The Secrets of Sfendoni Cave in the Heart...

From Neolithic findings to haunting legends,...

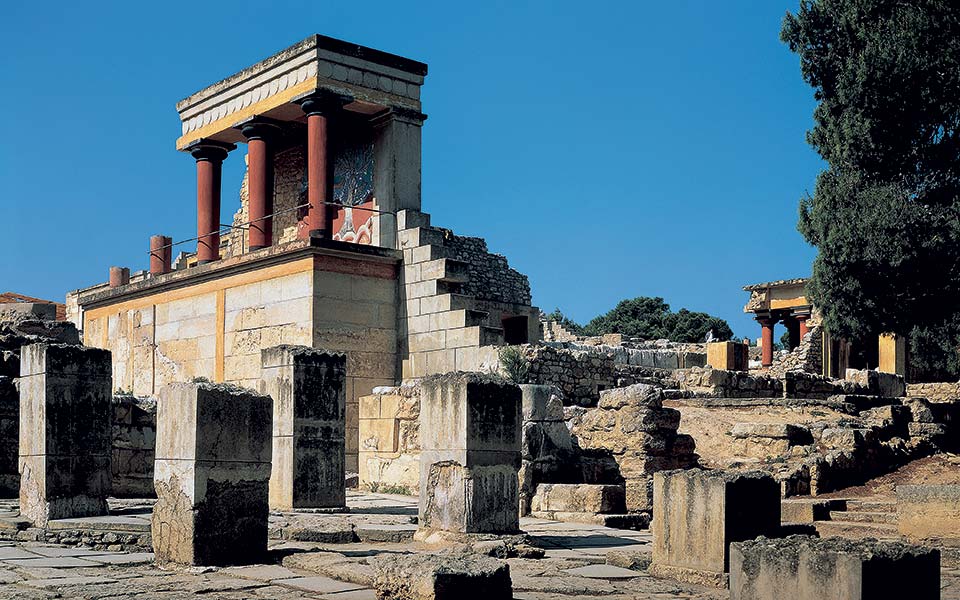

The Customs House (North Wing), overlooked by the reconstructed West Bastion; North Lustral Basin visible in background.

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

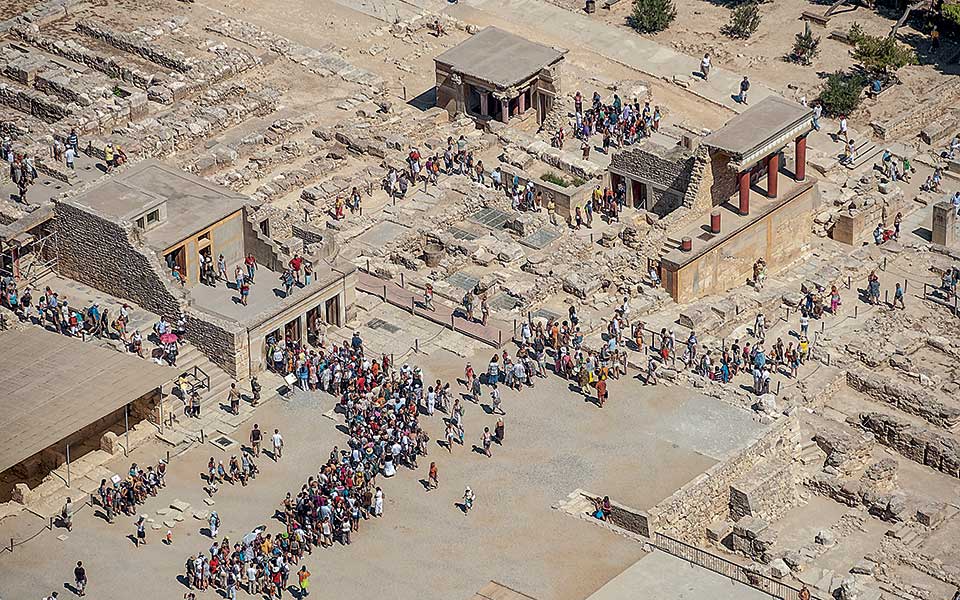

Knossos is Greece’s most popular, best-known archaeological destination after the Athens Acropolis, which means it pays to visit Knossos when there aren’t too many other visitors.

Today, the early morning sun is already warm and bright, but here inside the gate, as I follow the paths channeling us toward the ruins, there is cool shade beneath the fragrant pines.

In many ways, Knossos is where it all started. From this relatively small spot, what came to be Europe’s first major civilization was born around 2200 BC, and gradually spread to impact the culture and economies of Bronze Age settlements across the Aegean Sea. Eventually, Minoan influence was felt from Italian waters to the shores of the Levant and Egypt.

Knossos was the capital of Minoan Crete, a north-coast stronghold that controlled the smaller “palaces” and settlements on the island. It was also an architectural model for some outlying communities, with smaller, similarly designed structures.

The combination of staircases, columns and light is a feature of Minoan architecture.

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

Crossing the West Court, I am reminded by a bronze bust of Sir Arthur Evans that Knossos is also where Minoan archaeology was “invented,” some 12 to 14 decades ago. The site’s archaeological and restorational history has come to be nearly as significant as its cultural history.

This was the conspicuous, artifact-laden mound where a young Evans, tracing the origin of mysterious seal-stones and inspired by Heinrich Schliemann’s earlier discoveries, began unearthing in 1900 what he later dubbed the Palace of Minos.

Dolphins and other marine life adorn the walls of the Quenn’s Megaron (1600-1450 BC).

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

Passing exterior grain pits, a paved courtyard crossed by distinct stone paths and a western wall resting on large orthostate blocks, I recall these are features echoed at Phaistos, Malia, Zakros and other palaces. Other typically Minoan attributes include light wells, sunken “lustral baths,” storage areas, residential spaces that could be opened up and then closed, central courts, stepped theatral areas, multiple stories and flat roofs.

In antiquity, I would have been approaching a massive structure, something like an enormous modern apartment building, or a complex of many adjoining buildings around an open court.

I enter through the South Propylaea, past the reconstructed Procession Fresco and a Minoan column that diminishes downward in diameter. Nearby is the colorfully restored Prince of the Lilies Fresco and the famous Horns of Consecration – identified by Evans as a central symbol of the bull-loving Minoans.

Along the way, details stand out: the texture of the rebuilt walls – representing the original rubble-and-timber masonry designed to be earthquake-resistant; large storage jars, decorated with relief-molded bands and undulating snake-like motifs; and massive amounts of modern concrete used in reconstructed floors, stairwells, walls and ceilings.

Visitors exploring the Central Court, Throne Room, sacred repositories and narrow passages leading into the North Wing.

© Giannis Giannelos

I ascend to the “Piano Nobile,” overlooking the Central Court on its west side. On the left, below, are the storage magazines – a row of narrow spaces equipped with in-ground vaults just inside their entrances. To the right lies the courtyard-heart of the palace. On its opposite side, a long, finely built staircase rises to nowhere, a clear indication of upper floors that once existed. Steps also lead down into this East Wing, where the royal residences could be found. Glancing ahead, I see the North Wing of the Palace, also waiting to be explored.

Snaking my way through partial doorways, I enter a small room reconstructed above the ground-floor Throne Room. Its walls are decorated with prints of the various wall paintings that used to enliven the palace’s interior. Here are bull-leapers; elegant, curly-haired Minoan ladies; a long-tailed blue monkey; a blue bird; and scenes of court life (the originals are now in the Heraklion Archaeological Museum). Dominating the space is a deep light well lined with black and red Minoan columns, providing natural illumination to the lower floor.

Descending the broad western staircase into the Central Court, I step into the vestibule that precedes the Throne Room. This suite of royal rooms is unique to Knossos, and iconic of the essential role Evans’ interpretations have played in shaping what we see at Knossos today. Archaeology is interpretation, and nowhere is that likely to be truer than at this site.

Sir Arthur Evans, holding the famous Bull’s Head rhyton used for sacrificial libations.

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

The Horns of Consecration, near the palace’s southern entrance, a favorite symbol of the Minoans.

© Berthold Steinhilber/laif

To understand Knossos and what we often read about the Minoans, we have to consider the social and political environment in which Evans became acquainted with Crete. As a young man with wanderlust in the 1870s, Evans had traveled through the dying Ottoman Empire’s European territories, where local Christians were rising up against their Muslim overlords.

Soon recognized for his knowledge of the region, he was hired to report on the Balkans for the Manchester Guardian (1877). During this period, he opposed the heavy-handedness of both the Ottoman and Austro-Hungarian governments.

Arriving in Crete in 1894, Evans witnessed more intercommunal strife, as Muslim-Christian tensions, percolating since at least the 1860s, bloodily re-erupted in 1895-1898.

At the same time, the women’s movement for social reform and greater economic and political equality was gaining steam. Historian Cathy Gere (2009) writes that from the 1860s, Darwinism and feminism together made patriarchy questionable and matriarchy possible; and “the island of Crete occupied a privileged place in these speculations.”

Since Herodotus, Crete had been identified as the origin of the Lycians, who took their names from their mothers. What’s more, ancient writers also referred to the island as a “motherland,” not “fatherland.”

The Throne Room, with its alabaster seat for “King Minos” and its reconstructed frescoes of griffins, symbols of power.

© Berthold Steinhilber/laif

Evans came to his excavations at Knossos with an acute awareness of the sociopolitical developments of the time, and an appreciation for Schliemann’s success in finding “Agamemnon” at Mycenae. His own approach was to celebrate Knossos as a nexus of ancient Cretan myths, whose protagonists were familiar to the modern public. Most important for him was “fair-tressed” Ariadne, King Minos’ daughter, for whom Daedalus, the great inventor, had fashioned a dancing floor at Knossos.

When Evans observed the unearthing of the Throne Room, on April 13, 1900, Gere recalls, the alabaster seat against the wall and lustral basin opposite were immediately identified – and recorded in his excavation diary – as the “Throne of Ariadne” and “Queen Ariadne’s bath.” Although he soon reassigned his newfound monarchy to King Minos, the iconographic evidence in Crete for a central female deity encouraged Evans to construct, Gere notes, “a thoroughly modernist female archetype, the Cretan Great Mother: primitive and yet complex, nurturing, powerful and fecund.”

The Minoans’ Great Goddess was later further defined by Jane Harrison, a classicist and suffragist, who, writing in 1922, described a Minoan seal: the Mountain Mother, guarded by lions, “standing with her scepter or lance extended, imperious, dominant.”

It was in the midst of this turbulent milieu of war and feminism that Evans hypothesized his pacifist, female-dominated, yet politically male-led Minoan Crete. So successful was he in highlighting the “more benign aspects of Cretan mythology,” Gere suggests, “that Mycenae and Knossos eventually came to be seen as opposite extremes, one militaristic and patriarchal, the other peaceful and feminine.”

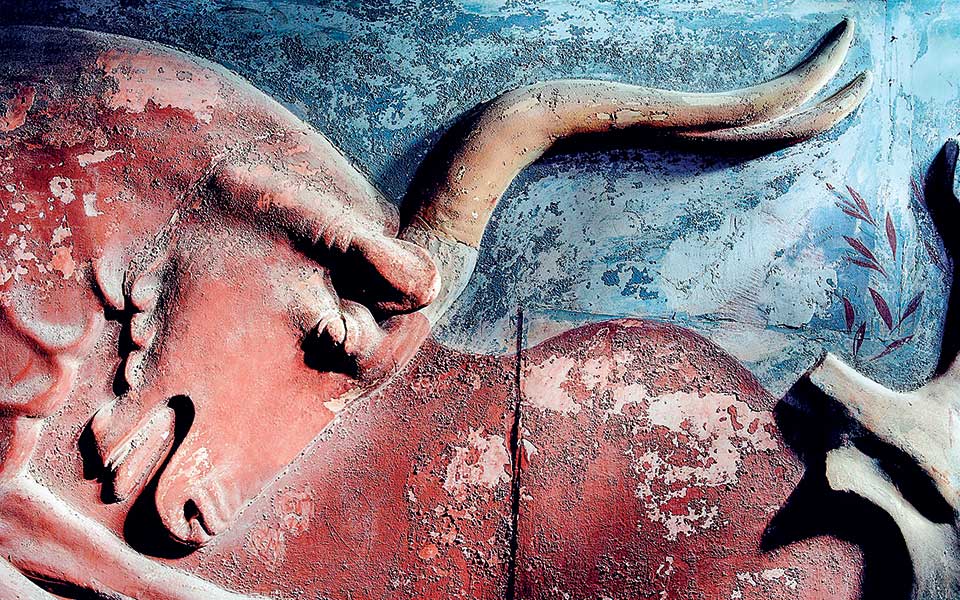

Detail of the reconstructed Bull Fresco in the West Bastion. It was found in fragments in the north corridor.

© Berthold Steinhilber/laif

Leaving the cool gloom of the Throne Room, I return to the sunlit Central Court, known in myth as the lair of the monstrous Minotaur.

On its west side, Evans discovered in sacred repositories two Knossos Snake Goddess (or Priestess) figurines. Below, to the east, the walls of the Queen’s Megaron are decorated with leaping blue dolphins and ornately patterned borders, and the roof is supported on sturdy Minoan columns.

The pier-and-door design, outlined on the floor, allowed an open and breezy room in warmer months that could be closed off with folding doors in wintertime, when freestanding braziers were used for heat. The Minoans even had indoor bathrooms with a plumbing system of clay pipes and stone-built channels.

I decide next to wander through the palace’s northeastern section, past workshops where potters, plasterers and stone carvers once worked. A room lined with benches, identified as a school for scribes, was the find-spot of the famous Bull-Leaping Fresco, fallen from the story above.

Then, entering the North Wing, I “discover” the Customs House, where goods arriving at the palace from near and far were checked; the North Entrance Corridor, with its impressively reconstructed western bastion and bull fresco; and the colonnaded North Lustral Basin.

These enormous jars, once filled with grain, wine, oil and other foodstuff, stand in a storeroom in the palace’s northeastern section

© GETTY IMAGES/IDEAL IMAGE

Viewing Knossos actually gives us only a glimpse of a small fraction of ancient Minoan society. Only 2 percent of the full city of Knossos has been excavated so far!

Archaeologist Kostis Christakis suggests Knossos in the New Palace period (16th-15th centuries BC) had 25,000-30,000 inhabitants, more than Venetian Irakleio. Today, researchers are looking more closely at ordinary Minoans, on whose productivity the Knossian elites depended.

Nevertheless, Knossos remains a monument to far-reaching Minoan power and innovation, as well as to Minoan archaeology’s myth-loving, similarly innovative founder. Evans’ extensive reconstructions may be controversial today, but in this, too, he was “au courant” – he began using internally reinforced concrete at Knossos in the 1920s, shortly after this revolutionary new material was introduced to ancient restoration by Nikolaos Balanos in his work on the Athenian Acropolis.

From Neolithic findings to haunting legends,...

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...

Discover Crete’s iconic sarikopites – delicate...