The Secrets of Amalias Avenue

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

Migration from Kastellorizo, 1938. Bidding farewell to those

who are leaving on the “Fiume.”

© N.G. Pappas Collection

“Australia will always be my birthplace, but Kastellorizo will always be my home,” Maraya Takoniatis, a student whose ancestors had emigrated to Perth, Australia, in the early 1900s, wrote in the newsletter “Filia” in 2015, after she’d spent some time on the island as part of a student exchange organized by the association “Friends of Kastellorizo.”

For years, the subject of my research has been the Kastellorizians of Australia. For me, Maraya’s phrase sums up how Australia’s Kastellorizians have managed to simultaneously maintain and transform their cultural identity over the past hundred years or so.

My academic relationship with Kastellorizo began long ago, in the mid-1980s, when I started my doctorate on the Kastellorizian community of Perth, and has continued unabated with visits to the island and to Australia and, of course, with constant communication with Kastellorizians at home and abroad.

Besides Perth, there are Kastellorizian communities in other Australian cities, such as Sydney, Melbourne, Brisbane, Adelaide and Darwin. (Each of these has its own, clear personality, but it’s the personality of the Kazzie – “Kazzie” is what Kastellorizians call themselves in Australia – community of Perth that I want to talk about here, since they are the ones my research brought me closest to).

The Kazzies of Australia have a very strong sense of themselves as Kastellorizians, rather than just Greeks. However, they also consider themselves quintessential Greeks and quintessential Australians. There are many reasons that lead them to look at themselves like this, including historical, geopolitical, economic and socio-cultural factors at play.

Embracing modernity: Athanasios Avgoustis and his family proudly displaying their new automobile in Perth in 1915 outside Avgoustis’ oyster saloon.

© Courtesy of Eve Mirmikidis

The inhabitants of Kastellorizo had always relied on trade and other maritime occupations, such as fishing and sponge-diving. During the 19th and early 20th centuries, Kastellorizian trader-captains and merchants transported and traded goods all across the Mediterranean and far into the Black Sea. The island prospered and established trading colonies on the shores of Asia Minor.

The result of all this was a socio-economically stratified society, in which the upper orders possessed power and wealth in the form of houses, clothes and jewelry that reflected

a cosmopolitan lifestyle.

Most Kastellorizians emigrated to Australia during the first three decades of the 20th century, in response to the political and economic problems they faced at the time. Restrictions were growing on the autonomy that the Kastellorizians had been granted by the Ottomans and taxes were increased towards the end of the 19th century. The islanders were also unable to compete with steam ships, and industrially produced substitutes led to the decline of the sponge trade, in which the Kastellorizians were heavily involved.

All this affected the island’s economy, as did the rise of nationalism in Turkey from 1908 onwards, a rise that was part of the birth of nation-states everywhere. In 1913, a revolution took place on Kastellorizo, aimed at uniting the island with Greece; this led to instability and shut off access to Ottoman markets. Thereafter, the history of Kastellorizo is a litany of disasters.

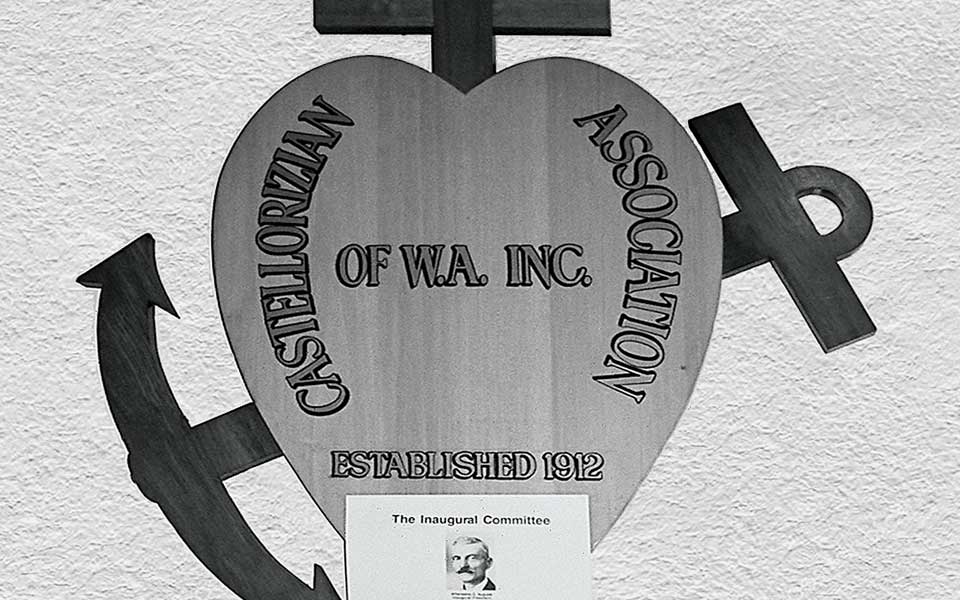

The emblem of Kastellorizo (a heart, an anchor and a cross) with photos of the Inaugural Committee of the Castellorizian Association of Western Australia.

© V. Chryssanthopoulou

The island was occupied by the French from 1915 to 1921, and was calamitously involved in WWI. Between 1910 and 1917 its population dropped by 77%, that is, by 7,000 individuals. The Italians then occupied Kastellorizo from 1921 to 1943, imposing a strict policy of Italianization after 1933. Such was the flight from the island, that from 1936 to 1941 there were only 1,100 inhabitants left on Kastellorizo, as the migrants sailed off to join their relatives and friends in Perth and elsewhere.

During my fieldwork, I talked to Kastellorizians who recalled the melancholy spectacle of emigrant ships leaving Kastellorizo harbor, sent off with songs sung by the womenfolk of the island on the subject of emigration and departure.

During WWII, Kastellorizo suffered terribly. Used as a base by the British, it was bombed and looted. Its inhabitants were moved, first to Cyprus and then to camps in Palestine, until the end of the war. A group of 500 Kastellorizians who’d been in the camps set sail from Port Said in 1945 on the “SS Empire Patrol” to return to their island. The ship caught fire several miles off Port Said and 33 Kastellorizians perished.

Many of the survivors ultimately emigrated to Australia, where they committed their testimonies on their experiences to a digital “site of memory” (www.empirepatrol.com), whose aim is to preserve this material for all Kastellorizians and the general public.

Settling in Australia was easy between 1933 and 1939. All one needed was a deposit of £50 and a relative or friend who could guarantee employment and accommodation. New arrivals provided already-established Kastellorizians with a source of cheap labor, while they themselves benefited from settling close to each other and to the church and community hall, located in Perth’s near-central area of Northbridge, where they lived between the 1930s and 1960s.

Overtime, the bonds between members of the Kazzie community grew even stronger, as they lived and worked side by side. Living and socializing in the same, close-knit area naturally gave the first- and second-generation Kazzies a very strong collective identity.

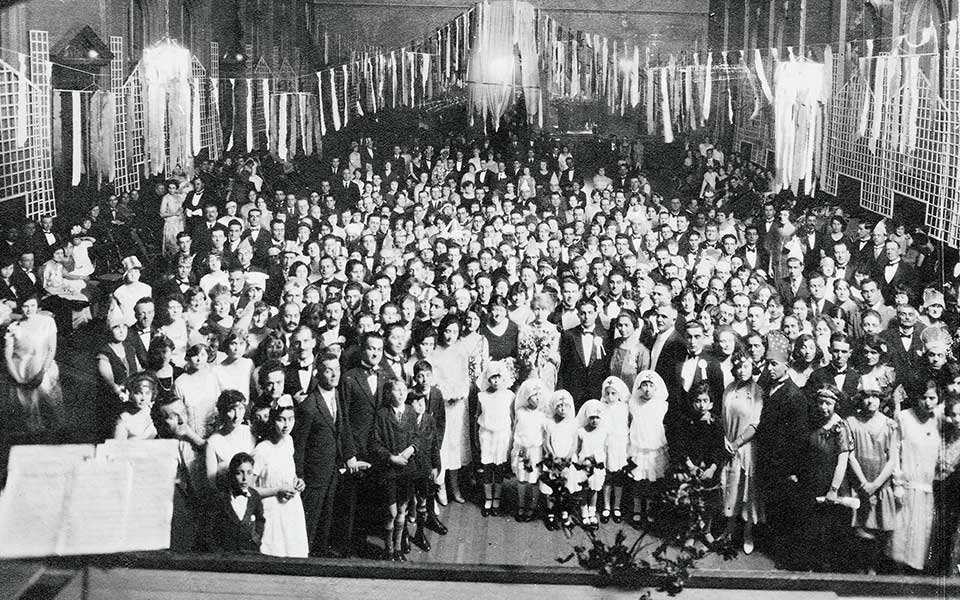

A Kastellorizian Ball, held in Sydney in 1925.

© Vlasios Zanalis Photo Studio "I Filokalia," Castellorizo

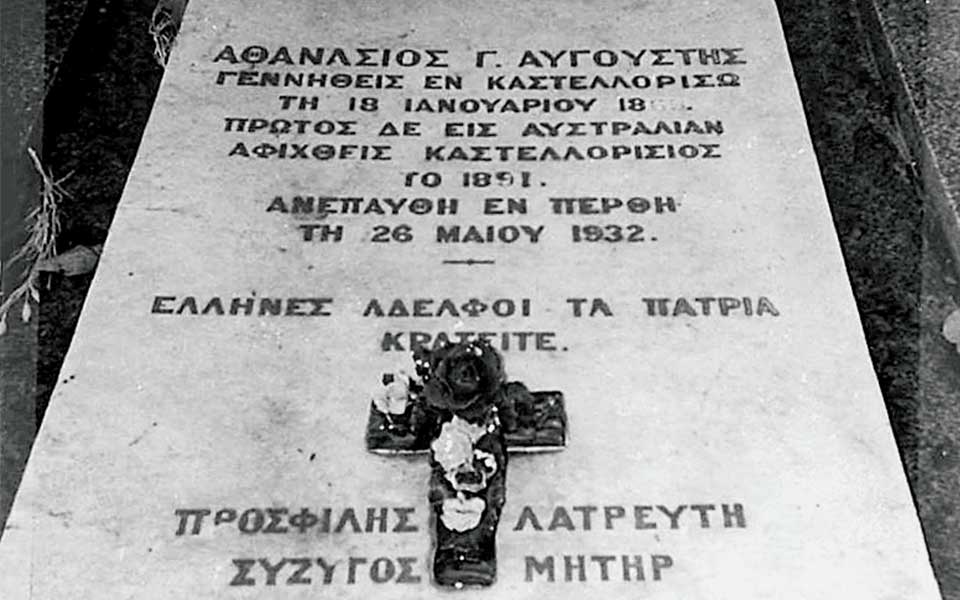

The pioneer who led the chain of migration from Kastellorizo to Perth was Athanasios Avgoustis, or Arthur Auguste, the “safer” anglicized version he chose for himself in Australia. Avgoustis left Kastellorizo when it was still under Turkish rule; in fact, he gave pursuing Turkish authorities the slip as he fled. After traveling to Egypt, he was employed for a time on the Suez Canal, and also held a number of other jobs before journeying to Australia.

In Broome, on the north coast of Western Australia, he worked in the pearl industry. In Adelaide, in South Australia, and in Fremantle, in Western Australia, he cultivated oysters and served them in restaurants he opened there. This career led later immigrants from Kastellorizo to engage in the fishing and fish restaurant industries.

Avgoustis settled in Perth in the mid-1890s and became a leading figure for the Kazzie community, blazing a trail for Kastellorizians (and other Greeks) and showing them how to make a go of settling in a new country.

Avgoustis’ story forms part of the collective Kazzie myth, as it displays all the values, practices and symbols that make up the Kazzies’ view of themselves, or what anthropologists call their “charter of being.”

Greeks of the diaspora will always tell you about the “Greek aptitude for commerce” or the “Greek talent for business.” Unsurprisingly, the Kazzies will tell you this even more forcefully when they talk about the Kazzie community, using the epic of Arthur Auguste to make their point.

The grave of Avgoustis and his wife in the Greek Orthodox sector of Karakatta Cemetery, Perth. The inscription reads “Greek brothers, hold fast to Greek customs.”

© V. Chryssanthopoulou

Avgoustis’ life story includes more elements of “authentic” Kastellorizianness. In 1903, he made the journey from Perth to Egypt to marry a Kastellorizian woman, who returned with him to Australia and gave him a large family.

At that time, Kastellorizians preferred to marry their own, and this they were able to do when Kastellorizian families, including girls and young women, started arriving in Perth in the 1910s. Some early Kastellorizian migrants did, however, marry Anglo-Australian women, and this turned out well, as it raised their public profile in the assimilationist society of the time and helped them negotiate the thickets of Australian bureaucracy.

One such migrant was Peter Michelides, a Kastellorizian from Egypt, who introduced tobacco cultivation to Western Australia, building a tobacco factory in Perth in the 1930s. As time went by, more and more Kastellorizians married “out,” finding either non-Kastellorizian Greeks or non-Greeks. As late as the mid-1980s, though, in all their marriages the Kastellorizians determinedly asserted who they were, symbolically and collectively, by performing Kastellorizian wedding rituals and singing Kastellorizian wedding songs. Now that there are fewer and fewer people left who are able to sing these songs in the traditional fashion, the rituals are handled differently, but they remain important, because they still express the strong bonds of family and community among the Kastellorizians.

The story of Avgoustis is important in other ways for the narrative that Kazzies tell of themselves. Kazzies have always engaged in Greek community politics and have provided political leaders. While I did my fieldwork, I was often proudly told that the Kastellorizians had willingly placed their money and energies at the disposal of the entire Greek community, first and foremost as Greeks and secondarily as Kastellorizians.

Avgoustis and other pioneers set up the Castellorizian Association of Western Australia in 1912, creating the first ethno-regional association in Australia. Acting on behalf of the entire Greek community, this association bought the land on which the Greek Orthodox Church of Saints Constantine and Helen, the patron saints of Kastellorizo, would be built in 1936.

The arrival in Perth of the last wave of Kastellorizian migrants after WWII added another dimension to the Kazzie narrative, stressing the resilience of those who had emerged from war and refugee camps and shipwreck. This epic of survival and dynamism was later publicized in the Australian mass media, thus becoming part of Australian public history.

Hard work and revelry: Greeks from Kastellorizo and Florina relax after a day’s hard work in Innisfail, North Queensland.

© Courtesy of Luke Calopedos

For decades to come, the leadership of the Greek community would be firmly in the hands of Kastellorizian businessmen and professionals. While this confirmed the Kazzies’ belief in their collective superiority and uniqueness, not surprisingly it tended to irritate members of the non-Kastellorizian Greek community, who came from areas such as Greek Macedonia, Crete, the Peloponnese and Lesvos.

From the 1950s to the 1970s, large numbers of Greeks had emigrated to Australia, in response to its open immigration policy, and this had its effects on Kazzie primacy and influence in Perth. New associations were founded and a second Greek Orthodox church was established, to accommodate the new immigrants’ needs for participation and power. At the same time, state ideology shifted from Anglo-oriented assimilationism to multiculturalism, which regarded ethnic cultures as valuable capital, to be cherished and handed down the generations.

This all increased the collective power and self-confidence of Greek immigrants who came to Australia after the 1950s. Official Australian society now valued the Greek language and Greek cultural skills in education and communication, which led to the new immigrants acquiring power in community structures and organizations and, inevitably, to the erosion of positions held by second- and third-generation Kazzies.

Nevertheless, successful Australian-born middle-class businessmen and professionals making up the Kastellorizian elite were and are still promoted as exemplars of core Kazzie values and practices, that is, professional and economic success on the part of the men, commitment to the family, home and the up-bringing of children on the part of women and involvement on the part of all in the community, in charities and above all, in the Church.

When second-generation Kastellorizian civil engineer and academic Ken Michael became Governor of Western Australia (2006-2011), the prestige of this group naturally increased, as did the collective symbolic capital that this group enjoyed in Australia and overseas.

Open for business: brothers Theodosios, Konstandinos and Evangelos Penglis in their newly-opened café in Halifax, North Queensland, 1917.

© N.G. Pappas Collection

By the mid-80s, most Kastellorizians were using the narratives from much older relatives and, of course, their own imagination to link themselves to their ancestral island. The Kazzies had socialized together, holding fast to their values and customs in a tight-knit community over the decades, despite the inevitable trans-formations wrought by time and by living in Australia. The members of the second and third generations were, therefore, deeply attached to their image of their homeland, and the values that Kastellorizian immigrants and their descendants had maintained in Australia made them want to “give back,” as the motto of the “Friends of Kastellorizo,” an association created by Australian-born Kazzies, has it, “to the island of [their] forebears.” And so Australian-born Kastellorizians began to return to Kastellorizo, in the hope of putting down roots in a place where many no longer had any living relatives.

One of the unforeseen consequences was litigation between the Australians and those islanders who had taken over abandoned homes on the island. However, good things also ensued,

with improvements to the infrastructure and the reconstruction of houses, with all the economic benefits this brought. This was when second- and third-generation Australian Kastellorizians took to celebrating their weddings on the island, bringing over friends and family, holding traditional rituals and strengthening the bonds with the ancestral land, in a deeply emotional communion with the Kastellorizians of the past.

Above all, they took it upon themselves to familiarize their own children and grandchildren with the culture and environment of the island. This involved such things as long and expensive trips to Kastellorizo and yearly student exchanges, an experience that left a deep impression on anyone who took part. The young islanders who visited Australia through this program benefited just as much, increasing their knowledge of, and empathy for, their “compatriot others” who live Down Under.

The development of such mutual understanding has led to joint projects, including efforts regarding the protection of the island’s natural environment, which is felt to belong to resident and diaspora Kastellorizians alike. Thus, Kastellorizo now flourishes in both hemispheres, the result of the strong bonds between the two communities, diaspora and resident, providing a good example of the way in which people in today’s globalized world construct enduring transnational identities.

VASSILIKI CHRYSSANTHOPOULOU has a doctorate in Social Anthropology from Oxford University and is an Assistant Professor in the Department of Philology at the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens. Her book, Sites of Memory in Castellorizian Migration and Diaspora (in Greek; Papazissis Publications, Athens 2017) won the Moskovis Dodecanesian Prize of the Municipality of Athens in 2018.

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

In Syntagma Square, marble, flame, and...

On the city’s eastern edge lies...

From historic landmarks to edgy street...