “Our goal is for the project to be completed by 2025, to be delivered to the island’s residents, contributing to the improvement of their quality of life, enhancing the competitiveness of the tourism product, and investing in the sustainable development of the island ecosystem.”

© Public domain

A Symbol of Resilience

Over the centuries, Chios witnessed a series of historical upheavals, including invasions by foreign powers and internal strife. In 1346, the island fell under Genoese (Latin) rule, marking a period of cultural exchange and economic growth. The Republic of Genoa, renowned for its powerful navy, brought new trade opportunities to Chios, transforming it into a bustling commercial hub in the wider eastern Mediterranean.

However, the island’s fortunes took a downturn with the arrival of the Ottoman Turks in the mid-16th century. Despite valiant resistance, Chios eventually succumbed to Ottoman rule in 1566, ushering in a new chapter in its history. Under Ottoman dominion, Chios experienced a decline in its once-thriving economy, as trade routes shifted and the island’s strategic significance waned.

Throughout these turbulent times, Nea Moni stood as a symbol of resilience and spiritual fortitude. During the Greek War of Independence, following the destruction of Chios in April 1822, 2,000 people sought refuge in the monastery. Ottoman troops stormed the enclosure and set fire to the Katholikon, slaughtering many inside. Decades later, in 1881, the monastery sustained further damage, including the collapse of the, now restored, main dome, and a bell tower from the early 16th century.

Despite these challenges, the monastery remains a bastion of Byzantine Greek culture, preserving its architectural splendor and religious heritage for future generations. Converted into a convent in 1952, it once again became a male monastery in 2014, and is home to a small community of monks.