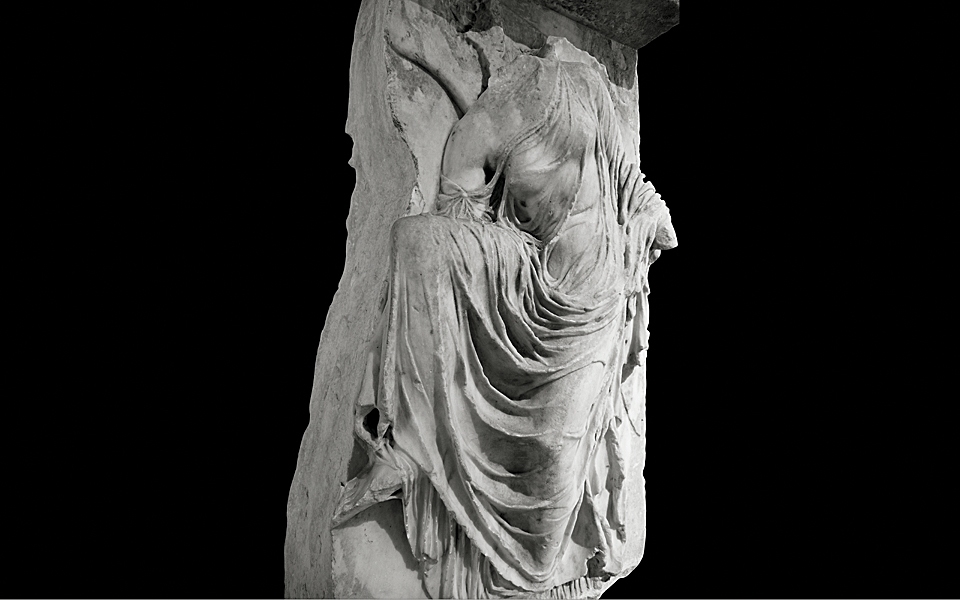

At last, more than a century after their discovery, eight of the Acropolis Museum’s most significant statues tell their story!

CARYATID, AN ELEGANT LADY OF ATHENS

Is there a religious ceremony about to take place?

My sister Caryatids and I are thought to be libation-bearers or attendants for Athens’ mythical king Cecrops. That’s probably why we adorn the Erechtheion’s South Porch – his tomb was located just below. We used to carry phialai (shallow libation bowls) in our hands; the tips of our knees pressing against our gowns indicate that we’re moving, perhaps rhythmically in a procession.

You’re also columns; is that unusual?

No, caryatids had already appeared in the Siphnian Treasury at Delphi about 530-525 BC. We were installed on the Acropolis a century later. The Erechtheion may have been started as part of Pericles’ great building program on the Sacred Rock… or at least by 421 BC. It was mostly complete by 406 BC, but – as you can see, if you examine the molding just below our feet – some decorative details were left unfinished. Those final years of the Peloponnesian War were difficult.

Mnesikles, the architect of the Propylaia, may have designed the Erechtheion, but who was your particular sculptor?

That’s still a mystery. Some say we came from the workshop of Alkamenes, a student and collaborator of the great Pheidias. We are enchanting, with our thick braided hair, clinging garments and unique, crown-like capitals resting on our heads. The vertical folds of our peploi recall the flutes of an actual column. We do carry a lot of weight on our heads.

Where does your name come from?

One local myth claimed we represent girls from Karyai, in the Peloponnesian region of Laconia. Vitruvius, the Roman architect, wrote that we are Carian women from Asia Minor, who sided with the Persians and now bear the weight of our guilt on our heads… But these are apocryphal tales. We are Korai, elegant ladies of Athens!

But one of you is missing. Where is she?

You are speaking of our sister, who is now in London. The people of Athens used to say they could hear us mourning for her at night, after she was taken by Lord Elgin.

“Our sculptor…? That’s still a mystery. Some say we came from the workshop of Alkamenes, a student and collaborator of the great Pheidias.”

SEATED SCRIBE, THE POWER OF THE WORD

Who are you… there on your stool?

I am an official Athenian scribe. I had quite an important job. Athens was a busy place in the 6th, 5th and 4th centuries BC! What with that ambitious tyrant Peisistratus, the pugnacious Persians, the First Athenian League, the Peloponnesian War and the Second Athenian League, there were always architects, builders, treasurers and other officials rushing about; generals and diplomats coming and going; politicians bustling between the Boule (Council) and the Ekklesia (People’s Assembly); and – for us scribes – plenty of state decisions, pronouncements and honorary decrees to be recorded…

How were Athenians kept informed of this official business?

Once decisions had been proposed by the Boule and approved by the Ekklesia, we transcribed them onto a papyrus roll, or a wax-lined wooden tablet, using a sharp bronze or bone stylus. Then, they were inscribed on stone steles, erected in prominent public spaces – especially the Agora (central square) and the Acropolis.

So, these “notice boards” were a common sight on the Sacred Rock?

Indeed; if you look just beside the visitors’ path as you ascend from the Propylaia, you’ll see slots in the bedrock that once held steles. People could read these documents as they passed.

What kinds of things did you record?

I’m an older scribe (ca. 510-500 BC), so my duties included documenting the leaders’ rulings and keeping accounts of public constructions, or the dedicatory treasure of Athena and the other gods. Later scribes also registered democratic actions by the Demos (citizens), public supervisors’ annual reports, foreign alliances, and who was to be given honors, such as free meals at the Prytaneion (Tholos/Executive Council’s Mess), front-row theater seats, the title of Ambassador, or even Athenian citizenship!

“My duties included documenting the leaders’ rulings and keeping accounts of public constructions, or the dedicatory treasure of Athena…”

PAPPOSILENOS, LOOKS CAN BE DECEIVING…

Greece Is: Are you the mythical Silenus, the wise teacher and companion of the wine god Dionysus?

Yes, but sometimes, when I look older, they like to call me Papposilenos.

We hear you’re fond of drunken revelries and often get carried home on a donkey. Is that appropriate for a figure of your stature?

Well, I am a satyr – we love drinking, dancing, making music… and we’re known for our cheeky, lewd behavior. Plus, I’m the leader of Dionysus’ entourage and I have to set an example for the younger satyrs. We’re an unruly bunch, especially the maenads – those high-spirited women who dance around in wine-induced ecstasy, usually working themselves into a violent frenzy!

Tutor, sidekick, chief satyr…what else can you tell us?

Well, in this particular manifestation as a statue (along with little Dionysus here on my shoulders, holding a theatrical mask), I used to adorn the Theater of Dionysus. But I also became a much-beloved character in those bawdy, tragicomical “satyr” plays.

You satyrs were originally forest men, weren’t you, and typically sport the ears, legs and tail of a horse. What’s with your present look?

Nowadays, I do have an uncanny resemblance to the philosopher Socrates; but he was a familiar, colorful figure around here, well known to Aeschylus, Sophocles, Euripides and the other playwrights who presented satyr plays on the Acropolis slopes.

Ah, you’re from 5th-century BC, Periclean Athens?

No, I’m not that old! My era is the 2nd century BC.

So, you’re actually a Roman copy, posing as a Classical Greek original?

Something like that. Don’t forget, in ancient Greek mythology and art looks can be deceiving!

“We’re an unruly bunch, especially the maenads – those high-spirited women who dance around in wine-induced ecstasy, usually working themselves into a violent frenzy!”

THE RIDER, ON PARADE IN ANCIENT ATHENS

Those horses are a little frisky.

They want the parade to begin! We’re getting them into formation for the dokimasia – the annual inspection of the Athenian cavalry. One of our commanders (hipparchoi) is just ahead, also trying to soothe his mount. He was likely carved by Pheidias himself, but most of us Parthenon figures were created (430s BC) by lesser sculptors of the master’s workshop.

You’re members of the cavalry? Aren’t there new interpretations of the Parthenon frieze these days?

The traditional view is that we’re all participants in a Greater Panathenaic procession in honor of Athena – during which a new peplos (robe) was presented to the goddess for her cult statue in the Erechtheion. Supposedly, the central scene over the Parthenon’s east entrance depicts the new garment’s presentation. In recent years, however, a fresh interpretation has been offered, in which the east frieze’s central scene is said instead to concern human sacrifice, involving the mythical Athenian king Erechtheus, his wife Praxithea and their three virgin daughters. It’s based on a familiar Athenian myth.

Where does that leave you?

We’re still cavalrymen. But now we’re participants in a sacrificial procession, held in honor of Erechtheus’ slain daughters. We riders accordingly belong to the king’s army, which, the myth says, defeated the invading forces of King Eumolpus of neighboring Eleusis. Athenian independence was thus divinely ensured, thanks to the sacrifice of Erechtheus’ offspring.

Which interpretation is correct?

The specialists are still talking… But the new view fits the other decorative themes portrayed on the Parthenon and Acropolis– military victory; order over chaos; patriotism and self-sacrifice, all in the name of Athenian supremacy and freedom. In Pericles’ day, these were key issues, fueled by Persian invasions, imperial expansion and all-for-one, one-for-all democratic reforms.

“Athenian independence was divinely ensured, thanks to the sacrifice of Erechtheus’ offspring.”

THE PEPLOS KORE, A COLORFUL LADY SMILES

… And you are the Peplos Kore, a work of that great Athenian sculptor whose name we do not know but refer to as the “Rampin Master?”

Yes; we korai first appeared on the Acropolis in the early 6th c BC. We’re all unique! I myself was sculpted around 530 BC. You can see that I’m a more recent figure – from my relaxed Archaic Smile, less stylized “Almond Eyes” and more naturalistic body.

You’re wearing a traditional Doric peplos (heavy woolen robe). Why is that?

Well, firstly, we Acropolis ladies are more modest than those nude kouros boys! We prefer to appear fully dressed, in our finest clothes. My own style is conservative… they say I’m a goddess – perhaps Artemis – though, I seem to have lost my bow and arrows. Other korai hold small offerings: a pear, a flower, a dove…

You korai are not all goddesses?

No, most of us are likely priestesses, temple attendants, or young women typically seen at public celebrations or ceremonies. The more progressive ladies among us tend to wear lighter, sheerer fashions, like those of Ionia (western Asia Minor) and the Aegean islands. That is, a linen chiton (tunic) beneath a himation (mantle).

We understand from the museum’s conservators that you were all once much more colorful.

Alas, our luxurious fabrics have indeed faded! Originally, our clothes, hair and faces gleamed with rich shades of blue, green, yellow and red. We looked very lifelike! My peplos was adorned with animal images and lovely palmettes, rosettes and running waves. We also wore painted or attached jewelry. I had a bronze wreath around my hair. Those metal fittings still visible on some korai’s heads weren’t so fashionable, but they kept pesky birds from landing and spoiling our appearance!

“They say I’m a goddess… but most of us Korai are likely priestesses, temple attendants, or young Athenian women typically seen at public celebrations or ceremonies…”

THE CALF-BEARER, A DEDICANT COMES TO WORSHIP

You must be The Calf-Bearer…? One of the eldest members of the statue community here in the Acropolis Museum?

Yes, I was one of the first statues produced when the Attic sculpture workshops got started in the early 7th century BC. My creator is still unknown, but the experts think I was carved about 570 BC.

How do they know you’re such an early sculpture?

For one thing, I’m made of white marble from Mount Hymettus, just outside Athens. In later years, Athenian sculptors largely switched to using finer-quality marble from the island of Paros. But I don’t feel old-fashioned; I’m an original… an icon! I’m in all the guidebooks and school texts!

You sound a little… supercilious.

Who are you exactly?

From my inscribed base, you’ll see I’m a dedication offered by Rhombos, son of Palos, who was probably a top Athenian aristocrat – a member of the 500-Measure social class, with the necessary means to make expensive gifts, such as me. Some say I’m Rhombos himself, bringing a calf to Athena as a sacrificial offering.

How else can we identify you as an early Archaic sculpture?

Well, look at my features – the distinctive “Archaic Smile,” almond-shaped eyes and stylized hair and anatomy. And check out these impressive “abs,” just above my button-like navel. I used to go to the gymnasium every day!

If you’re so old, how come you’re still in such great shape?

It was those rascally Persians. When they ransacked the Acropolis in 480 BC, they knocked me down, along with some of my other colleagues here in this gallery. Later, the Athenians buried us, when they were tidying up. So, here we are!

“I don’t feel old-fashioned; I’m an original… an icon! I’m in all the guidebooks and school texts!”

PENSIVE ATHENA, INSIDE THE MIND OF A GODDESS

If we may intrude on your quiet reflection, aren’t you Athena, the divine patroness of ancient Athens?

I initially had to compete for that role against the sea god Poseidon, but I prevailed… aided by a persuasive gift: the olive tree. That pivotal contest was commemorated in a sculptural scene in the Parthenon’s west pediment. My birth is featured in the opposite east pediment.

Would visitors have seen many tributes to you on the Acropolis?

This prominent hill was the seat of my cult – the foremost religious sanctuary in a city named after me. The Athenians were always finding new ways to express their respect, and to remind other city-states what a powerful goddess I am!

…You often appeared on steles such as this one?

My image regularly accompanied official steles. This relief (ca. 460 BC) may have been a boundary marker; or part of a treasury archive or solemn list of war dead. With my expression and heavy drapery folds, I represent the Severe Style, prior to the more idealized, fluid, lightly clad figures of the ensuing High Classical era.

Where might we have seen larger images of you?

The most visible was the colossal Bronze Athena, between the Erechtheion and the Propylaia. I was Athena Promachos, dressed in armor, holding a spear. This statue towered impressively over visitors as they emerged onto the Acropolis. It was so tall (at least 9m.) that sailors reputedly could see the tops of my helmet and spear as they approached from Sounion! With the sun flashing off my polished bronze, it must have been a glorious sight! Of course, the pièce de résistance was my gold and ivory cult statue, 10 meters tall, inside the cella of the Parthenon, created by the sculptor Pheidias!

“My image regularly accompanied official steles. This relief may have been a boundary marker; or part of a treasury archive or solemn list of war dead”

KRITIOS BOY, A COMPOSED ATHENIAN TEENAGER

You’re a handsome fellow. You look quite distinct from the earlier statues around here.

I’m what the art historians call a transitional figure. I represent an Athenian youth (ephebos), in the era after the Persian invasion of 480 BC. I was also preserved by the city’s clean-up/burial operation that followed the wartime destruction of the Acropolis. You’ll notice I have a very naturalistic appearance. No more stylized Archaic facial features. Instead, I’m portrayed as physically relaxed, mentally composed; still standing erect, but with my body weight predominantly on my left leg.

Is there still uncertainty concerning who carved you?

Yes, but whoever he was he has masterfully demonstrated an artistic canon later embraced by famous sculptors including Polykleitos, Praxiteles and Lysippos. Through me, he shows that although the body has many different parts, it can be unified symmetrically, by applying a system of ideal mathematical proportions and balance. You could say that I’m the first “digital” statue!

Your hips are narrower, with one side slightly higher than the other…

That’s the “contrapposto” effect, where my back is beginning to curve like an “S”… one hip down and the opposite shoulder up. I’m named after my creator Kritios, the same sculptor who depicted those tyrant-slayers Harmodius and Aristogeiton.

Your humor is a little surprising, given that you appear so serious.

My austere expression is characteristic. I’m perhaps the best known example of the “Severe Style,” a forerunner to the artistic sensibilities of Classical Athens’ Golden Age. My contribution to Greek art has been partly described as a newfound attitude of calm, post-war confidence; a harbinger of the Athenians’ blossoming ideological and visual emphasis on individualism, within their increasingly democratic society.

“I’m a forerunner to the artistic sensibilities of Classical Athens… My contribution to Greek art has been partly described as a newfound attitude of calm, post-war confidence…”

NIKE, EVEN GODDESSES REMOVE THEIR SANDALS

May we ask, where you are going?

Into a temple; but first I’m removing my sandals as a sign of respect. I represent victory, a familiar theme on the Acropolis, heralded by Pericles’ artists through their various decorative programs – as visual reminders of Athenian military might and success. The recurring association between Athena, patroness of Athens, and Nike, goddess of victory, was symbolic and propagandistic…

Where were Athena and Nike seen together?

In the Parthenon, a Nike nearly 2 meters high stood in the open, upturned hand of Pheidias’ statue of Athena Parthenos – dwarfed by the enormous figure, which (with its base) was more than five times taller! Other Nike figures appeared in the temple’s pediments, on its metopes and even on its roof, adorning the building’s four corners. Affluent worshipers would have dedicated marble, bronze or gold Nike figures to Athena as votive offerings.

Where were you?

The Sandalizomene relief was one of the marble slabs that formed a balustrade around the Athena Nike temple, built in the 430s and 420s BC. The balustrade itself was carved by at least six sculptors during the last decade or so of the Classical 5th century BC. There were about 50 Nikai depicted, moving gracefully, clad in near-transparent drapery. We are offering sacrifices to Athena and erecting trophies before and after battles.

Did Nikai appear on the temple itself?

Ten gilded bronze Nikai adorned the roof. The temple’s overall decorative theme was the victory of Greeks, specifically Athenians, in battles against Persians or other Greeks. Pedimental sculptures portrayed the Gigantomachy and Amazonomachy; the frieze illustrated Marathon and other historical or mythical battles. This little sanctuary may itself have been a votive offering by the Athenians, in the last years of the Peloponnesian War.

“The balustrade was carved by at least six sculptors… There were about 50 Nikai…moving gracefully, clad in near-transparent drapery…offering sacrifices to Athena and erecting trophies…”

THE ACROPOLIS MUSEUM

At the Acropolis Museum, the small details hold the key…from the soaring modern architectural features of the building itself and the ruins of an ancient, once-crowded neighborhood visible outside, to the scenes of women’s rituals and ancient everyday life found on Classical vases inside in the Acropolis Slopes Gallery. One also has to look beyond polished marble surfaces and stunning sculptural forms, however, remembering what is now missing, before one can fully appreciate the soul of ancient Greece.

Traces of once-bright paint still cling to Archaic Kore (maiden) statues; striding Caryatid ladies and graceful Nike goddesses attend to their sacred rituals; intricately carved original panels from the Parthenon’s metopes and frieze stand ready for inspection beside casts of their brethren now in foreign museums; while the view to the Acropolis and surrounding city, framed within the top-floor gallery’s all-glass walls, provides an inspiring bonus display to the museum’s already superb exhibits. Take a moment also to appreciate the friendly staff, the well-stocked book/souvenir shops and the excellent roof-top restaurant and café, offering delicious, freshly innovative fare.