The Authentic Flavors of Greece: Discovering Traditional Greek...

A journey through Greece’s living heritage,...

Freshly baked mussels, one of the specialties of Halkidiki

© Stella Spanou

The first smells to become imprinted on our memory are those we recall throughout our lives, it is said. Every time I return to Halkidiki, the smell of its foods and its natural scents bring back a flood of childhood recollections.

My family has a profound connection to food – and I don’t just mean in its enjoyment. My grandmother was an amazing cook who had worked in a Jewish household in Thessaloniki in the 1930s. At our house, her first task in the morning was to get the food simmering on the wood stove. Her specialty was a beef-and-potato stew in tomato sauce scented with allspice and cloves. It tasted of pure love. She’d first simmer the meat gently in water and spoon off the scum. Then she’d add the onions – never sautéed – and the ingredients for that sauce of her that was lighter than air. She’d chop the potatoes into large chunks and give them a quick fry, just until they started turning golden, so they’d hold together in the hot sauce. She’d always let me help with the stirring and it was at some point there, among her pots and pans, that those aromas first settled inside me.

Once the meal was cleared away, she’d get together with her friends for hours of knitting and idle chitchat that tended to focus on food (what was in season, new recipes, some culinary secrets), a custom that still holds in most villages. She taught me a lot. I’d set out for Mt Holomontas to gather mushrooms and would bring them back home so she could sort the edible from the inedible ones. (Today, truffles and many other species of wild mushroom are still collected on that beautiful mountain of central and eastern Halkidiki.) We’d gather snails, wild greens and chicory – my favorite still, served hot with lots of lemon.

“Every time I return to Halkidiki, the smell of its foods and its natural scents bring back a flood of childhood recollections.”

Mending nets at the boatyard.

© Perikles Merakos

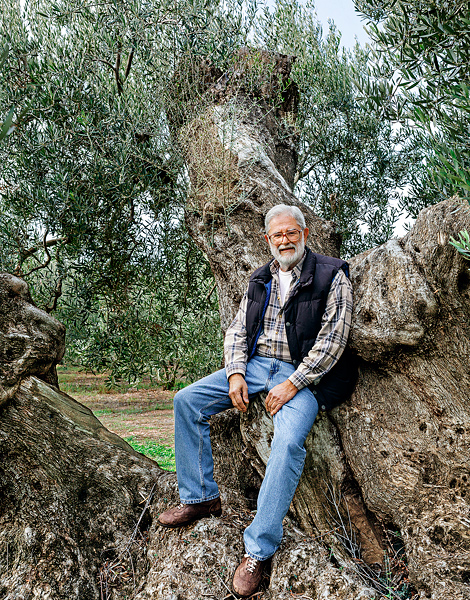

Dimitris Portolos, a pioneer of Halkidiki’s early-harvest olive oil.

The freshest catch of the day.

© Stella Spanou

“Our backyard was always full of wooden crates of salted mackerel, sardines and bonito.”

My grandfather was a fisherman who’d bring home whatever he hadn’t sold at the Nea Moudiana fish market, located on Halkidiki’s first finger, Kassandra. He’d cook the bigger fish as the monks do: in a stew with lots of vegetables, onions and lemon juice. He’d fry the smaller ones and add a dash of vinegar right at the end – it was his secret for bringing out their flavor. The rest would be salted – our house went through so much salt! Our backyard was always full of wooden crates of salted mackerel, sardines and bonito. Today, you can get such fare at certain seaside tavernas.

I discovered sea urchins when I started venturing out onto the rocks where I went swimming. It took me years to learn how to prise them open with a knife to extract their coral-colored caviar – best eaten on the spot, your feet still in the water. I also remember amazing feasts of mussels from Olympiada. Fresh from the sea, they would go straight into the oven on low so they’d open up and release their juices. We’d drizzle some white wine or ouzo over them and then dish them out. They were so delicious we wouldn’t even bother with salad or bread; just the mussels that smelled of the sea.

I remember how excited I was ferreting around our vegetable garden, replete in the summer with tomatoes, cucumbers, eggplants and peppers. Purslane, that miraculous weed, sprouted everywhere. We used it in salads; with a drizzle of vinegar, it is simply delicious.

The olive harvest is an annual family event.

© Stella Spanou

“Every part of the region has its own special recipes, many of which have survived for centuries.”

I always enjoyed the harvest and was often scolded by my mother for climbing up fig and walnut trees in my white pants.

Halkidiki, in short, gave me the stimulus, cultivated my innate curiosity and helped me become the cookbook writer and chef I am today.

Researching my book on the cuisine of Halkidiki, I was reminded of its splendor. I explored every corner of the peninsula and met with so many people who shared their food, their tsipouro and their stories. Every part of the region has its own special recipes, many of which have survived for centuries. The locals, be they refugees from Asia Minor or the monks of Mt Athos, all added their own personal touch to the great melting pot of Halkidiki’s traditional cuisine, helped by the abundance of fresh ingredients from the earth and the sea that this region so bountifully proffers. The locals, for example, love meat cooked with fruit and vegetables: in winter they prepare a stew of pork with quince and plums; in spring it’s lamb with wild greens or raisins; in summer, billy goat with eggplant. The Anatolians have a fondness for fish, either baked with tomato or prepared with an egg-lemon sauce, and seafood meze in general. The monks of Mt Athos create dishes of marvelous simplicity with vegetables, pulses and all sorts of fish. Their eggplant dip – made of roasted and pureed eggplant and peppers, with a hint of garlic and a dash of olive oil – is an ode to humble ingredients, rich in flavor and nutritional goodness.

A beekeeper smokes his hives to avoid being stung as he collects the honey.

© Stella Spanou

The leaves of the sultana grapevine are the key ingredient in the dolmades (stuffed vine leaves) of Neo Gonia.

© Stella Spanou

Livestock farming is still very much alive and kicking in the area.

© Stella Spanou

To my great joy and surprise, I discovered local delicacies and flavors I had not known. For example, in Nea Fokea, the tourist village on the eastern coast of Kassandra, they still make a pasta known as syrto or “dragged,” because each small chunk of dough is dragged or rolled across the work surface to give it the desired shape. The cook will then poke a small well in the center, which is filled with grated cheese and hot butter when served. My visit to Ammouliani, a small islet settled mainly by folk hailing from Asia Minor, was another revelation. I was escorted by the captain of the ferryboat and as soon as I arrived, local women started coming down to the port – as though summoned by a secret signal – laden with dishes and eager to show off their specialties. I tasted some amazing recipes that aren’t prepared anywhere else in Halkidiki: dainty almond biscuits, fish cakes scented with mint, sweet halva made with bulgur wheat, mackerel stuffed with tomato and herbs…

I visited all sorts of villages where I tried all sorts of pies cooked in the typical Macedonian way; stuffed with fragrant herbs and a handful of rice to absorb excess liquid during baking. I also tried many variations of the “naked” pie, called this because there’s no filo pastry involved; instead, it’s a sort of soufflé made with flour or semolina. This pie is usually savory, with lots of cheese, eggs and grated zucchini.

Last but not least, I must mention a local delicacy that testifies to the region’s deep connection with its grapevines, from which nothing goes to waste: they yield excellent wine, pickled sprouts, grape molasses and, of course, leaves that are used as a wrap for classic dolmades, stuffed with rice and herbs, a particular specialty of Nea Gonia.

The villages of Halkidiki celebrate their natural bounty, mostly in the summer, with festivals: in Nikiti, for honey; in Nea Moudiana for sardines; in Metaggitsi for olive oil; in Porto Koufo for tuna; in Olympiada for mussels. These festivals are usually a combination of party and church fair, where the locals also express their thanks to the saints that grant them protection. They can be loud, bawdy affairs, where playful ribbing and self-sarcasm are considered de rigueur. These Dionysian feasts, where food and goodwill are shared in equal measure, bring people closer to nature and celebrate local traditions, in what is an intrinsic part of this region’s gastronomic and cultural legacy.

At church fairs, the star of the show is usually meat (most often goat). It is cooked overnight on the eve of the feast, with spices and sauces added gradually. The meat is then removed on the morning of the feast and the rye or bulgur cooked in the remaining sauce. The priest blesses the dish after the church service so it can be served. During Lent, seafood, such as octopus or squid, take the place of meat and are served with pulses or rice.

A journey through Greece’s living heritage,...

This comforting, aromatic, traditional meatball soup...

A Thessaloniki expert selects 13 spots...

Cretan cuisine lives on from home...