Disability in Ancient Greece: Myths, Facts, and Accessibility...

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

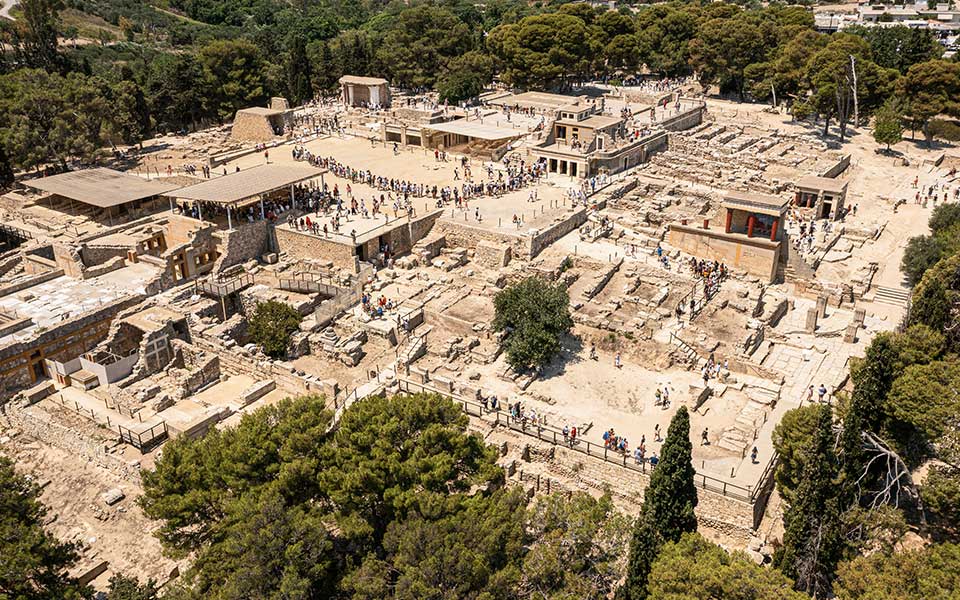

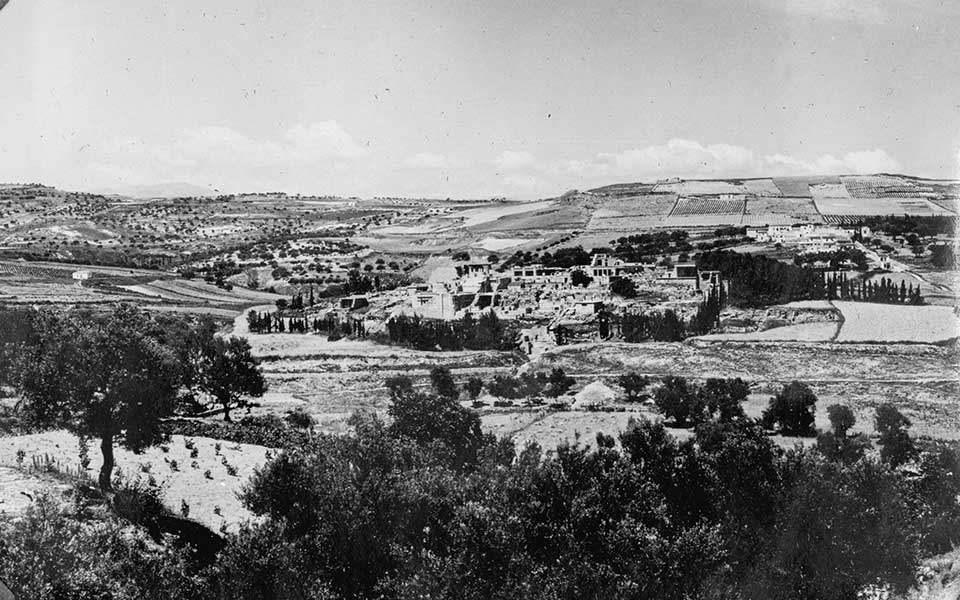

Panoramic view of the palace of Knossos.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

A small box containing carbonized emmer wheat seeds is the most precious exhibit at the Knossos Research Center Stratigraphical Museum, even though it does not sound as prestigious as the jars, black-figure amphorae, wall paintings, or figurines that are cataloged and stored in boxes. The seeds date back to the earliest stages of Knossos’ Neolithic settlement and were found in the 1960s in the palace’s central courtyard. Carbon dating determined their age to be 9,000 years old. These discoveries, along with cereal seeds and the bones of domesticated animals (sheep, goats, cattle, and pigs), constitute the earliest proof of a European society whose economy was based on agriculture and husbandry.

Situated a mere 300 meters from the Minoan palace, the British School at Athens’ Knossos Research Center serves as a hub for scholars, researchers, and students from around the globe who come to work in the Stratigraphical Museum and library. In fact, the latter is about to enter a new era. Over the next three years, it will undergo a major renovation, becoming “a state-of-the-art research center, in line with 21st-century standards, which will host Greek, British, and international programs focusing on the history of Knossos,” according to Mr. Kostis Christakis, curator of the center.

The 9,000-year-old charred seeds of emmer wheat discovered in the central courtyard of the palace in the 1960s are the most important discovery of the Stratigraphical Museum.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

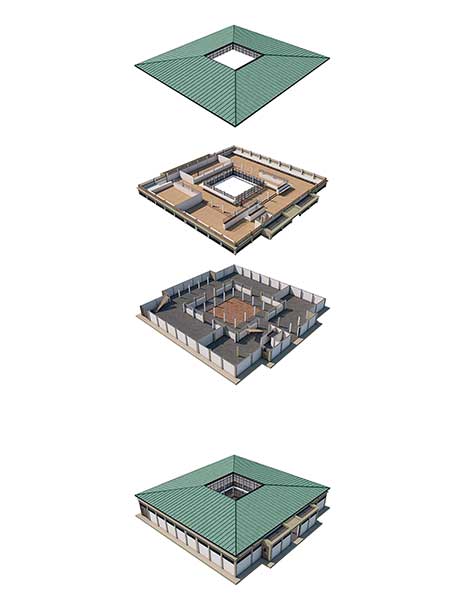

Photorealistic representation of the Stratigraphical Museum after renovation.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The renovation will be carried out in collaboration with the Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports and financed primarily by the Packard Humanities Institute, which will contribute approximately two million euros for the restoration of the 57-year-old museum. The construction of a 700-square-meter mezzanine floor, the strengthening of storage spaces, the creation of laboratories for ceramic analysis and bioarchaeological research, and improved conditions for the preservation and protection of artifacts, digitization, and online presentation of collections will provide the Stratigraphical Museum with the outward-looking impetus it needs to showcase Knossos’ archaeological wealth more effectively. The museum will continue to serve the academic community while also becoming more accessible to the public through lectures and cultural events. “Our goal is to educate the next generation of archaeologists while also making academic knowledge available to non-specialists. We aim to promote the dissemination of research in the local community. This is what we hope the British School will contribute. When the local community hosts and supports you, you have a duty to reciprocate,” says Mr. Christakis.

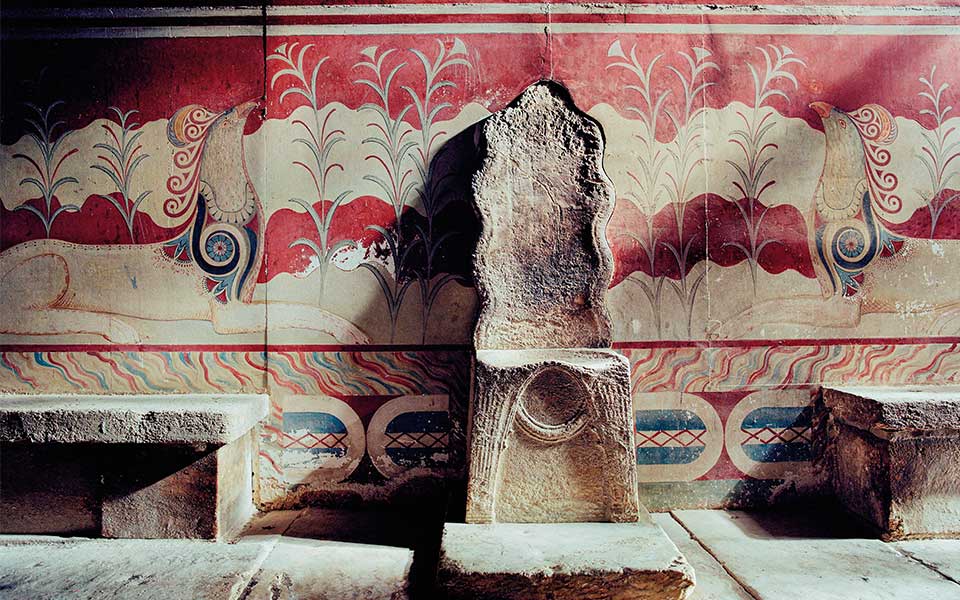

Complex of rooms at Knossos, which Arthur Evans named the "Throne Room." The central space, complete with the stone throne and benches, is visible.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

The local community has a long-standing connection with Knossos, as excavations at the site have defined the character of Iraklio since the late nineteenth century. It’s worth looking back in time to see how one of Greece’s most important archaeological sites was identified, uncovered, and researched; how this discovery shook the circles of European intellectuals and was used as a political pressure point before going down in history as Crete’s most important archaeological legacy.

To understand the timeline of the excavation of Knossos, we must first consider the political context of the time. The Cretan Revolution against the Ottomans began in 1866 but failed. The Ottomans massacred thousands of Christians in Iraklio in 1898, the same year the Cretan State was established. At this point, Crete found itself at a crossroads between self-determination, the Ottoman threat, and the ambitions of Great Powers. After the Balkan Wars came to an end in 1913, Crete was united with the rest of Greece, and World War I started. The excavations at Knossos, which tentatively started in 1875 and reached their zenith in the early 20th century, coincided with the redrawing of borders and Crete’s urgent desire to transition from being a province of an Eastern empire to becoming part of a European nation.

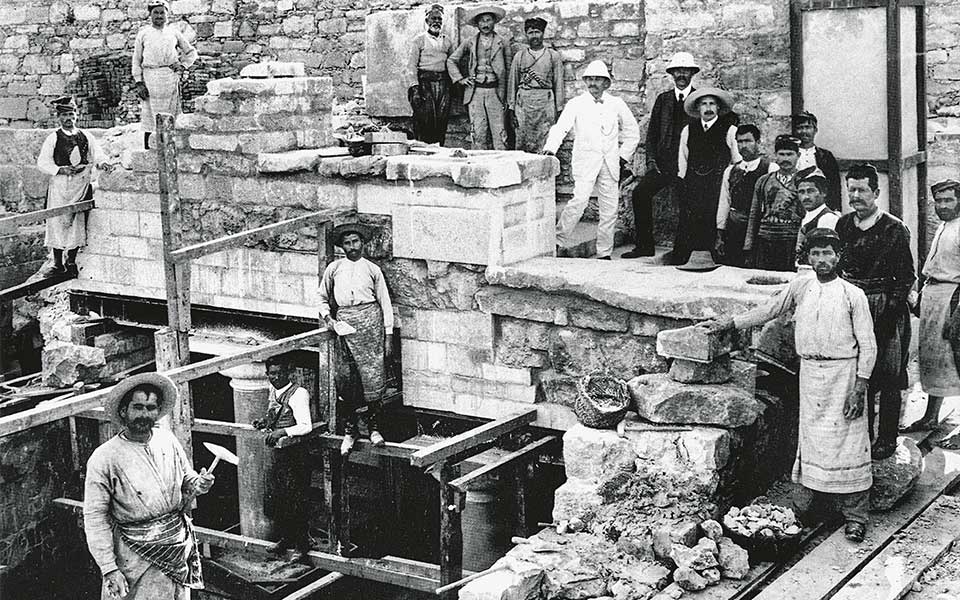

Evans and his team take a short break from restoring the Grand Staircase to pose for a photograph.

© Ashmolean Museum, Oxford

The location of Knossos was known as early as the late 15th century, when European travelers visited the hill of Kefala in hopes of viewing the legendary Minos Palace, only to be let down by the mere sight of the ruins. Knossos served as a quarry for ready-made building materials. Materials from Knossos were used in the construction of numerous buildings both during the Venetian era and in subsequent times. The first excavator of Knossos was the antiquarian Minos Kalokairinos, a member of one of the most prominent families of Iraklio, who made it his life’s work to discover the palace of Minos. Kalokairinos identified parts of the palace complex and unearthed various artifacts from the ruins, which he took to his home only for them to be destroyed on August 25, 1896, the day of the great massacre of the Christians by the Ottomans.

“Kalokairinos’ great contribution is not so much that he located the site of Knossos, as it was inevitable that someone would find it eventually. It is that, during the excavation period, he corresponded with the international scientific community to communicate his findings. He discovered a number of jars and offered them to the British Museum, the Italian and Spanish kingdoms, and so forth in the hopes that this would draw in Europeans with the resources and expertise to excavate Knossos at a time when the Cretans were struggling to rebuild their lives, rebel against Ottoman rule, and become part of European modernity. This is the greatest contribution of the pioneer of Cretan archaeology,” who shared the same name as the mythical king, as did other children of his generation who adopted ancient Greek names to strengthen the link between Ottoman-occupied Crete and ancient Greece.

The two figures who defined the excavations at Knossos: on the left, British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans; on the right, amateur archaeologist Minos Kalokairinos.

© Gainew Gallery / VISUALHELLAS.GR

The two figures who defined the excavations at Knossos: on the left, British archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans; on the right, amateur archaeologist Minos Kalokairinos.

© Hulton-Deutsch Collection / CORBIS / Getty Images / Ideal Image

Kalokairinos’s excavations were completed in a relatively short period of time, in the late 1870s, and marked the beginning of what became known as the “Battle of Knossos”. It was Arthur Evans who would eventually discover the historical thread on the hill of Kefala, although notable archaeologists like Schliemann and Stillman also made attempts. A British scholar, archaeologist and head of the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford, Arthur Evans (son of paper manufacturer and archaeologist-geologist, John Evans) visited Crete in 1894 in search of ancient inscriptions and signet rings. He traveled through numerous locations before meeting Kalokairinos, who even gave him a personal tour of Knossos. Evans’ British ancestry and considerable wealth allowed him to purchase a sizable piece of land at Kefala and become systematically involved in the excavation of Knossos. “Archaeologists Xanthoudidis and Hatzidakis of the Educational Society of Iraklio asked him to hold off until the political situation had stabilized. When this finally happened, Evans bought the remaining part of Kefala in 1899 and was able to finally start excavations at Knossos with the permission of the Cretan State,” Mr. Christakis notes.

Evans and his team traveled to Knossos. “Among his closest collaborators was Duncan Mackenzie, a Scottish archaeologist with extensive excavation experience [editor’s note: he excavated Phylakopi in Milos]. The science of archaeology was essentially born in the early 20th century, and geology had a significant influence on it.” Work began at Knossos in March of 1900, with Evans’ team approaching the excavation in the manner of a group of geologists. In archaeology, as in geology, there are overlapping layers. The process of stratigraphic excavation is like slicing a cake to reveal the different layers. This is what Evans, who published the first stratigraphic sequences, did in collaboration with Mackenzie, a key figure behind the scenes who was the keeper of the priceless Knossos diaries.

The Palace of Knossos as seen from the eastern bank of the Kairatos River, 1933.

© Βρετανική Σχολή Αθηνών

The discovery of the Throne Room in 1901 was a watershed moment in the Knossos saga. “The primary concern of Evans and his team was to house and protect the monument,” notes Elisavet Kavoulaki, Director of the Iraklio Ephorate of Antiquities’ Prehistoric and Classical Antiquities Department. “They discovered that the Throne Room had been severely damaged by rainfall, humidity, and temperature fluctuations between day and night. Evans’ associate, architect Theodore Fyfe, constructed a flat, waterproof roof using materials that would have been similar to those used by the Minoans. Ancient wooden columns were reconstructed from limestone and stucco for support. Brick pillars were also built to support the wooden beams.” Fyfe’s roof was replaced a few years later with one made of tiles, a material that, like everything else used before World War I, could easily be replaced.

The major shift in the excavation and restoration of Knossos occurred in 1920, when excavations resumed for the first time after a seven-year hiatus due to the war. “When Duncan Mackenzie went to Knossos, he encountered a disappointing situation.” The areas that had been sheltered were in better shape, but the rest had been destroyed. As a result, covering the sites was the only option,” Ms. Kavoulaki explains.

This marked the beginning of the so-called “New Era” of Knossos; Evans, along with his primary collaborator, architect Piet de Jong, started using reinforced concrete, a material which was very popular throughout Europe during that time. “In their effort to cover the Hall of the Double Axes or the Palace of the King, they used reinforced concrete for the first time and with great care. Today visitors are invited to admire an ancient monument that, after Evans’ restoration, is actually a composite structure made of both authentic elements and parts constructed from contemporary materials, creating a sense of the structure’s initial appearance prior to its destruction. The missing and unreconstructed sections have not been preserved. The deliberately interrupted concrete slab or the unfinished column standing on a limestone base suggest both the original image of the monument and what it looked like during the excavation. The palace of Knossos thus combines the appearance of a ruin with that of a well-preserved monument, in a wonderful way. It was a very modern approach to things,” explains Ms. Kavoulaki.

The Minoans used stone bull horns known as Horns of Consecration to decorate important buildings. Evans used reinforced concrete to restore parts.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

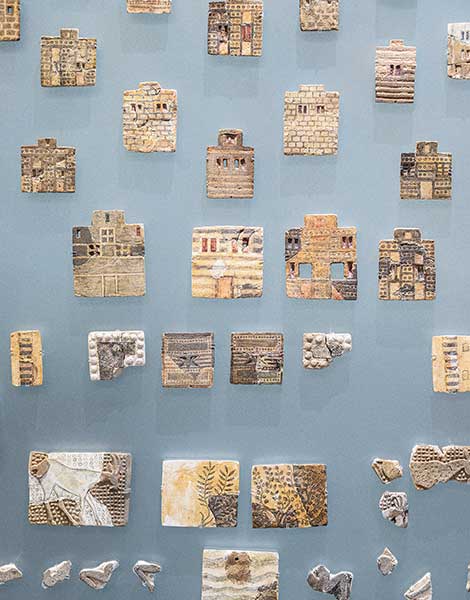

Set of faience plaques (1700-1600 BC) named "Town Mosaic" by Evans. They were used to decorate the inlay of a piece of wooden furniture.

© Konstantinos Tsakalidis

Evans and his team completed the excavations at Knossos in 1933, and he died eight years later. Some interventions were made in the decades since, but the archaeological site as it stands today is Evans’s work. “Evans established the principles of Minoan archaeology, influenced by Darwinian, Spencerian, and Taylorian philosophical ideas about the evolution of species, namely, that civilizations are organisms that are born, grow, and die. He laid the foundations and shaped the image of the prehistoric civilization of Crete, which he named ‘Minoan’,” notes Mr. Christakis.

Over time, the work of Evans and his collaborators has been evaluated from various perspectives. In addition to the excavation team’s strengths, such as their knowledge, experience, diligence, dedication, perseverance, and impressive results, one couldn’t help but notice their shortcomings. These included the interpretation of Knossos sites based on Homeric epic anachronisms, the arbitrary naming of rooms (e.g., the Queen’s Megaron), the presentation of incorrect information (such as the claim that the Minoans had an exceptionally advanced civilization with hot and cold running water), and the excessive use of reinforced concrete. Evans was a true visionary who boldly tackled the challenge of Knossos. If we approach his work with the same boldness, we can say that, in his attempt to provide visitors with an authentic experience of the ancient city, he crossed the line from archaeology to art. Knossos is the only archaeological site in Greece where the excavation reflects so much of the excavator’s personality.

The archaeological community’s current vision is to preserve the Minoan monuments, to maintain and continue Evans’ work, and to broaden its understanding of the ancient city’s physiognomy. Only about 2-3% of Knossos has been excavated, with most of the excavations focusing on the elite levels of Minoan society. “It’s like talking about 18th-century France and only referring to Louis XIV,” Mr. Christakis observes, confirming that the goal of contemporary archaeologists is to broaden their knowledge of everyday life at Knossos, which has already been the focus of much academic research.

Kostis Christakis, curator of the Knossos Research Center, at the Stratigraphical Museum.

They came from the East to colonize the deserted island of Crete, worshiped a female deity vividly depicted as a bare-breasted woman with snakes, prospered, and were eventually destroyed by the eruption of the volcano of Santorini. This is a widely held view that only partially captures the truth about who the Minoans were. According to current data, the seeds of Minoan civilization were planted during the Neolithic period, around 7000 BC, when farmers from southwestern Asia Minor migrated to Crete and mixed with the local population. This fusion of Eastern and native Cretan elements, along with the Minoans’ continuous capacity to absorb elements from peoples they interacted with, is precisely what makes Minoan civilization so remarkable.

Key dates in the development of Minoan civilization include the introduction of metal in 3100 BC and the Palatial periods (2000–1100 BC) leading up to the Neopalatial period (1700–1450 BC), when the Minoans strengthened their ties with the East. They imported valuable raw materials (gold, silver, copper, ivory, and glass) from Egypt, Syro-Palestine, and Afghanistan and exported agricultural products, cosmetics, textiles, leather goods, and, most importantly, aesthetics and ideas.

Knossos artists traveled abroad to decorate foreign palaces and introduce the beauty of Crete to the political elites of their day. The Minoans, who had a strong hierarchical structure in which wealth accumulated at the top of the pyramid, most likely followed a supreme ruler named “Minos” (similar to the Egyptian “Pharaoh”), although it’s possible that Minos originated from the Mycenaean mythology, which held that he was the son of Zeus, their own great god. However, it is believed that the man-eating Minotaur that prowled the Labyrinth and demanded a blood sacrifice was a fabrication of ancient Athenian propaganda. The Athenians sought to prove their superiority over a civilization that purportedly still engaged in human sacrifice by means of this myth.

The religion of the Minoans is an incomplete puzzle, owing to a lack of relevant written sources. Depictions of women in poses that denote leadership found on rings, seals, frescoes, or figurines (see Snake Goddesses) are insufficient to prove that the Minoans worshiped a Great Goddess, or that Minoan society was matriarchal. This misconception originates in the period of the “discovery” of Minoan civilization: when systematic excavations began in Knossos in the early 20th century, the science of social anthropology was dominated by James Fraser, who believed that all cultures worshipped a woman. Fraser, however, was raised in the British Empire, then headed by Queen Victoria. The presence of a woman at the helm of the world’s most powerful force for 63 years is thought to have influenced the scientific conclusions of Fraser and the archaeologists of the time. Regardless of the Minoans’ political system, supreme rulers, and deities, we know that their civilization collapsed in the middle of the second millennium BC, but not as a result of the eruption of the Santorini volcano. All Minoan palaces, except Knossos, are thought to have been destroyed in 1450 BC due to class conflicts and unrest. The mighty Knossos endured until 1300 BC, when its palace was abandoned for reasons unknown. During the first millennium, the Minoan city developed into a city-state that flourished and declined, and was only able to survive until the present day thanks to the settlements of Makrytihos and Bougada Metohi.

We would like to thank Mr. Kostis Christakis, curator of the Knossos Research Center of the British School at Athens, for providing information regarding the Minoan civilization.

Professor Debby Sneed explores disability in...

With fewer tourists, sunlit harbors, and...

Archaeology reveals powerful Iron Age women...

From Neolithic findings to haunting legends,...