Are you looking to avoid the crowds? Do you enjoy Greek history and exploring less populated spots in this age-old city of Athens? Perhaps you’d like a stroll through a peaceful, green archaeological park bisected by a small, ancient, tree-shaded riverbed still burbling with water. If so, put on your walking shoes and head for the Kerameikos – an archaeological site located only a short distance down Ermou Street from Monastiraki and the Thiseio metro station.

© Perikles Merakos

Into the countryside…

Today, the Kerameikos is often thought of as simply the cemetery of ancient Athens, thanks to the 5th- and 4th-century BC sculpted grave stones from the site now displayed in the National Archaeological Museum, or the iconic Geometric-era painted vase/grave marker known as the Dipylon Amphora (about 750 BC) – as tall as a person! – that depicts a funerary procession of hair-tearing women and men mourning a deceased woman of wealth lying on a bier. However, it was so much more than that. Its general tranquility nowadays belies the fact that the Kerameikos district was once a hive of activity where, on an ordinary day, a visitor might have heard not only the tinkling tune of the Eridanos River, but also the sounds of horses’ hooves and creaking cartwheels on stony roads, gravediggers scraping their shovels on stone, professional mourners wailing, potters singing to themselves as they worked over their wheels, city guards conversing, or a brothel-keeper calling out to passers-by as they entered or exited the gates. This was a place of transition, between the inner and outer worlds of the walled Classical and Hellenistic city of Athens, where, like today, one got the sense of leaving urban life behind and moving into a different, more countrified atmosphere.

Encompassing the northwest area of ancient Athens, Kerameis, the deme or municipality from which the Kerameikos (“Potters’ Quarter”) derived its name, once stretched from the Athenian Agora all the way to the olive groves of Plato’s Academy – a distance of about 1.5 km. Attracted by the rich clay of the Eridanos’ moist banks, craftsmen were already setting up pottery workshops in the Kerameikos by at least the 8th century BC, but people wishing to bury their dead had exploited the marshy area as early as the Bronze Age. After about 1200 BC, more frequent, organized use of the cemetery was marked by the appearance of grave monuments that included impressive ceramic vessels and carved “kouros” statues, while during the Archaic era (6th century BC) distinctive mounds containing shaft graves for cremation burials and channels on their upper surfaces for grave goods were erected for Athenian noble families and dignitaries.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

An intriguing historical vista

A walk through the Kerameikos archaeological site best begins with an approach from Ermou Street. Looking down, you’ll have a panoramic view of the entire park, with the Sacred Gate below on the left and the Dipylon Gate on the right. Between them lies the internally colonnaded Pompeion building, while in the distance the large Church of Aghia Triada dominates the central background, with the Street of the Tombs and the Sacred Way on its left side and the Dromos, the main street from the Dipylon Gate, passing by on its right. This is a clearly defined archaeological site, cut deeply into the earth and bordered by tall, stone-reinforced embankments, paved streets, and contemporary offices or residential structures that have sprouted up around it since Greek and German archaeologists began excavating (in 1870 and 1913, respectively) to create this “window” into the past.

Once an open area with natural vegetation, a narrow riverbed, low burial mounds and elegant grave markers, the Kerameikos was divided in 478 BC, after the Persian Wars, by the building of the Themistoclean Wall and other city defenses. The district now took on a military character with strong gates, an outer wall (Proteichisma) and a protective moat. Outside, the cemetery grew larger and more ornate, until ostentatious grave monuments were banned in the late 4th century BC. Inside the gates, houses, workshops and public buildings were constructed. The Kerameikos became a bustling crossroads where one might rub shoulders with Athenians and foreigners from every walk of life: household slaves, foot soldiers, mounted knights, city officials, merchants hawking their wares, and the religious faithful heading out to worship at extra-mural shrines.

© Perikles Merakos

Exploring the ruins

On entering the archaeological site, visitors today can choose to go directly into the excellent albeit small Kerameikos Museum to the left or save that pleasure for later and head down into the excavated area. A fine view over the ruins can be had from the little hill at the start of the descent, where you’re also provided a detailed site plan for getting your bearings. Setting off downhill and following a counterclockwise route around the excavation, one initially encounters a high stretch of preserved city wall. From its lowest original Themistoclean courses, this wall rises in multiple phases to reflect the long tumultuous history of Athens. Demolished by the Spartan Lysander in 404 BC at the end of the Peloponnesian War, it was later repaired by Konon (394/3 BC) and further augmented and repaired up to the reign of Justinian (6th century AD).

Today, you can step through a narrow breach in the city wall and view just inside the remains of House Z, whose proximity to the fortifications meant that it, too, endured various assaults. Once a large private residence built shortly before 430 BC and featuring fifteen rooms arranged around two distinct courtyards – one for men, the other for women – the house was destroyed in about 425 BC and soon rebuilt, before being damaged again along with the adjacent city wall in 404 BC. Afterwards, it remained abandoned until about 350 BC, when it was once again rebuilt. Now, however, House Z no longer resembled a traditional family home, instead containing a single courtyard and many small rooms. A new well, three cisterns and dozens of loom weights indicate textile production, but the additional discovery of hundreds of cups and other tableware, knuckle bones, an ivory flute, and personal objects – including bronze figurines and medallions depicting Aphrodite, goddess of erotic love – suggest that House Z had become an establishment that offered drinking, dining, gambling, musical performances and female companionship. Each woman had her own room in which she apparently passed her time weaving when not occupied with entertaining. In Roman times, bronze and pottery workshops were installed among the structure’s ruins.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

The pilgrims gathering

Stepping back through the city wall, you turn right to cross the Sacred Way and the Eridanos riverbed. This is the area of the Sacred Gate, where, in early summer, ancient Athenians participating in the annual Skira festival assembled before making a procession to Skiron in the Attic countryside. In the autumn, at the start of the Greater Eleusinian Mysteries, a larger procession would also leave from here for the sanctuary of Demeter at Eleusis.

Beyond the Eridanos, the large Pompeion with its internal colonnaded courtyard served as a storage place for the ceremonial trireme and sacred objects used in the Panathenaic procession during the Panathenaic Festival. Equipped with four pebble-floored rooms containing 66 dining couches, it also functioned as a dining hall for the Athenian archons and their official guests. Later, it was overbuilt by workshops and a storehouse, possibly a granary. The building’s well-worn threshold attests to the many wagon wheels and thousands of Athenian feet that passed over it through the centuries.

The adjacent Dipylon Gate similarly enjoyed a periodic religious function, as every four years Athenian revelers met here to begin the Panathenaic procession from the Kerameikos to the Acropolis. The gate’s deep external courtyard, fortified with a second, outer gateway in Hellenistic times, not only provided greater security, but also a place for the public to gather in peace time. During the Panathenaic Festival, roasted meat from sacrifices was distributed to the people, who – based on excavated piles of animal bones – appear to have used the Dipylon courtyard as a feasting area. A fountain house stood just inside the gate, where Athenian women and servants could refill their water jars.

© Perikles Merakos

Spartans in Athens

Moving along the Dromos and away from the Dipylon Gate, you’ll be approaching the Demosion Sema, the Athenian state cemetery. Great tombs erected along this road marked the final resting places of important local figures and allies buried at state expense. Although Perikles’ tomb still awaits discovery somewhere beyond the excavation area, one of the most intriguing monuments visible today is the grave of Spartan officers who perished while giving assistance to the Athenian oligarchs in 403 BC during an unsuccessful fight in Piraeus against pro-democracy forces. The 11-meter-long enclosure held thirteen battle-scarred skeletons and was capped with a right-to-left inscription identifying them as “Lakedaimonioi.” The first two letters are still visible.

The cemetery

Returning westward toward the museum, you’ll traverse a grassy, park-like area and re-cross the Eridanos at a place that was once the site of an ancient bridge. This is one of the most charming spots in the Kerameikos today, with shady, broad-leafed trees overhead, and the age-old river passing beneath one’s feet. In the spring, the water teems with tadpoles and tiny frogs. On the near bank is a burial mound that the 2nd century AD traveler Pausanias also saw: “As you go to Eleusis from Athens along…the Sacred Way you see the tomb of Anthemocritus [about 431 BC]. The Megarians committed against him a most wicked deed, for when he had come as a herald to forbid them to encroach upon the land in future they put him to death.”

Ahead stand two distinctive steles at the foot of the little hill from which you started your tour. These mark the graves of two envoys from Corfu who died while visiting Athens on a diplomatic mission in 433 BC during the turbulent lead-up to the Peloponnesian War. The Sacred Way forks here, with the main route continuing toward Eleusis, and the Street of the Tombs opening to the left. The fork itself is occupied by the sacred precinct of the Tritopatreion, a small walled enclosure now shaded with olive trees that may have been associated with ancestor worship.

© Perikles Merakos

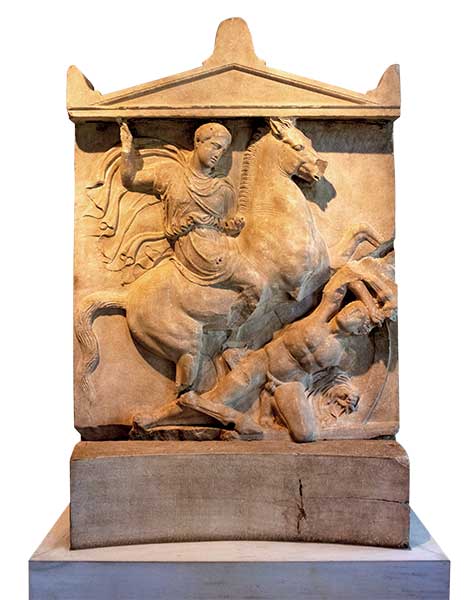

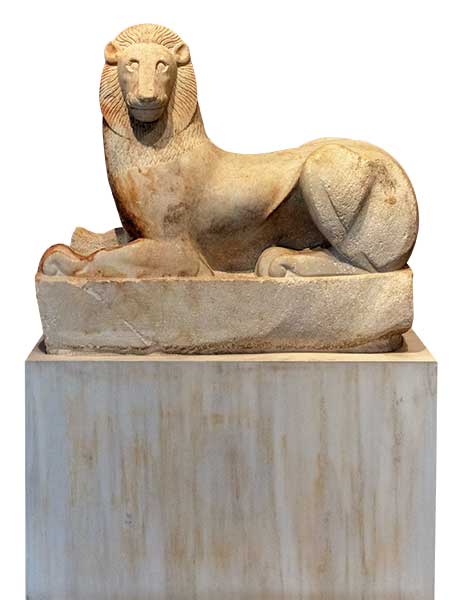

Lining the Street of the Tombs is a diverse array of impressive funerary monuments, including sculpted steles, over-sized loutrophoros vases and marble statues, some framed within small temple-like pavilions (naiskoi). Inscriptions have revealed the identities and origins of many of the deceased, mostly dating from the 4th century BC. On the right is the family plot of Koroibos of Melite; on the left are tombs belonging to Lysimachides, Dionysios of Kollytos, the brothers Agathon and Sosikrates from Herakleia on the Black Sea, and the family of Lysanias of Thorikos. Particularly striking is the pawing bull overlooking the Dionysios of Kollytos precinct (a reproduction), and the carved relief commemorating the horseman Dexileos, a relative of Lysanias, who died in battle against the Corinthians in 394/3 BC. Beside the path that will take you back up to the museum, another naiskos contains the sculpted images of two sisters, Demetria and Pamphile.

The museum

The Kerameikos experience isn’t complete without a visit to the site’s museum. Highlights include a fine Archaic-era kouros, original grave markers (including the massive, rippling-muscled 4th-century BC Bull of Dionysios of Kollytos), a collection of ceramic vessels and other funerary gifts, and household objects and personal items belonging to the residents of House Z.