Walking the Peloponnese: 12 Trails, 1,700 Kilometers

Greece Is presents "Peloponnese Trails," a...

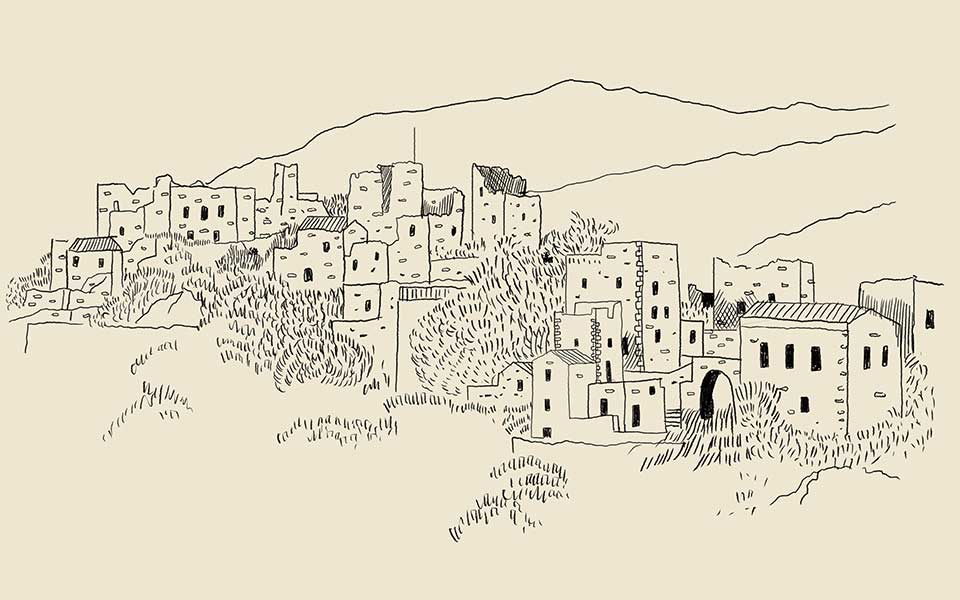

© Illustration: Philippos Avramides

Lying quietly at the southern ends of Europe, Mani is one of those real socio-historical fragments that the sophisticated visitor appreciates and enjoys.

Centered around the famous Taygetos mountain range that terminates in the steep sea cliffs and deep inlets of Cape Taenaron (Matapás), Mani of the Southern Peloponnese is a mosaic of small and large villages located in short distances throughout the Laconia and Messinia regions. To locals, Laconian Mani is traditionally known as Inner Mani and is distinguished from Outer Mani, its Messinian counterpart. The traditional village street plan resembles urban labyrinths: complex, narrow alleyways that divide the village into neighborhood enclaves formed around one or more tall war towers and/or shorter towerhouses.

The Maniats became known from the 17th century onward, on the one hand, for their piracy, brigandage, and rebellions against the Turkish state during the Ottoman occupation, and on the other hand, for the women’s improvised poetry, the laments, composed in elaborate death rituals. There are differences in the form, content and performance of the latter between Inner and Outer Mani.

Maniat laments (moirolóyia) have attracted considerable attention by various scholars and visual artists who have appreciated and interpreted these elaborate compositions mainly as poetic expressions, as psychological acts of creation, and/or as a relief from pain and loss. Regarding their performance, some local historians also claim a direct continuity with ancient Greek tragedy.

Yet, a long term fieldwork in the area and participation in women’s rituals, provides a deeper understanding of that unique culture and its practices.

As the basic anthropological tenet goes, before we narrate stories about other cultures and ways of life, we have to learn how the members of those cultures narrate their own stories. Put differently, we have to learn how people claim their truth.

© Illustration: Philippos Avramides

*

Maniat women move discreetly and swiftly in their towers and through the narrow streets between towers. They move close to walls and avoid public spaces defined as male. They emerge from the low entrances and exits of their tower-houses…only to bend again over a rocky terrain during agricultural work, over an open or covered grave in the cemetery…When the “whisper” of death comes, these bent women, creatures of the back alleys, stand up. They scratch their upper body and throw the head back, pulling out their loosened hair. They raise fists against the sky, beating their chests in anger, scratching their faces, screaming. It is then that one sees Maniat women in their full height.

Hey, you God, from high above

Where the gun can’t reach you!

Why don’t you descend below

To talk about rights?

We have the most [rights]

For we are left without child… (lament exerpt)

*

Each woman who emerges from the collectivity of female mourners during the mourning ritual is the soloist in pain. The rest of the women, the chorus, validate or invalidate her pain and discourse by generating antiphonic responses, linguistic and bodily. In that world, discoursed pain and discourse in pain constitutes truth.

The true discourse will be then disseminated beyond the ceremony as oral history. The mourning ritual, thus, is far from a discourse of the moment or of the present, as it is said of ancient tragedy, but it constructs memory. It is the central site for the production and reproduction of contrasting views and of gendered logos through the dialogical technique of antiphony. This is how those women, the oral historians of the area, claim truth with memory and pain. There pain is not to be eliminated ‑ as it is in our Western model of therapeutic catharsis‑ but to be endured as a labor task.

In Greek, the concept of antiphony (antifónisi) possesses a social and juridical sense in addition to its aesthetic, musical, and dramaturgical uses. Antiphony can refer to the construction of contractual agreement, the creation of a symphony by opposing voices. It also implies echo, response, and guarantee. In Greek, the prefix anti‑ does not only refer to opposition and antagonism but also equivalence, “in place of,” reciprocity, face‑to‑face. These meanings are embedded in the vocabulary of laments.

© Illustration: Philippos Avramides

Mourners in their laments claim to “come out as representative” (na vgho antiprósopos) of the dead (prósopo means face or person, and antiprósopos means representative). Related and emotionally laden phrases are “to witness, suffer for,” “to reveal the truth about,” and “to come out as representative for” (na martiriso) the absent other, the dead. Antiphony or dialogics, thus, is not simply a dialogue with an external other, as we understand dialogue today, but also a dialogue with an internalized other, be that human or non human other.

In order to claim her right to come out as representative, the mourner has to establish a shared substance with the dead; that is, recount past commensal events. There have never been paid mourners in Inner Mani, as they were in ancient Greece: paid mourning does not require shared substance as an exchange of emotions. In Mani, “Tears shed without a common history of reciprocity are matter out of place.” (Seremetakis, The Last Word, p. 216).

To “witness,” and “to come out as representative for” are narrative devices in laments that fuse jural notions of reciprocity and truth claiming with the emotional nuances of pain. Pain, in other words, to be rendered valid and true had to be socially constructed through antiphonic relations. Lament singers claim that they cannot attain the proper emotional intensity and reality outside of this antiphonic structure and thus outside of the ritual itself. Antiphonic performance entails both the declarations of the soloist and the repetition, response and historicization of the latter’s discourse by the chorus. To hear a lament improvised is not to merely hear one person sing, but to hear an entire social ensemble vocalize. (Seremetakis, The Last Word, p.120)

© Illustration: Philippos Avramides

Maniat women thus historicize from the position of death, which means historicizing at the limits of the inside, from a site of absence and the without. They use marginalized and heterotopic memory of shared substance and reciprocity to challenge the public order of space itself. Their mourning ritual is far from being just an expressive discourse; it has an interventionist role in society. Like Antigone in ancient tragedy, Maniat women have to decide between two conflicting laws, the one required by the state and patriarchy, and the other required by shared substance and emotional reciprocity. Antigone’s law too, transcended death and forgetfulness brought by absence, and stood against the law of the powerful king Creon when he and the Polis barred her brother’s body from burial and implicitly from the city.

The centrality of shared substance, reciprocity, and care and tending ethics in women’s discourse extends beyond the ritual; through these ethics they weave together their everyday practices into a single experiential continuum: household chores, burying and unburying the dead, lamenting, dreaming and dream interpretation, and the imprinting of their labor on agricultural space, as mnemic space. This is the poetics of the periphery—for the social imaginary of the periphery is always a material culture. Poetry (poesis) in Greek means both making and imagining. Sensory memory is encapsulated and stored in artifacts, spaces, and temporalities of both “making and imagining,” of sharing and exchange. As Diotima has responded to Socrates: “Any action which is the cause of something to emerge from non existence to existence is poesis, thus all craft works are kinds of poesis, and their creators are all poets. … Yet, they are not called, as you know, poets, but have different names …” (Plato, Symposium). The part has taken the name of the whole.

Modernity has brought paradigmatic shifts in the social construction of reciprocity, truth and memory. The “archaeology” of emotions has been marginalized and displaced by the literal economies of exchange. The subordination of Maniat women today is expressed in the dismemberment of the archaeology of emotions as a historicizing discourse. It is the reduction of feeling to a psychological condition.

Lamentation is dying out in the epoch of literality and as pain and death are becoming part of medical and economic establishments, the displacement of local memory becomes a visible threat.

Yet, the Maniat war towers still stand erect to remind us, like “epigraphic witnesses,” that real historical models such as the Maniat culture are more precious now than ever. They inspire alternative views of life and death, of remembering and feeling, and propel us to a self-reflexive dialogue on what constitutes the human now.

Greece Is presents "Peloponnese Trails," a...

From ancient healing sanctuaries to legendary...

From epic battles to avant-garde tragedy,...

A historic hotel redefines modern Greek...