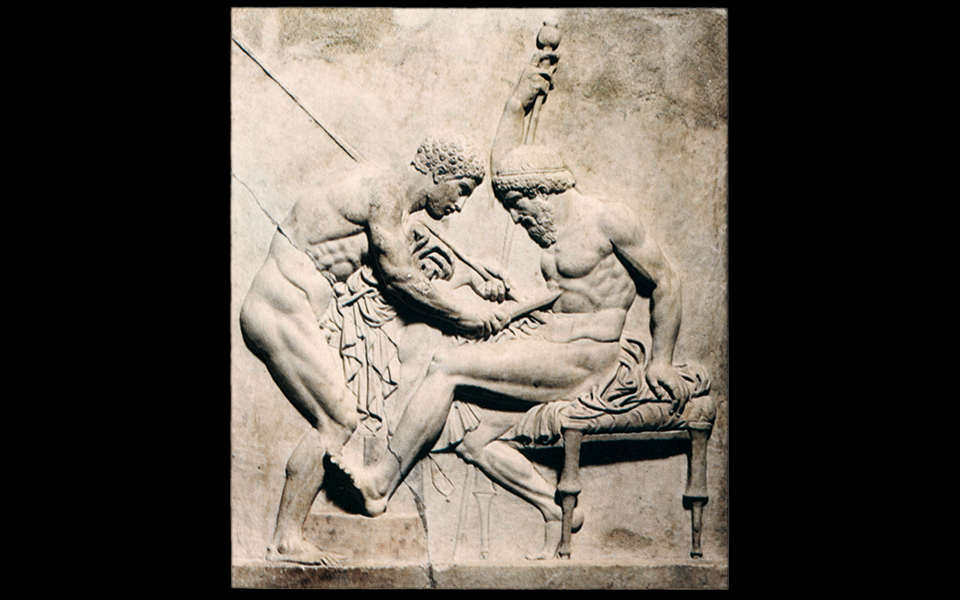

The name Achilles usually conjures up images of the brave warrior who struck terror in the hearts of his enemies. However, one of the best-known depictions of him, on a red-figure kylix by the Sosias Painter, reveals a different side to the hero, showing him just after he has removed an arrow from the left arm of his beloved friend Patroclus as he carefully applies a white bandage to the wound.

There should be nothing surprising about this representation. In the Iliad, Achilles and many other heroes are portrayed as having medical knowledge, especially regarding the treatment of war wounds received in the numerous engagements fought between the Achaeans and Trojans over the years outside the famed walls of Troy. Sthenelus, for example, gives medical aid to Diomedes, the king of Argos, while Patroclus dresses the wounds of Eurypylus using a bitter root with analgesic properties. Some have identified this root as the plant Achillea millefolium, commonly known as yarrow or soldier’s woundwort. The genus name Achillea is in fact derived from the belief that Achilles, too, used this plant to treat the wounds of his comrades-in-arms.

“In the Iliad, Achilles and many other heroes are portrayed as having medical knowledge, especially regarding the treatment of war wounds”

Indeed, invincible Achilles, the greatest champion of the Greeks, reportedly learned much about the use of ‘gentle medicines’ – including the aforesaid root – from Chiron, the wise old Centaur who taught nearly all the celebrated healers of Greek mythology. The Greek expression “He that wounded shall heal” is also associated with the therapeutic practices of Achilles. According to myth, in one particular battle, Achilles speared King Telephus of Mysia in the thigh. The wound festered, prompting Telephus to consult an oracle, who told him that the weapon which caused it would be needed to heal it. So Telephus had Orestes, son of King Agamemnon, kidnapped in order to blackmail Achilles into helping him. The great warrior scraped filings off his spear and applied it to the king’s wound, which subsequently healed. Today, we know from studies published by Canadian scientists that copper filings can create static electricity, which has germicidal properties, on the surface of a wound.

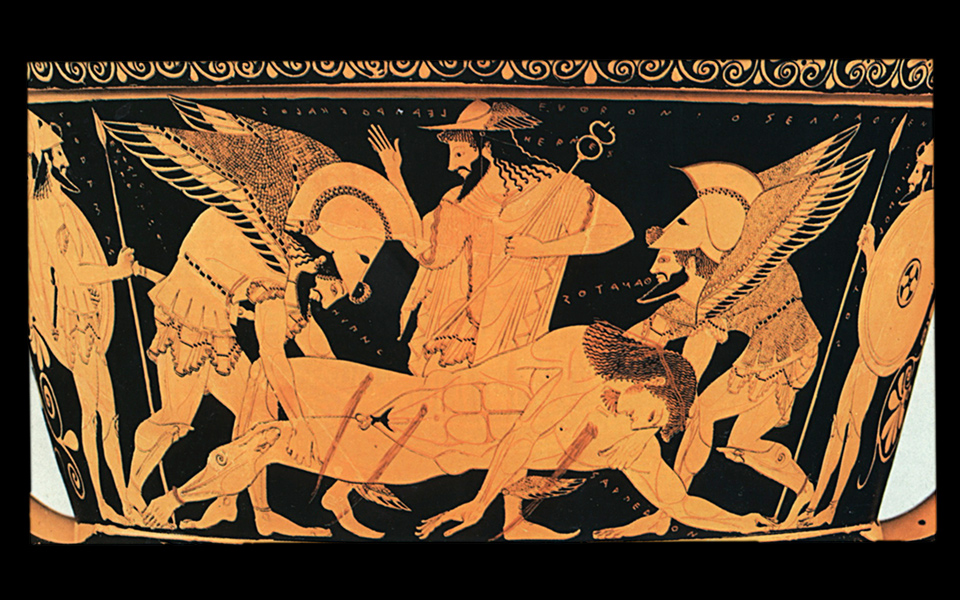

In addition to fighters with medical knowledge, the Iliad also features ‘professional’ physicians. These include two sons of Asclepius, Machaon and Podalirius, the former ‘specializing’ in surgery and the latter in pathology. Both, of course, had gone to war not just to heal but also to take part in combat, leading 30 ships from three cities of Thessaly into battle on the side of the Greeks. Nonetheless, they were so highly valued as physicians that when Machaon was wounded, the Achaeans – including Achilles – were deeply disturbed, for they believed that “a healer like him… is worth a regiment”. Their anxiety was so great that Idomeneus, King of Crete, called out to wise Nestor to immediately take Machaon from the battlefield to the ships, where his wound was treated. A description of Machaon’s medical skills appears in verses 210-219, Book IV of the Iliad, when he treats King Menelaus of Sparta, husband of Helen, by first removing an arrow from his chest and drawing blood from the wound (so that no venom might enter his body) before applying a healing salve to the wound.

“In addition to fighters with medical knowledge, the Iliad also features ‘professional’ physicians.”

© Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York

This is not the only detailed medical description that Homer gives us. In addition to frequent references to mental disorders (including mania, delirium and depression), which are usually – though not always – suffered by the gods rather than mortals , the verses of the Iliad contain 147 descriptions of physical wounds and injuries to different parts of the body, caused by the weapons of the time (spear, sword, arrow), which underscore its characterization as a war epic. The great poet also provides some remarkable anatomical descriptions. In the Iliad and the Odyssey, there are approximately 150 anatomical references, describing different parts of the human body with terminology still in use today, such as auchenas (nape of neck), ischio (hip), pneumonas (lung) and krotafos (temple).

Homer’s descriptions of wounds and treatments are so realistic, and his medical terminology so rich, that some maintain he himself may have been a physician, or that he came from a medical family or had close ties with some healer. But this does not appear to be the case. These detailed accounts can perhaps be better explained by his poetic prowess and extensive learning rather than by medical training as such. Whatever the truth, the wealth of data in the references is such that the Iliad and the Odyssey serve as the earliest source of information we have about Greek medicine.

“The wealth of data in the references is such that the Iliad and the Odyssey serve as the earliest source of information we have about Greek medicine.”

Bearing in mind that these epics were written in the 8th century BC, while the Trojan War itself had taken place several centuries earlier (late 13th-early 12th century BC), it is clear that the medicine to which Homer is chiefly referring is not that of this earlier period but of his own era. Furthermore, it is not exactly science-based medicine in the sense of what developed later with Hippocrates (460-370 BC), but rather a healing art based on the experience and skill of its practitioners, involving both ‘surgical’ procedures and pharmacology. Despite this, however, it has a rational basis and cannot be likened to ‘magical’ or theurgic medicine and mystical practices, even though there are descriptions of such in Homer as well, passages which attribute illnesses or their cure to divine intervention. The most characteristic example of these is found in the very first book of the Iliad, where Apollo, enraged because his priest Chryses has been dishonored by Agamemnon, sends an “evil plague” that decimates the men and livestock of the Achaeans.

Regarding the ‘surgical’ procedures described by Homer, these obviously referred to the tending of wounds in the sense that they were first cleansed, washed with tepid water, treated with palliative and antiseptic herbs, and finally bandaged. As for the ‘medicines’, these were primarily herbs used to relieve pain and other pathological symptoms of both body and mind. Wines and certain infusions were also used to help the healing process. Helen of Troy, the cause of the war between the Achaeans and the Trojans, knew of an effective soothing herb that alleviated pain and anger and brought forgetfulness of every sorrow when mixed with wine. We do not know if she herself used it when the Achaeans captured Troy, but we do know – from Homer – that she later gave it to Telemachus, son of Odysseus, to relieve the grief caused by the continued absence of his father, the resourceful king of Ithaca.

“As for the ‘medicines’, these were primarily herbs used to relieve pain and other pathological symptoms of both body and mind.”