Many Greeks regard the popular rebetiko song “Synefiasmeni Kyriaki” (“Cloudy Sunday”), written in Thessaloniki by folk composer and singer Vassilis Tsitsanis (1915-1984) during the German occupation in WWII, as a sort of unofficial national anthem. This song, which enjoyed record sales when it was first released as a single, has been covered by myriad singers and recorded again and again, not only in Greece but in the USA, Canada and Australia as well.

It was first recorded during the brutal winter of 1943, when the as-yet-unknown Tsitsanis was performing with an ensemble at a small ouzeri that had opened at 22 Pavlou Mela Street in downtown Thessaloniki. Rumor has it that, as he was returning home late one night, Tsitsanis saw a German patrol kill a young man in cold blood. Years later, he told researcher Costas Hadzidoulis: “My heart bled at the sight of the dead lad and I, in turn, wrote a bloodied song.”

The original title, in fact, was “Bloody Sunday,” but he changed it over fears of censorship from the German authorities. This precaution proved successful. According to the testimonies of patrons who frequented the ouzeri at that time, officers of the Wehrmacht could often be seen sitting at the establishment’s best tables, enjoying Tsitsanis’ music in blissful ignorance of the meaning of his lyrics.

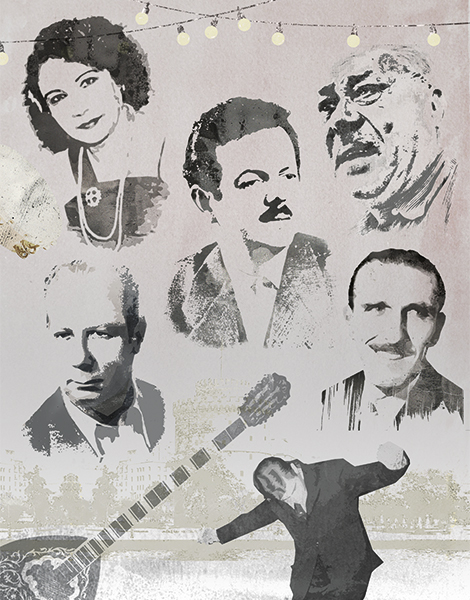

That Thessaloniki owes its rebetiko reputation to Vassilis Tsitsanis is an indisputable fact. Before him, the preference was for the demotic music, the plaintive laments and the Anatolian airs so beautifully performed by the Jewish-Greek diva Roza Eskenazi.

Like the Argentinean tango and the American blues, rebetiko was born in the early 20th century in the slums; it came to be identified with the hundreds of thousands of refugees who arrived from Asia Minor in 1922, bringing with them the music of the Greeks in that region.

© Κostas Ηatzidoulis Archive

The genre evolved during the 1930s, when its themes were expanded to include themes beyond heartbreak, passions, prison, disdain for the law, nostalgia for the homeland, the trials of the refugees and the tribulations of the working man. Likewise, the ensembles were also gradually enriched beyond the three main instruments – bouzouki, guitar and baglama – with the addition of the accordion, violin and tzoura.

THE ARRIVAL OF TSITSANIS

Vassilis Tsitsanis did his military service from 1938 to 1940 in the Telegraphists’ Regiment, whose headquarters were located in the service areas of the famed Alatini Villa (today home to the Thessaloniki Regional Authority). It was in Thessaloniki that he met and married his wife, Zoe Samara, and it was here, too, that the war found him in October of 1940.

He stayed in the city for nearly a decade, writing over 70 songs (every anthology of rebetiko music has songs by Tsitsanis) and performing with his band at his own ouzeri or at one-off appearances at some of the most popular nightclubs of the time.

Tsitsanis’ singing was also the stuff of legend. Unembellished, even abstract to some, “with a heart-wrenching staccato style that cut phrases like a sob,” according to musicologist Giorgos Leotsakos, he established a new way of performing that was more “western” than “eastern”. What’s more, he worked hard to rid the music of its seedy connotations.

“I did not try to give a political tone to my songs,” he said. “Simple situations, sad and happy moments, pain, poverty and the trials of the unfortunate are the subject of my songs that struck a chord with people.”

The new Rebetiko joints

If you’re interested in hearing authentic rebetiko performed live as it was in the good old days, unembellished and unplugged, the experts on Thessaloniki’s music scene recommend the following places:

- Alambra (80-82 Filippon)

- Tobourlika on Navarino Square (5 Vyronos)

- Rossignol in Ano Poli

- Pringipessa on Tsiroyianni Square (5 Filikis Eterias)

In addition to giving us a wealth of unrivaled music, Tsitsanis also cultivated an entire generation of young musicians, developing the “Thessaloniki School” of rebetiko.

Musicians such as Takis Binis, Apostolos Kaldaras, Prodromos Tsaousakis, Babis Bakalis and Manolis Hiotis, as well as vocalists Stella Haskil and Sevas Hanoum (the stage name of Sevasti Papadopoulou) all first appeared by his side before going on to make history of their own in the postwar era.

Tsitsanis also influenced the evolution of the Greek “entechno” musical genre. Greats like Manos Hadjidakis and Mikis Theodorakis were among his fans and would always present themselves as “his humble students.”

From 1946 onwards, Tsitsanis pursued his career in Athens, while a few members of his ensemble emigrated to America because of the Civil War. In the US in particular, rebetiko had already been embraced as “the Greek blues” and most of the classic rebetiko songs had been recorded again in new executions.

Info

Tasos Papadopoulos, a guide for the Thessaloniki Walking Tours group, specializes in explaining how specific locations in the city are connected with the music, bringing the fascinating story of rebetiko to life with his narrative.

Every Sunday morning, he takes participants to sights that include the old prisons at Yedi Kule and the minaret of the Rotunda, revealing along the way the places and stories that feature in famous rebetiko songs, as well as the sources of inspiration and the hangouts of these special musicians. For more information call (+30) 697.818.6900-1. (Participation costs €15).

© Perikles Merakos

© Krina Vrondi

THE NIGHTCLUBS

The different rebetiko bands that formed in Thessaloniki between 1938 and 1948, either with or without Tsitsanis, breathed new life into the city’s nightclub scene and led to the opening of several new establishments, with more tables, bigger stages for the musicians and a new emphasis on the menu to attract patrons.

Some of these Thessaloniki clubs became the talk of the country: these included Koutsoura, owned by Giorgis Dalamangas; the kafeneio Astoreia; and the more sophisticated clubs such as Mimosa, Folia, Aetos, Kipos, To Papafi – where Markos Vamvakaris appeared for a season – and Barbalias in Karabournaki.

The classic rebetiko joint was small, with 10 or 15 tables at best, and a small wooden stage at one end with three chairs for the musicians. There were no microphones or proper restaurant service. Food was limited to simple meze served to accompany ouzo or sweet Mavrodafni wine.

The program would begin at 9pm and end at midnight, when the public curfew took effect. After going over their repertory, the musicians would then perform requests made by customers who would, if they had the nerve, also dance alone in front of the small stage.

Of course, the rebetiko music that flourished in the hash dens before the war was still performed in seedy basements around the port, where the city’s thugs, jailbirds and criminals hung out. Several of these underground types collaborated with the Nazis, including the notorious figure known as Kerkyras, who owned a taverna at Vardaris and – according to poet Dinos Christianopoulos in a study he wrote on rebetiko – participated in the execution of patriots. Kerkyras was eventually murdered in 1944, right at the entrance of his taverna.

None of these clubs or tavernas exist today, unfortunately, but Thessaloniki does still have a number of musicians who are trying to keep the rebetiko tradition alive in new establishments.