Greece’s Ancient Ruins as Accidental Arks of Biodiversity

New research reveals that Greece’s most...

Dimitris Pantermalis described Barack Obama as being well read about the ancient world and fascinated by the museum’s statues. The then US President also expressed a desire to return to the museum with his family.

© © AP Photo/Pablo Martinez Monsivais

The late Professor of Archaeology and Director of the Acropolis Museum, Dimitris Pandermalis, who died today, September 14, 2022, was first and foremost a field man, a pioneering archaeologist who dedicated nearly 50 years of his life to excavating the ancient Macedonian city of Dion and its sanctuary of Zeus.

Turning to museums, he was appointed Director of the Acropolis Museum in Athens, a position he held from its opening in 2009 to his death. During his time as Director, he pioneered the way in which exhibits and collections were organized and displayed, quickly earning the museum high praise among the international scientific community, academics, museologists, and millions of visiting public from around the world.

In this interview, which featured in the summer 2017 edition of Grande Bretagne Magazine, journalist Natassia Blatsiou asked questions about the significance and enduring popularity of the Acropolis Museum, the role of archaeology and museums in the 21st century, his guided tour of the museum with former US President Barack Obama, and what can be done regarding the issue of the Parthenon Sculptures:

Bathed in warm Attic sunlight, the Parthenon Gallery occupies the third floor of the Acropolis Museum.

© Shutterstock

Τhrough the floor-to-ceiling windows of the restaurant of the Acropolis Museum, I stare out at the Parthenon awash in the warm Attic sunlight. In front of me, dozens of small stories are unfolding as tourists make their way up the slopes of the Sacred Rock: small, insignificant occurrences that can keep one occupied for hours. My gaze is drawn to a large pine tree under which a group is taking a rest. It is a tableau seemingly straight out of some 19th-century etching of travelers visiting the Acropolis. As I sit with the president of the museum’s board of directors, Dimitris Pandermalis, we discuss the similarity.

Right from the start, everything seems to indicate that the head of Greece’s most famous museum is not your typical administrator: the sheep on his tie, the first few breaks in the interview when he takes me to different exhibits in the museum to show me exactly what he’s talking about, his candid responses, and even his choice of the museum’s restaurant as the venue for our interview. “I’m not an office person, I’m a museum person,” he confides. “When I stay in the office, I feel cut off; it makes me feel insecure.”

A professor at the Aristotle University of Thessaloniki and an archaeologist for 48 years at the site of the ancient city and sanctuary of Zeus in Dion, he is a man of action and fieldwork, widely considered to be one of the top classical archaeologists in Greece. It was he who, following 35 years of studies, surveys and reports and 140 separate appearances in court to argue the case for this monumental construction project, managed to turn a collective dream into a reality, opening the Acropolis Museum. Under his guidance, it has quickly become a public favorite; in just the first eight years of operation, approximately 10 million people have already passed through its doors.

The base of the building appears to float over the site of an archaeological dig. During the museum’s construction, artifacts were uncovered (ca. 5th century BC to 7th century AD) that shed light on daily life in the ancient neighborhood.

© Nikos Daniilidis

The museum has gained public praise, international awards, and ranks among the world’s greatest: this is an impressive impact. Is it the Acropolis “brand name” that makes it so popular?

Of course, the “brand name” does play its part. The Acropolis summarizes the great moments of ancient civilization. It is a timeless symbol. The Athenians themselves believed that its magnificent buildings could make clear to their allies that they were worthy leaders. But it’s not just a question of marketing. The museum’s exhibits are works of art, great works signed by their creators that represent a specific history and political life which, in essence, shaped the Western world. The visitor has the opportunity to see all of this in a tasteful, modern space.

Why should we visit the museum in person when we can see it all much more easily via our computer screens?

The digital experience, as much as it can create the illusion of three dimensions, can never replace the physical world. If it could, we would have already replaced our whole lives! In the digital world, we follow specifically designed programs. In real life, fundamental roles are played by luck and coincidence. A simple example is that, in the museum, we use natural light. In the morning, the sun’s rays might illuminate one corner, in the afternoon, a different one. The gaze shifts and the protagonists change.

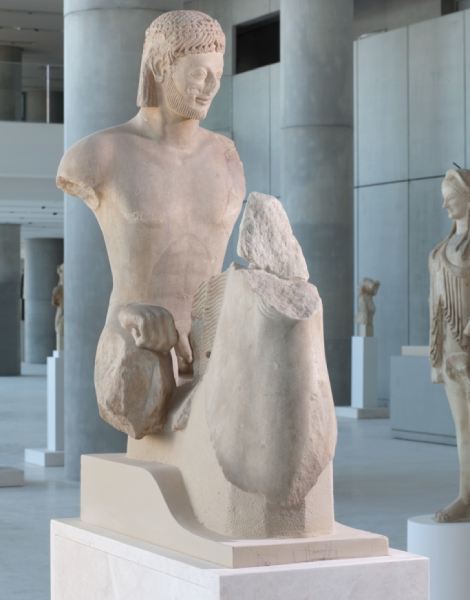

The Rampin Rider

© Acroolis Museum

The original Peplos Kore (ca. 530-525 BC) and a replica painted according to the statue’s original color scheme, as detected by the Acropolis Museum’s Conservation Laboratory.

Say that I am visiting the museum for the first time, and you take me by the hand to give me a tour. What are the things that you tell me I must not miss?

We often hear how, at the Louvre, you must go to see the Mona Lisa or the Nike (Winged Victory) of Samothrace. I am of the view that even if you don’t see them, if you see something else that “speaks” to you, that’s what you need to focus on. People aren’t all alike, we haven’t come out of a machine, and that’s why we try to give visitors to the museum the opportunity to explore and discover things. Those things that are described as “must-sees” don’t exist for us. If it’s something you enjoy, make multiple visits. See one thing and see something else the next time. And I think we’ve achieved our goal with this. A quarter of our visitors have been to the museum at least three times, and there are people who have visited 15-20 times.

Former US President Barack Obama visited the museum shortly before leaving office. Photographs from the tour you gave him went around the world. What did you want to show him?

The prominent people who visit the museum are all very different from one another and, as their guide, I never follow the same route because I try to focus on the things that draw their attention. In President Obama’s case, the protocol was exceptionally strict. Everything was planned down to the minute, right down to the number of steps we would take and where we would stand – we had rehearsed it eight times with the men from his security detail. But when the time came to do it, he was relaxed and continually broke protocol. The pinnacle for me was when we reached the inscriptions of the Erechtheion, which describe the construction of the building. I always show them to visiting officials as a concrete example of democracy – how, for the first time in human history, the disbursement of public funds are recorded. To give him an idea of the salary of an architect, I had in my pocket a replica of an ancient tetradrachm (a coin worth 4 drachmas). They had told me that it was strictly forbidden to touch him or give him anything, but I saw that he was interested and I decided to break the rule. I told him, “I know that I’m not supposed to give you anything, but this is a tetradrachm.” He held out his hand and took it.

In the Archaic Acropolis Gallery, visitors can see all sides of the free-standing sculptures in order to better appreciate their craftsmanship and beauty.

© Vangelis Zavos

Are there any exhibits with which you have developed a more personal relationship?

I like variety in life and in art. Even something that is distasteful to someone forms part of this variety. As such, at least ideologically, it would be odd for there to be something that I like more than the rest. What I can tell you is that, these days, I feel close to the ancient kores. The artist took a piece of marble and, from this formless block, created a masterpiece of incredible technical skill, perhaps of perfection – especially if one thinks of the tools that he had in his hands. And then you come along today and gaze at it, and the most enthralling thing to do is to follow the artists’ process, to think, in other words, of how he created it. What moved him to make something so beautiful, to hone the curves, the subtle differentiations and the imperceptible movement. That’s when you feel the fourth dimension of life, that you can communicate, even if only rudimentarily, with a soul that lived 2,500 years ago.

Is the museum evolving?

Of course. It is the museum’s duty to research and to disseminate to the public the results of its scientific research. For example, there has been in recent years intense interest in the colors of the ancient statues. We have a very rich collection of artworks from antiquity that have many traces of color. We’re acquiring equipment that can decode the ancient colors so we can understand how the ancients perceived them and selected them. We can then choose certain works and create both physical replicas and digital reconstructions. The result is another work entirely. The world as we know it is changing!

This sculpture of a cavalry commander (hipparchos) trying to control his startled horse is believed by many scholars to have been created by Phidias himself. The work forms part of the Parthenon Frieze, many sections of which were appropriated and carried away by Lord Elgin and are now on display in the British Museum.

© Shutterstock

Can you share with us some visitor comments that made you rethink the choices you’ve made at the museum?

People often ask for more information and reconstructions that will help them develop a more comprehensive understanding of the exhibits they are seeing. But at the same time, the museum has a duty to preserve authenticity. My concern is where this dilemma between authenticity and reconstructions will take us. If digital reconstructions end up becoming more engaging to the public than the exhibits themselves, they will do those exhibits a disservice. We make a great effort to find the right balance between the two. On the level with the Parthenon’s frieze, for example, we’ve put the digital projection of the reconstruction right down on the floor.

Does archaeology have value today?

I think it does, particularly in a country like Greece, where antiquities are part of everything – both history and daily life. Every step you take in the city, you see monuments that make you think of another dimension of things. I feel personally responsible when people see ancient sites and say: “These are just some old rocks.” I feel that we haven’t done our jobs properly as archaeologists.

Professor Dimitris Pandermalis spent nearly 50 years supervising excavations at the ancient Macedonian city of Dion, in northeast Greece.

© InTime News

Is the fact that many of the Parthenon Sculptures are located in London an open wound for the museum?

It’s a 200-year-old problem. It’s not just that Elgin didn’t have permission to remove the marbles, it’s that, in removing them so violently, he perpetrated a cultural crime. When you visit the museum, you’ll see that at times we’re verging on the absurd. For instance, we have the head and tail of a horse in this museum, while the horse’s body is in the British Museum. We have the bottom half of a warrior in Athens and the top half in London. It’s something that’s happened, yes, but it’s possible for history to be restored, too, and for there to be a solution.

Ιs there a solution?

To return the sculptures to their home, and for there to be temporary exhibitions to be organized that would be in the interests of both sides. The argument that the British Museum is a global museum that exhibits the sculptures in order to represent ancient Greece is a pretense. They have in their possession the entire frieze from the Temple of Apollo in Bassae, which is from the same period.

What is the next major goal?

For our visitors to discover the ancient neighborhood of the museum, with its streets, houses, baths, shops and workshops, not just through glass floors as is happening today, but to get up close, to walk among the ruins and to get to see showcases full of the thousands of artifacts their inhabitants left behind.

New research reveals that Greece’s most...

Two centuries of dispute, diplomacy and...

A compact archaeological guide to the...

At 1,160m, Metsovo blends preserved mountain...