Feta, Tsipouro, Sausage… and Off We Go to...

Three traditional products serve as both...

The village of Plomari in Lesvos is particularly tied to the production of ouzo.

© Giorgos Atsametakis

“The best mezes to accompany ouzo is lightheartedness,” said Ioannis Barbayannis, one of the first distillers on the island of Lesvos, referring to the small, tapas-like dishes normally served with the island’s signature drink. His point was that the off-white aperitif, with its sweet liveliness and aniseed-laden aroma, is not a drink to be sipped at a bar accompanied by loud music and nuts. It is most at home on a small table by the sea, to be enjoyed with choice seafood appetizers and, more importantly, good company.

The renowned food writer Christos Zouraris made a similar point in his book Deipnosofistis (Deipnosophist): “At ouzo-time the mood of the group is happy and light, but the diners neither raise their voices nor carry on at length. Their talk is laconic and concise. At this time they neither raise nor elaborate on issues at length, instead simply noting events and summarizing experiences. At ouzo-time the participants deliberately avoid weighty issues, knowing full well that they will face them in due time.”

“The best mezes to accompany ouzo is lightheartedness”

Enjoy a glass of chilled ouzo and taste the playful combinations of flavors through the small accompanying dishes

© George Drakopoulos

For Greeks, the act of drinking ouzo has elements of a ritual. This strong spirit is consumed as an aperitif – that is, it is thought to stimulate the salivary glands and digestive system, thus preparing one’s appetite for the main meal. That fact alone renders the consumption of ouzo a social activity. “To our first” is the common toast that groups will make each time their glasses are refilled so that they lose track of how many they’ve had. There is no keeping count; blissful self-imposed ignorance is preferred. “Relax, it’s only the first one.” The aim is not to stuff oneself, but to enjoy playful combinations of flavors through the small accompanying dishes: octopus, salted sardines, shrimp, shellfish, soft mizithra cheese and mint pies, beans, dips, pickles, etc.

Ouzo is colorless and serious drinkers (correctly) consume it neat. But most will add water in order to dilute the alcohol and sugars, an act which gives the drink its characteristic off-white, almost bluish cloudiness which derives from the aniseed. Traditionally ouzo is served in tall, slim glasses and it is properly served by pouring the ouzo in first, followed by cold water and then ice. This allows the spirit to cool gradually, leaving all of its aromas intact (some, of course, continue to regard the addition of any ice at all as a sacrilege).

“Ouzo is colorless and serious drinkers (correctly) consume it neat.”

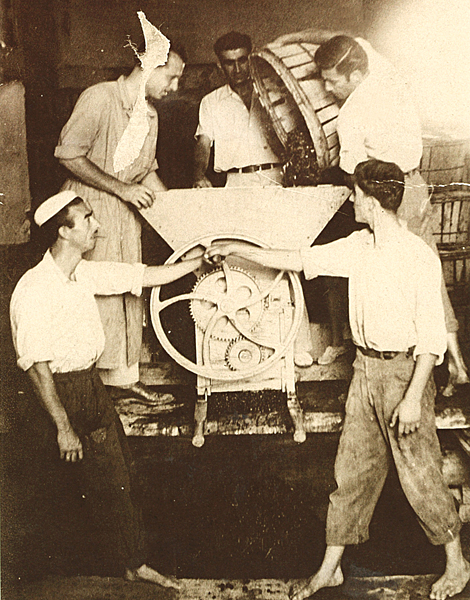

The 'spastiras' in use at the old Barbayiannis factory. The owner can be discerned in the middle.

© Ouzo Barbayianni: "Distillation of life."

'Drimoniasma' is the traditional process by which the seeds of the anise plant are separated from the stems.

© Ouzo Barbayianni: "Distillation of life."

In 1989, the European Union gave Greece the right to label ouzo as an exclusively Greek product. When and how the production of Greece’s trademark drink first began is not precisely known, but the oldest distilleries date back to the 19th century. “The refugees, our parents, who came from the Turkish coast in 1922, brought the secret with them. They distilled it. Ouzo making was the profession of the bourgeoisie, people drank then, they had faced many difficulties,” says Apostolos Linos, owner of Kefi distillery which opened in 1926. For his part, Stratis Andriotis, a worker for many years at the Matis distillery, which dates back to 1861, mentions that the island traditionally had extensive vineyards but that after the 1920s, when a phylloxera blight spread destruction across the island, these were replaced by potato and olive crops. Indeed today Lesvos has extensive olive plantations, while the remaining vineyards do not produce enough alcohol to meet the needs of the 17 distilleries that exist on the island. As such the majority of ouzo producers source the raw alcohol they need from Patras, Corinth and other Greek regions.

The distillers on Lesvos still stick to largely traditional methods of producing ouzo. Also unchanged are their recipes, each one a unique and closely guarded secret. In large copper stills (known as alembics) rectified (grape) alcohol is mixed with aniseed, water from the island’s springs and other aromatic herbs from Lesvos, and then heated. The resulting steam is cooled in a special tube, and the ice-cold condensate is collected, the raw form of ouzo. This process can take 12–15 hours and happens under careful scrutiny, with a slow distillation process improving the quality of the final product. The “head” and “tail” of the distillation process – that is, the first and last fractions to be produced – are discarded as they contain unwanted aromas. Only the “heart” of the distillation is kept.

“The distillers on Lesvos still stick to largely traditional methods of producing ouzo. Also unchanged are their recipes, each one a unique and closely guarded secret.”

Old copper alembic stills resting in the Barbayiannis museum

© Ouzo Barbayianni: "Distillation of life."

The distillation flows under controlled conditions.

© Dionysis Kouris

Barbayiannis ouzo has always been a 100% distillate.

© Dionysis Kouris

This remainder is then transferred to large vats where it is kept for 40 to 60 days. This is, in part, to ensure the ouzo reaches ambient temperature – for it to “rest,” as master ouzo producers say, and for all of the ingredients to bond with each other, producing a homogenous final product. The ouzo is then bottled. By law the alcohol content must be printed on the label, which can range from 37,5 to 48 percent, as well as the percentage of the alcohol in the final product that comes from the distillation process (at least 20% of the product’s alcoholic content must be ouzo distillate for a product to qualify as ouzo, according to EU regulations). There are of course ouzos that are made from “100% distillate” (as opposed to mixtures with cheaper, flavored alcohol), which are considered the best.

“What keeps you in this business?” I ask Apostolos Linos, who started working with his father, an award-winning distiller on Lesvos, when he was only thirteen. “Love, my dear, history…,” he says, close to welling up. “Until he died at the age of 87, my father was here every day. He oversaw everything. He worked from the morning, had a break at noon to have his ouzo, always with two hapselia [small, local, salted fish], and then he would carry on. I also have an ekatostari [100ml bottle] every day. You may come in here and find the smell very strong but we don’t notice it. This distillery has operated since 1926 and we are proud of it. I love doing this. I say it and I feel moved. And whenever I come here it’s like the first time I set up a distillation. I live it. I feel it. All night as I sleep I have in my mind how to make the next distillation better than the last. And I have been doing this since the age of 13 and I am now 60.”

The village of Plomari is particularly tied to the production of ouzo and features the museums of two of the most famous ouzo-producing families: the Barbayannis and Arvanitis families. At the Barbayannis Ouzo Musuem (1st km on the Plomari–Mytilini road, tel. (+30) 22520.327.41), which is also the better of the two museums, one can see exhibits from over 150 years of the family’s history in ouzo making. Meanwhile at the World of Ouzo (Plomari Isidoros Arvanitis Distillery, Kampos Plagias, Plomari, tel. (+30) 22520.314.50), which is operated by the Arvanitis family who produce ouzo under the Plomari brand, exhibits provide detailed insights into the ouzo-making process as well as the unique characteristics of the island’s environment and microclimates.

The name “ouzo” stuck almost by mistake. When exports first began during the 19th century, for the product to pass from Italy to France, and specifically to Marseilles, which was one of the first cities to import the Greek product, the customs office would write on the crates “Uso di Massalia.” which simply means “For Use in Marseilles.”

While the Turks, who, according to the Lesvos distillers, had learned to make the drink from Greeks in Asia Minor, kept the name “raki,” the Greeks sought to distinguish theirs by co-opting the customs term “uso.”

Three traditional products serve as both...