Walking around the Athenian Agora today, it’s easy to forget, in the midst of this tranquil, tree-shaded archaeological park, that it was once the bustling “Syntagma Square” of its time.

It represented the heart of ancient Athens – not so much because of the governmental, judicial, religious or other public buildings whose remains are preserved, but because of the people who regularly gathered there.

Athens’ citizenry and visitors were the district’s life blood, flowing every day through its narrow lanes and broad Panathenaic Way as they shopped, hurried to court, participated in democratic tasks, or paused to pray at an altar, chat with an acquaintance, or read the inscription on an official stele or a newly erected statue.

© Shutterstock

The Agora Puzzle

In a recent lecture at the American School of Classical Studies (“Hunting Heroes: Recent Excavations in the Athenian Agora”), the long-time director of the Agora investigations, archaeologist John Camp, demonstrated once again that the site of Athens’ former center is not simply a showcase for historically significant architectural ruins, but a complex, fascinating puzzle – one whose pieces, still being found and assembled, can delightfully reacquaint us with the ancient Agora’s human occupants and the contemporary heroes they chose to celebrate.

The present serenity of the Athenian Agora also belies the nearly nine decades of furious effort spent in unearthing this vast archaeological site. Since 1931, generations of excavators seeking clues to the Agora’s ancient topography have had to remove an accumulated overburden 5-8 m thick in places, not to mention some 400 modern houses, a church and other structures that once densely occupied the area.

Camp’s involvement with the project began as an archaeological supervisor in 1966, eventually leading to his appointment as director in 1994. As the longest-serving Agora director, he has overseen many great discoveries all around the former public square.

© Source: American School of Classical Studies

In the Shadow of the Painted Stoa

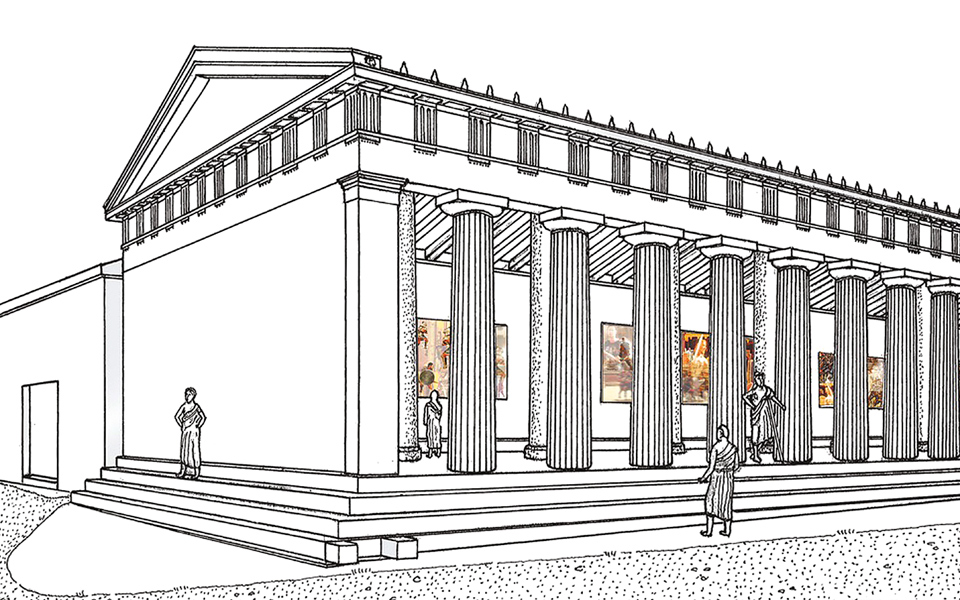

One sector of particular interest has been the site’s northern quarter, dominated by the Stoa Poikile, or Painted Stoa. This rectangular, roofed portico, open on the south where people could freely enter through a Doric colonnade, served no specific official function, but was, in some sense, according to Camp, the most public building in ancient Athens.

Constructed sometime after 475 BC, it famously housed paintings on wooden panels, by Polygnotos, Mikon and Panainos, depicting the Greeks’ real and legendary victories over the Persians at Marathon, the Amazons, the Trojans and the Spartans.

Also displayed in or on the building were commemorative items of war booty, including a series of bronze shields seized during the Athenians’ defeat of the Spartans at Sphakteria island (Pylos) in 425/4 BC.

© John Camp

Through the years, the Stoa Poikile and the area in front of it, much like Monastiraki Square nowadays, was a scene of great and diverse activity, where the attention of crowds or passersby was competed for by a colorful spectrum of street performers, idlers and merchants, from sword-swallowers and jugglers to beggars and fishmongers.

Although occasionally used for religious, governmental or judicial purposes, the stoa was also the haunt of philosophers, most notably Zeno (ca. 300 BC), whose followers became known as “Stoics”.

Sculpture Gallery

With all of the public commotion swirling around the Stoa Poikile, its partly paved forecourt – beneath which the canalized Eridanos river flowed – quickly became a desirable, highly visible space for the display of statues honoring the city’s local heroes, great military leaders and much-appreciated benefactors.

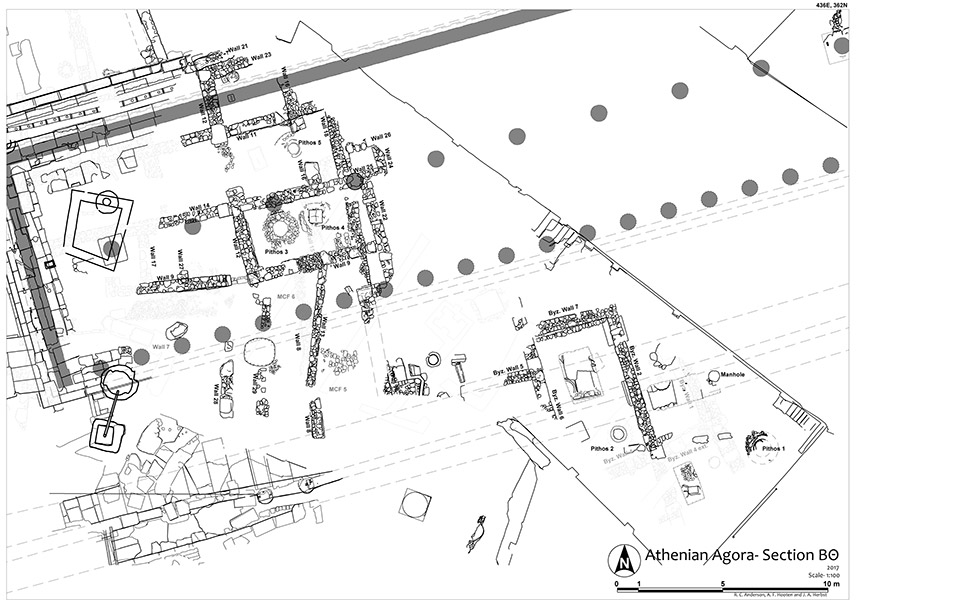

Evidence of this open-air sculpture gallery came to light in 2010, when excavators unearthed a marble trophy base depicting a pile of military spoils: Macedonian shields and other weapons. A cutting on top had secured a statue, probably a victorious Roman general.

In 2013, Camp reports, a second base was found nearby, on the south side of the Eridanos. This white-marble block, reused several times, bears two inscriptions: a partly cut-away Hellenistic dedication (late 4th cent. BC) honoring Athens’ “prytanes” or executive Boule councilors; and a well-preserved Roman text (late 1st cent. BC) announcing that the members of Attica’s Leontis tribe had erected a statue in honor of Eukles, son of Herodes of Marathon.

“Two inscriptions…are more than twice as good as one.”

The Eukles statue base remained in situ and only partly excavated until the summer of 2018. Then, as Camp related, the small probe trench that had first revealed the block was expanded and the base’s larger surrounding context unveiled.

After removing an upper layer of Byzantine remains, archaeologists discovered the Eukles base had been incorporated as building material into the wall of a makeshift Late Roman water basin, itself constructed against the earlier walls of a rectangular “enclosure” or “temenos.”

Another recycled, inscribed statue base bearing a reference to the Leontis tribe was also unearthed near the Eukles base, but has not yet been published. Camp, noting the proximity of the two inscribed bases, recalled a wise adage from archaeologist Eugene Vanderpool: that two inscriptions – concerning a particular subject and found in the same area – are more than twice as good as one.

Thus, it seems, the Leontis tribe played some significant role in the life of the northern Agora.

© John Camp

A Philanthropic Family

Who was Eukles (IV), and why did members of the Leontis tribe erect a statue honoring this non-member of their tribe, declaring him to be a hero? Eukles, his father Herodes and his son Polycharmos the archon were all members of a wealthy, respected Marathonian family. His descendant Herodes Atticus (AD 101-177) ultimately sponsored the construction of the odeon (music hall) on the South Slope of the Acropolis, as well as the renovation of the 4th-century BC Panathenaic stadium (“Kalimarmaro”).

Eukles himself led an Athenian delegation to Rome in the late 1st century AD, which secured additional funding for completion of the city’s new Roman Agora. His name appears, along with those of Julius Caesar and Augustus, in the dedicatory inscription on the Doric gateway of Athena Archegetis, at the western entrance to the Roman Agora.

It seems the Leontis tribe wished to further acknowledge Eukles by honoring him with a statue on an inscribed base in front of the Stoa Poikile – an area of the Agora immediately adjacent to city territory belonging to their Skambonidai Deme.

In assembling the latest part of the Agora puzzle, two further pieces of epigraphic evidence from the vicinity of the Stoa Poikile can be added to the picture, also indicating the Leontis tribe’s particular presence and prestige in the northern Agora.

© John Camp

Triumphant Riders

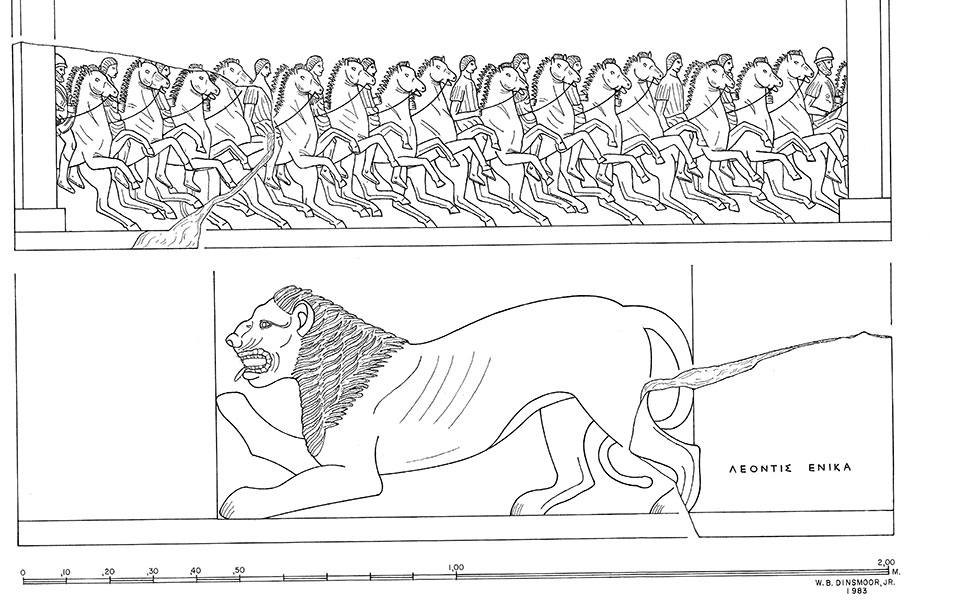

In 1970, just west of the Stoa Poikile, a fragmentary block was discovered, bearing an elegant relief of an equestrian event identified as the “anthippasia”, a mock cavalry fight in which teams of horsemen demonstrated their skills.

On the reverse is carved an inscription, “LEONTIS ENIKA,” signifying that the Leontis tribe, sometime in the early 4th century BC, had won this Panathenaic event. This sculpted, inscribed block, also reused in a Late Roman wall, originally belonged to a public monument that possibly stood, suggests art historian Mark Stansbury-O’Donnel, at the Agora’s northwestern entrance, near which the contest was held.

© John Camp

Heroic Daughters

In the opposite direction, no more than 25m southeast of the Stoa Poikile, another inscription was recorded in 1835 by archaeologist, Kyriakos Pittakis. Searching for the location of the Leokoreion, a famous shrine dedicated to the mythical daughters of Leos who had sacrificed themselves for Athens during a plague or famine, Pittakis writes: “I believe this building was in this place where is the church of St. Philip, because I observed lots of traces there, and on one fragment this inscription: ‘…odemos… Melanippou… Leokoreioi…’”

Now a well-known Plaka landmark, the 19th-century Agios Philippos Vlassarous church, overlying a ruined Byzantine chapel, thus also appears to mark pre-Christian sacred ground: where the Leontis tribe had founded the Leokoreion – one of the Agora’s most legendary monuments.

Famous Assassins

The fame of the Leokoreion shrine stemmed from its association with the assassination of the tyrant Hipparchus in 514 BC, said to have taken place there (Thucydides, 6.57). Hipparchus’ killers, Harmodius and Aristogeiton, known as the Tyrannicides, became local heroes, whose images can still be seen in red-figure vase paintings, copied Roman sculptures and other art.

The original statue group depicting the pair, crafted in bronze by the sculptor Antenor (ca. 510 BC), represented Athens’ first honorary, publicly commissioned statues – erected within the Agora, probably in a spot, Camp believes, very near the Leokoreion, the scene of their crime.

Despite their being stolen by Persian invaders in 480 BC and carried off to Susa, the bronze Tyrannicides were eventually returned to Athens, where, alongside replacement copies made during their absence by Kritios (477 BC), they continued to stand until at least the mid-2nd century AD when the traveler Pausanias (1.8.5) observed all four.

A fragmentary epigram referring to Harmodius and Aristogeiton, attributed by archaeologists to the base of the later statue group, was found in the Agora in 1936, about 50 m south of the 2018 excavation site.

© John Camp

A Mystery Solved?

Camp’s presentation of Athenian Agora heroes – from an unknown Roman general to Eukles, the victorious Leontis riders, the daughters of Leos and the Tyrannicides – culminated with his cautious conclusion that a longstanding mystery may finally have been solved. Although further digging is necessary, we already have a constellation of architectural, historical and especially epigraphic evidence that highlights the major civic role of the Leontis tribe in the northern Agora.

In addition, one now has to wonder if the Leokoreion, established by the followers of Leos, still lies waiting to be discovered, somewhere in the unexcavated area between the Stoa Poikile and the church of St. Philip. Only continued archaeological investigation can answer this intriguing question.