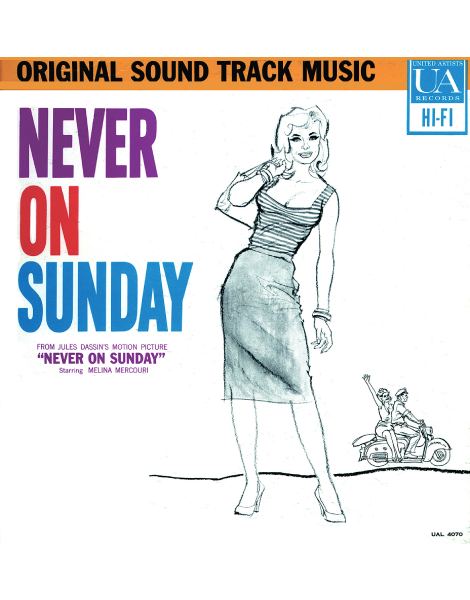

Νo one could have imagined that the formal reception to mark the screening of the movie “Never on Sunday” at the Cannes Film Festival in 1960 would turn into a joyous Greek party. And yet, on that warm spring evening, that’s exactly what happened, as dozens of festival guests danced until dawn around Jules Dassin’s leading lady, Melina Mercouri, to the music of Manos Hadjidakis, accompanied by George Zampetas on the bouzouki.

The following year, Hadjidakis went on to win the Academy Award for Best Original Song for the film’s rousing theme tune “Ta Pedia tou Pirea.” Nana Mouskouri was already singing it all over Europe, while acclaimed jazz musicians Duke Ellington and Dizzy Gillespie and celebrated female singers such as Lena Horne and Eartha Kitt would help make the English version, “Never on Sunday,” one of the most frequently-covered songs of the 20th century. Above all, though, the movie served to make Greece itself fashionable, cementing the country’s reputation as the proud homeland of Mediterranean bonhomie and optimism.

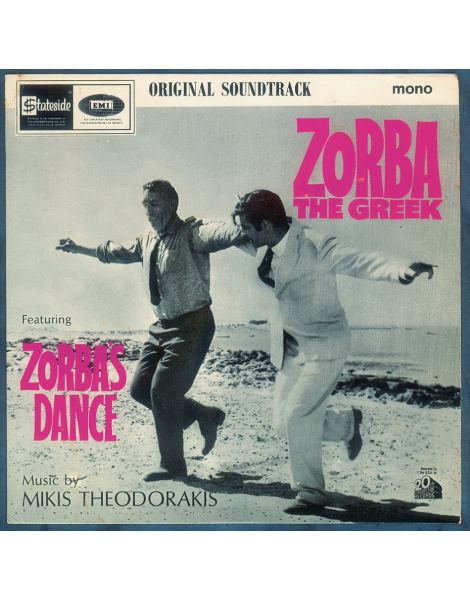

A few years later, in 1964, on a sun-drenched beach in that same charmed nation, Anthony Quinn and Alan Bates danced to the music of another Greek composer, Mikis Theodorakis, in a stand-out scene from another award-winning film, “Zorba the Greek,” directed by Michael Cacoyannis. From Connie Francis and Dalida to the Prague Philharmonic Orchestra and Maurice Béjart, countless artists and ensembles reinterpreted the composition as everything from a playful ditty to an orchestral work and ballet. Greek music had become famous in its most authentic form, sustained by the life-giving force of folk tradition.

However, even among those who have hummed the tune of “Never on Sunday” or danced syrtaki to the tune of “Zorba the Greek,” very few are aware that Hadjidakis and Theodorakis worked on numerous international scores that drew far less on Greek tradition.

© Mikis Theodorakis Archive

© Mikis Theodorakis Archive

Already by 1956, Theodorakis was working on his first collaboration with Michael Powell, writing the music for the Powell and Pressburger film “Ill Met by Moonlight,” also known as “Night Ambush.” It was at this time that this dedicated left-wing activist had a chance encounter with Arthur Miller, outside the studio restroom. Miller was waiting for his wife, Marilyn Monroe, during a break in shooting for “The Prince and the Showgirl,” which had begun in an adjacent set. Theodorakis later described Marilyn as “very polite and very cute; she looked like a Russian peasant girl in a headscarf.”

But it was thanks to another film by Powell, “Honeymoon” (1959), that Mikis (as he is affectionately known among Greeks) first saw one of his numbers, the film’s title song, become a hit in Europe and the USA. It was such a hit, in fact, that the Beatles covered it during a live BBC radio program in 1963.

A few years later in Paris, under the direction of Theodorakis, Édith Piaf would sing about the tragic tale of love that unfolds in “Les Amants de Teruel” (1962), while in the same year, in Dassin’s film “Phaedra,” Mercouri would sing the composer’s “I Gave You Rose Water” to the love-struck Anthony Perkins (telling him, mournfully, that: “like all Greek songs, [it’s] about love and death”).

© Manos Hadjidakis Archive

© Manos Hadjidakis Archive

The Greek military junta was unable to prevent the spread of Theodorakis’ music, at least outside of Greece. Despite living under house arrest at Zatouna in the Peloponnese, Theodorakis still managed to communicate his approval to Costa-Gavras for his works to be used as the soundtrack for “Z” (1969). The film received a number of awards, including an Oscar for Best Foreign Language Film, the Jury Prize at Cannes, and a BAFTA for Best Film Music.

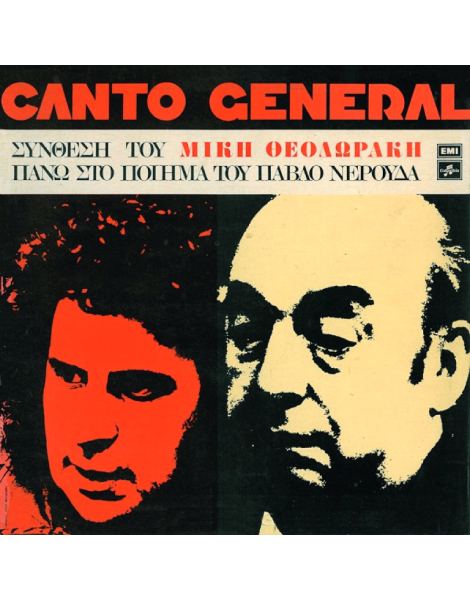

When Theodorakis was finally allowed to go into exile in Paris, he started work on the music for “State of Siege” (1972). For this soundtrack, Theodorakis drew on elements of Latin American music, and he’d later use the same melodies in “Canto General,” an oratorio based on poems by Pablo Neruda, which thrilled audiences all over the world. Theodorakis also composed the original score for Sidney Lumet’s “Serpico” (1973), which he wrote during flights between concert tour venues and which features several haunting jazz-infused pieces.

The Mediterranean DNA of Mikis’ compositions has never limited their universal appeal. This is most clearly illustrated by the fact that they have been performed in different languages and in varying styles by artists as diverse as America’s Joan Baez, Wales’ Shirley Bassey, Puerto Rico’s José Feliciano, Majorca’s Maria del Mar Bonet and Italy’s Al Bano, not to mention Swedish choirs and German orchestras.

Like the music of Theodorakis, Hadjidakis’ music has also shown itself to be highly adaptable. Indeed, his “All Alone Am I,” popularized by Brenda Lee, even received a country music award. However, the composer himself didn’t approve of many other versions of his songs – particularly of “Never on Sunday” – dismissing them as “repackaged folklore.” It should also be noted that he didn’t turn up at the 1961 Oscar ceremony to accept his award. (“Never Happened Before,” exclaimed the headline of one US newspaper, in a playful nod to the title of the winning film).

Many acclaimed singers, including America’s Nat King Cole, Germany’s Lale Andersen, Israel’s Ofra Haza and Portugal’s Amalia Rodrigues, have performed his compositions most admirably in other languages. Among them was also Marie Bell, whom Hadjidakis first saw singing a bittersweet song on the screen of a local cinema in Athens when he was just thirteen. He couldn’t have imagined back then that one day he’d be writing music for the famed French actress. When this finally happened in 1961 when they worked together on the play “La Voleuse De Londres,” Hadjidakis had the opportunity to confess his adolescent love and dance to that same tune with her at her home on the Avenue des Champs-Élysées.

In the wake of his success at the Oscars, many international adaptations of Hadjidakis’ works were recorded without his involvement, while he himself focused on more creative projects. In 1962, he wrote the soundtrack for Elia Kazan’s “America America,” which featured the santouri rather than the bouzouki. Hadjidakis didn’t want it to sound too much like “Ta Pedia tou Pirea,” believing that Dassin’s film had contributed not only to the “industrialization” of Greece’s tourism but also to a “commodification of its quaintness.”

© Manos Hadjidakis Archive

© Mikis Theodorakis Archive

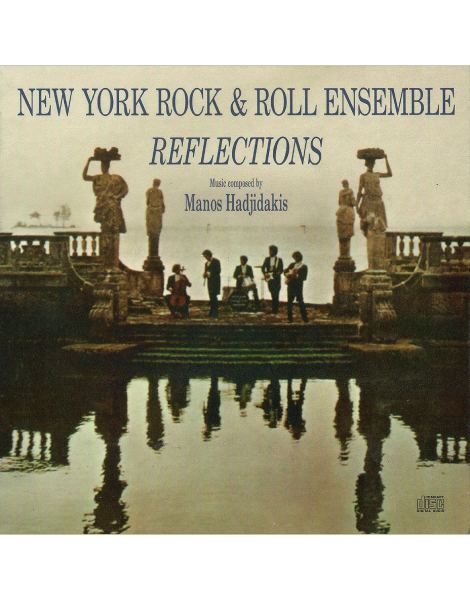

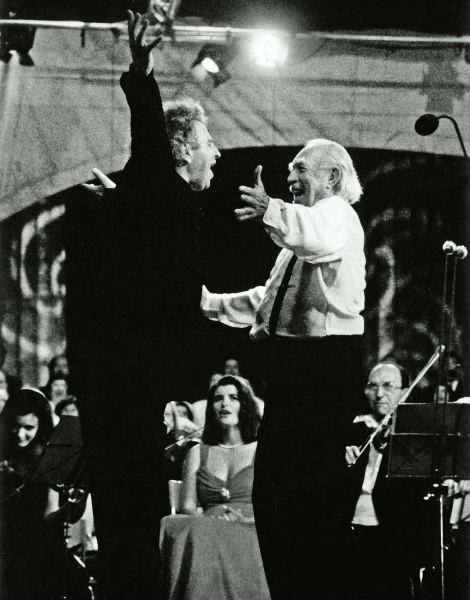

By this time Hadjidakis was living in the USA. Here he wrote the music for the “poetic” western “Blue,” starring Terence Stamp. When he wasn’t recording with the Los Angeles Symphony Orchestra, he was being photographed with the Bee Gees or dining with Leonard Bernstein. The orchestral “Gioconda’s Smile” (1965), as well as “Reflections” (1970) – which was performed by the New York Rock & Roll Ensemble and which has been described as classical baroque rock – were both products of that fertile period of new ideas and ambitious projects. Among the latter was a film version of the musical “Street of Dreams,” with English lyrics by John Lennon.

Hadjidakis returned to Athens in 1972, just before the collapse of the junta, while Theodorakis returned immediately after the event. Although their international exile was over, the music of these two Greek artists – now infused with contemporary influences – remained popular and much-admired among respected foreign artists. In 1974, Hadjidakis composed the soundtrack for the avant-garde “Sweet Movie,” directed by Dušan Makavejev. Two of the songs from the film captivated Pier Paolo Pasolini, who wrote lyrics for them in Italian. In 1977, the composer’s music framed the exciting journey of Jacques Cousteau in “Calypso’s Search for Atlantis.” After the death of his close friend Nino Rota, Hadjidakis received a collaboration proposal from Federico Fellini, but he declined, instead recommending Nicola Piovani.

Decades passed and fashions changed, but opera divas such as Angela Gheorghiu, along with acclaimed musical groups and rock bands, including Pink Martini and The Walkabouts, continued to rediscover and perform the songs of Greece’s two most outstanding composers. “All Alone Am I” has even been recorded in Zulu by the South African singers Stella Khumano and Faith Kouyate, while the hardcore American hip hop group Black Moon has even rapped Hadjidakis’ songs. And why not? It wasn’t long ago that Theodorakis was singing one of his pieces alongside German composer Rainer Kirchmann in a version that can only be described as electric rock!