Sitting at a taverna, I hear ice cubes tumbling into a glass at a nearby table, and a cicada getting quite comfortable in the reed fencing. There’s a smell of fish in the air. Dimitra is busy frying in the kitchen while “Ioanna,” the family’s fishing boat, gently bobs up and down on the crystalline water in front of me. Ioanna Ventouris, for whom the boat was named, is busy in the kitchen, too. Every day, in the family taverna they serve fasolakia (green beans) sourced from their garden, red mullet caught a few hours before, and meat from one of the three stockbreeders on the island.

Kalamitsi Taverna has just ten tables spread out on the sand, the best way to dine in summer. “We don’t want anything to change here – isn’t this why you all love us?” asks Dimitris Ventouris, who opened this small taverna some 20 years ago. His son, Stelios, has now taken it over, but he, too, has no plans to change the restaurant’s traditions.

© Nikos Boutsikos

© Nikos Boutsikos

Kimolos, like the food at this eatery, remains pure and authentic, simple and genuine. The island is impressively underdeveloped, with one largely dirt road that runs for approximately 12km; the rest of the island, a total of 37.43 square kilometers, is only accessible by foot or by sea. There’s only one ferry from Piraeus to Kimolos, and it moves rather slowly, a prelude to the relaxing pace that awaits you here. The number of hotel rooms is regulated, and there are only a dozen restaurants. Locals do not, as a rule, sell their land, and most have other occupations besides tourism. At the same time, change is coming, if slowly; the old fishermen’s houses and shops in Goupa and Karra, dug into the soft stone, are gradually being converted into luxurious rooms to let, and once humble tavernas are starting to offer gourmet menus.

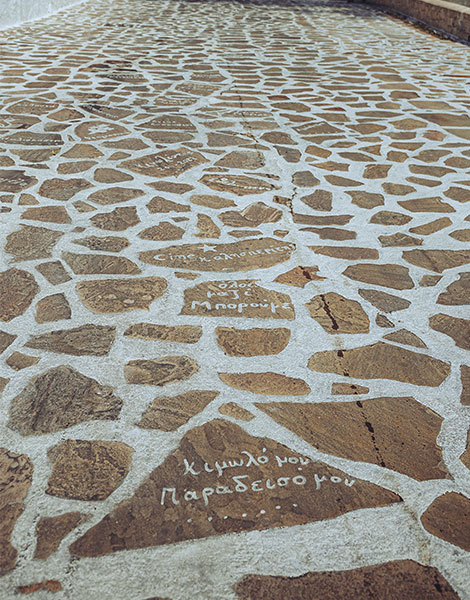

The local cultural group Kimolistes, which organizes beach cleanups and the whitewashing of stone paths, has set up lending libraries in boats and manages Cine Kalisperitis, the nomadic outdoor cinema that earned first prize at the ECTN Awards 2021 in the “Sustainable Cultural Tourism” category. There’s nothing like sitting on a beach in the midst of ruined castle and watching a movie under the stars.

© Nikos Boutsikos

© Nikos Boutsikos

These are the great things you’ll find on Kimolos, along with beautiful beaches such as Aliki, Bonatsa, and Kalamitsi, all with soft sand, tamarisk trees and the steady hum of cicadas. The most famous of these spots is Prassa Beach, where coarse sand formed from white rocks makes the waters phosphorescent. The large bay at Prasonisi is a popular mooring spot for yachts, and there’s a beach bar here, too, uncharacteristic of the island’s tranquil character; it plays loud music, often electronic. Dekas Beach, once a hangout for campers, is less developed. At Ellinika Beach, snorkelers can spot the ruins of ancient Kimolos on the seabed.

Monastiria and Soufi beaches are quieter places; you’ll need to walk to reach the latter. Mavrospilia Beach offers a relaxed beach bar where you can enjoy a lovely sunset framed by the peculiar rock formations found there. Kimolos has such rock features because, like its neighbor Milos, it underwent volcanic eruptions millions of years ago. The volcanic ash produced impressive stone shapes, different pigments in the soil, and great mineral wealth in the form of white silicate minerals whose chalky color gave the island’s name. Mining for these materials began in antiquity, and what was extracted was largely used as detergent. The export of figs also brought great prosperity in the 3rd century BC, and the island earned the right to mint its own currency. This period of economic boom lasted until a disastrous earthquake struck in the early Christian period. You can learn more about the history of the island at the small archaeological museum in Horio.

© Nikos Boutsikos

© Nikos Boutsikos

Throughout Kimolos, you’ll find traces of old mines and their conveyors, and there’s even an active mine in Pigado that still exports bentonite and pozzolan. The island’s special geology is evident everywhere: the “Elephant” rock in the village of Goupa, the “Rhinoceros” rock and carved tombs at Ellinika Beach, the rocks at Geronikola Bay, and the hot springs at Therma and Agioklima beaches.

The most impressive of these geological sites can be admired from the sea. Vangelis Vamvakaris’ boat “Delfini” can take you to see the caves and rock formations on the north side of the island. Take your mask and snorkel and swim over coral beds and through schools of multicolored fish. A visit to nearby Poliegos, an islet inhabited by a single farmer, will reward you with golden sandy beaches, turquoise waters, multicolored rock outcroppings and beautiful caves. You’ll find amazing blue waters here at the beaches of Pano and Kato Mersini, Panagia, and Avmoura.

Be sure to check out the abandoned lighthouse, the impressive caves at Fanara, and the three islets of Kalogeroi, always covered in flocks of seabirds; you might be lucky enough to spot some seals nearby as well. Whatever you see on or around Poliegos, however, Vamvakaris will be glad to share his knowledge and encourage you to respect and help preserve this unspoiled environment, which serves as a breeding ground for several species and has been incorporated in the Natura 2000 network as a Site of Community Importance for its rare endemic species of plants and animals, such as the venomous red Macrovipera schweizeri snake, the Podarcis milensis lizard, and the wild goats.

© Nikos Boutsikos

Walks and Trails

The most famous geological formation on Kimolos is called Skiadi; it’s a mushroom-shaped rock composed of 70 different kinds of rock. Pay a visit in the golden light of late afternoon after a beautiful 30-minute hike. In addition to the lovely view over the hills and sea, you will pass dry stone walls, olive groves (Kimolos also produces olive oil), and a traditional stone farmhouse with a threshing floor. The footpath for Skiadi is accessible from Horio, but you’ll have to ask locals where it begins. It’s the only one that is well signposted once you’ve found it. Still, it’s a good idea to download a map from the website kimolos.gr.

© Nikos Boutsikos

The island’s capital

In Horio – unlike on most Cycladic islands, the main village here isn’t called Hora – you’ll enjoy lovely walks and lively evenings. At the parking lot on the edge of town, you’ll find maps of the village; these routes are also signposted. This is an initiative by the group Anavasi to help visitors navigate the labyrinthine village, a large Cycladic settlement with whitewashed streets, small squares, and many 17th-century churches.

The village of Horio sprung up around an older fortified settlement, constructed circa AD 1200. Taking the paths from Pano or Kato Porta means you’re following age-old trails. Ruins along these routes feature escutcheons, coats of arms, and pilasters. Built using local ironstone, the fortified settlement was once square in shape, and the houses were constructed in two rows, the outer row functioning as a defensive wall. The oldest church in the village, the Church of Christ, built in 1592, is found within this once-walled area.

© Nikos Boutsikos

© Nikos Boutsikos

At some point within this old district, you’re certain to end up on the main pathway, Agora, where you’ll come across children at play, friendly cats, and a number of attractive bars; Brachera has a small roof patio; Agora and Laikon are on the same street. The atmospheric bar known as Stavento, right around the corner, has good music.

If you’d rather hear the sea while you sip, head down to Psathi, the island’s small port, which is quiet and picturesque. Lostromos, one of the oldest cafés on the island, is open all day and has a wonderful host: Cuervo, the port’s mascot Labrador, who will welcome you like an old friend every time he sees you.