As the dust settles from the recent US presidential election, with questions of leadership and citizen involvement fresh on our minds, it seems timely to reflect on the origins and early development of democratic governance. How did the first democracy function, and what can it teach us today?

Imagine stepping back in time to the bustling city of ancient Athens, walking through the Agora as the hum of debate fills the air. Over 2,500 years ago, this Greek city-state—or “polis”—took a radical leap: citizens—ordinary people, not kings or aristocrats—would govern their society. This was democracy, but democracy with a direct twist: one where citizens were expected to actively participate in public life.

Join us as we explore how ancient Athenian democracy worked, its core institutions, and the bold demands it placed on its citizens.

The Birth and Evolution of Athenian Democracy

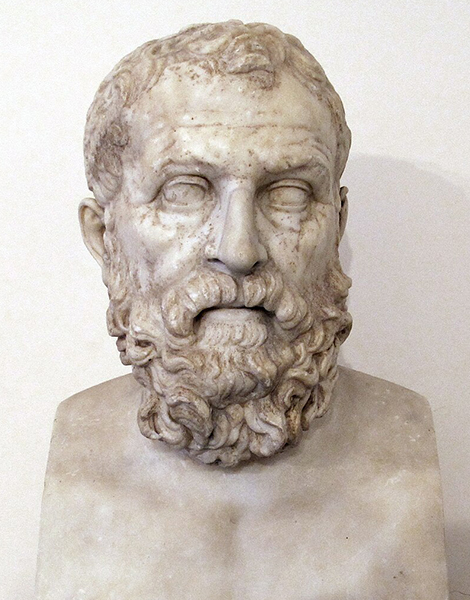

It may seem obvious to say, but Athenian democracy—“demokratia,” meaning “people’s rule”—didn’t emerge overnight. It began with the great reformer Solon (c. 630 – c. 560 BC) in the early 6th century BC, during a time of great social and economic unrest. Land ownership and wealth disparities threatened social stability, with many poor citizens falling into debt slavery. Solon’s reforms addressed these issues head-on, canceling debts and freeing Athenians enslaved due to financial obligations. He was later described by the 4th century BC philosopher Aristotle in the Athenian Constitution as “the first people’s champion.”

Solon also introduced a four-class system based on wealth, which, while still unequal, allowed some political and administrative roles to be filled by citizens beyond the traditional aristocracy. These changes stabilized the social structure of Athens, laying the groundwork for wider citizen participation in the day-to-day running of the state.

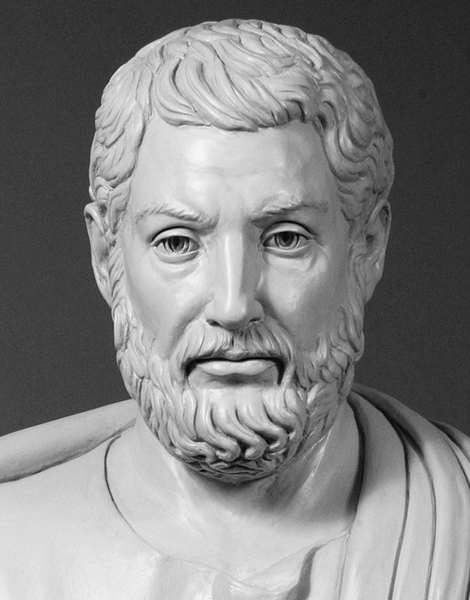

The true architect of Athenian democracy, however, was Cleisthenes (c. 570 – c. 508 BC), whose reforms in 508 BC transformed the city’s political landscape. To limit the power of aristocratic families, he organized society into ten tribes made up of local units called “demes,” creating a political identity based on residence rather than family. This revolutionary move diluted the influence of powerful families, shifting focus from hereditary power to regional representation; in other words, the people’s political identity was based on where they lived, not on family ties. Cleisthenes’ tribal system ensured that no single faction could dominate the government, making Athens a true “democracy”—a rule of the people rather than of the few.

Solon’s and Cleisthenes’ reforms opened the door to unprecedented citizen participation, creating a model of direct democracy where the people themselves, not elected representatives, would make crucial decisions.

© Dionysis Kouris

The Ekklesia and Boule: Direct Democracy in Action

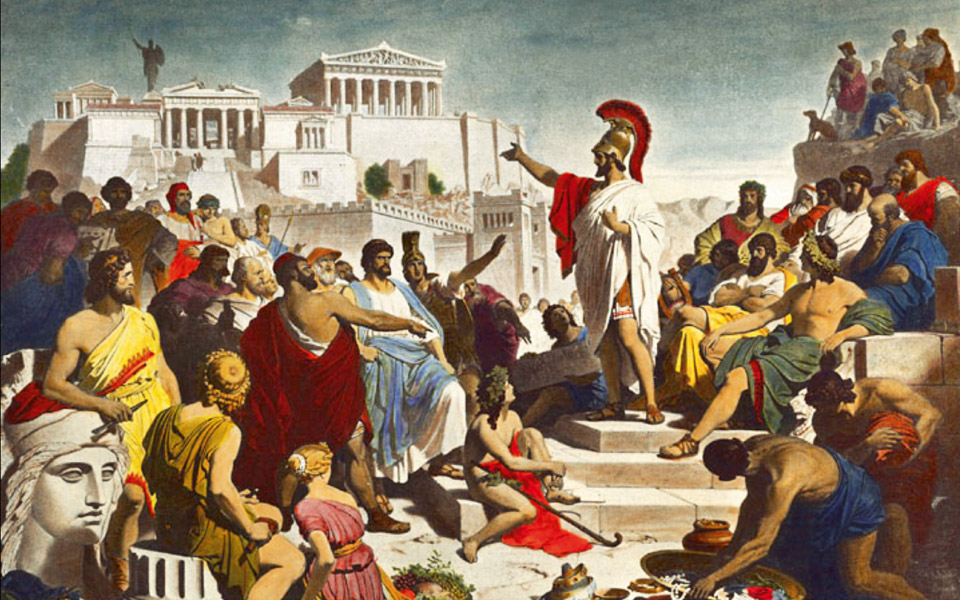

At the core of Athenian democracy was the “Ekklesia,” or Citizen Assembly, a governing body that embodied the principle of direct participation. Open to all adult male citizens—as many as 60,000 in the mid-5th century BC—the Assembly was where Athenians could speak and vote on matters directly affecting the polis. Unlike modern systems where elected representatives debate and vote in parliament, Athenian democracy required citizens to actively engage in decision-making themselves.

The Assembly met around 40 times a year on the Pnyx Hill, a large open area west of the Acropolis that could accommodate thousands (with historians estimating a seating capacity between 6,000 and 13,000). Topics ranged from military campaigns to public spending, alliances, and laws, with each decision determined by majority vote. Voting methods included raising hands, counting stones, using broken pottery shards, or placing a pebble into one of two urns to indicate choice.

Supporting the Ekklesia was the “Boule,” or Council of 500, an administrative body selected by lot to prevent elite dominance. This Council prepared the Assembly’s agenda, managed finances, and oversaw civic duties. The 500 members of the Council were divided into ten groups of 50, each group representing one of the ten Attic tribes. Each tribe took turns leading the Boule, ensuring equal representation across Athens.

Roles That Kept Athens Running

Alongside the Ekklesia and Boule, several key roles kept Athens’ democracy functional. The “strategoi” (generals) were the most prominent officials, elected by the people for their military skill—a rare nod to merit in this otherwise egalitarian system. Strategoi oversaw both the military and civic administration of the polis, with influential figures like Pericles (c. 495 – 429 BC) shaping Athens through diplomacy and public leadership. Each year, the Assembly elected ten strategoi, one from each deme.

The “archons” (chief magistrates) were another group of officials who played an important, though more limited, role in Athenian governance. Originally, these magistrates were elite aristocrats with significant power, but as democracy evolved, their influence diminished. By the classical period, archons were selected by lottery, and their primary duties were administrative, ceremonial, and judicial. There were nine archons each year, each with specific responsibilities. For example, the eponymous archon handled public festivals and legal cases, the polemarch oversaw military affairs, and the basileus (or “king archon”) managed religious functions. Though they held these roles for only a year, their functions were essential for the social and religious life of Athens.

Another feature of Athenian governance was the rotating executive committee of the Boule, known as the “Prytaneis.” Each of the ten tribes took turns serving as the Prytaneis for roughly one-tenth of the year. During this period, members of the committee managed day-to-day affairs, convened meetings, and dealt with any immediate concerns affecting the city. The Prytaneis also held an honor unique to Athens: they dined in the Tholos, a round building in the Agora, at the city’s expense, underscoring the dignity and responsibility of their service. This daily rotation of leadership prevented any single tribe from dominating decision-making and emphasized the Athenian ideal of shared power.

© Shutterstock

Who Participated?

While Athenian democracy prided itself on citizen participation, it’s important to understand who actually counted as a “citizen” and how participation was structured. Citizenship came with both rights and obligations, but the qualifications for it were quite specific, making Athenian democracy more exclusive than modern standards might suggest.

In classical Athens, citizenship was restricted to adult males with Athenian parentage on both sides. This requirement excluded most of Athens’ population: women, slaves, and foreign residents, known as “metics.” Metics, though often integral to the Athenian economy as artisans, merchants, and skilled laborers, lacked political rights and could not own land. Similarly, slaves—who made up a significant part of the population—had no political standing, reflecting the deep social hierarchy embedded within Athenian society.

Women were also barred from political life, which was considered the realm of men. Although women could participate in religious rituals and festivals, their influence on public matters was indirect, usually exercised within the family structure.

For those who qualified, Athenian citizenship brought significant privileges, the foremost being participation in the Ekklesia. Citizenship was not merely a title but a role with defined expectations: Athenians believed that democracy required active engagement from all who were eligible, from attending Assembly meetings to serving in public office and even fighting in the city’s defense when needed.

This commitment to civic engagement fostered a culture in which political awareness and involvement were highly valued. Athenians considered it a civic duty to participate in the democratic process; those who did not were seen as shirking their responsibility, which could lead to social stigma and even a fine. In a way, Athenian democracy was as much a collective responsibility as it was a privilege.

“Favoring the Many Instead of the Few”

No exploration of Athenian democracy would be complete without reflecting on Pericles, one of its most influential leaders. In 430 BC, during a state funeral for soldiers who had fallen early in the Peloponnesian War, Pericles delivered a powerful oration, captured by Thucydides.* In this famous speech, known as the Funeral Oration, Pericles articulated a vision of democracy that emphasized individual freedom balanced with collective responsibility.

He declared, “Our constitution does not copy the laws of neighboring states; we are rather a pattern to others than imitators ourselves. Its administration favors the many instead of the few; this is why it is called a democracy.” Unlike oligarchies or monarchies of the time, Athenian democracy was driven by the people, not elites. For Pericles, true democracy meant equal opportunity and merit-based advancement, where one’s role in society depended on ability rather than wealth or birth. Though restricted to male citizens, this ideal was groundbreaking in the ancient world.

Pericles praised Athenians for balancing personal freedom with civic duty, a combination that he saw as key to their success. Athenians, he said, “live exactly as we please,” while respecting public law and order. Pericles observed, “We do not feel called upon to be angry with our neighbor for doing what he likes,” but that “all this ease in our private relations does not make us lawless as citizens.” This blend of freedom and responsibility was a core Athenian value and is foundational to modern democratic ideals. For Pericles, active civic participation was essential to a functioning democracy. As he put it, “We regard him who takes no part in these duties not as unambitious but as useless.”

This vision of democracy, which demanded active contribution rather than passive observation, remains one of Pericles’ most enduring legacies. His words challenge modern readers to reflect on the level of commitment and responsibility that democracy requires. Pericles understood that for democracy to thrive, its citizens must be informed, engaged, and willing to prioritize the public good over personal interests.

* Thucydides, “The History of the Peloponnesian War,” London, J.M. Dent; New York, E.P. Dutton. 1910.

Pitfalls and Limitations of Athenian Democracy

While Athenian democracy was pioneering, it was also limited and vulnerable. Despite its radical emphasis on citizen participation, Athenian democracy restricted “citizenship” to adult males with Athenian parents on both sides, excluding women, slaves, and metics (foreign residents). By modern standards, this exclusion undermines the democratic ideal of equality.

The volatility of public opinion also posed challenges. Decisions in the Assembly could be influenced by collective passions, leading to impulsive actions. For instance, in 406 BC, after the naval Battle of Arginusae, the Assembly sentenced six generals to death for failing to recover the bodies of soldiers lost at sea, even though rough weather had made rescue impossible. This decision, later regretted, left Athens without capable leaders during a critical phase of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC).

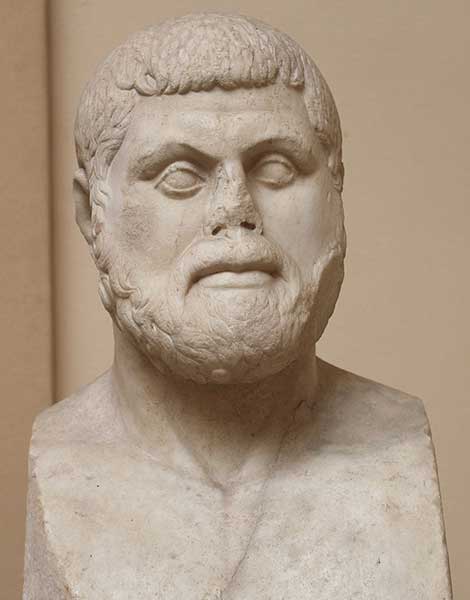

Another vulnerability lay in ostracism, a process that allowed citizens to vote to exile an individual from Athens for a period of ten years. While it was intended to protect against potential tyrants, in practice, however, it could be misused against popular figures due to changing public opinion. Leaders like Themistocles (c. 524 – c. 459 BC), once celebrated as hero of the Battle of Salamis in 480 BC, could be ostracized when opinion turned against them. Athenian democracy was also susceptible to charismatic speakers or demagogues who swayed the Assembly with emotional rhetoric, sometimes to the detriment of reasoned debate and long-term planning.

For more on the limits and weaknesses of the Athenian democracy, click here.

Legacy and Enduring Influence of Athenian Democracy

The democratic experiment in Athens left a lasting mark on political thought, inspiring leaders, thinkers, and societies through the centuries. Despite its flaws, Athenian democracy established foundational principles—such as civic participation, public debate, and accountability—that continue to resonate today.

Throughout history, leaders from the Renaissance to the Enlightenment looked to Athens as an example of popular sovereignty. Thinkers like English philosopher and physician John Locke (1632 – 1704) and the French political philosophers Montesquieu (1689 – 1755) and Jean-Jacques Rousseau (1712 – 1778) praised Athens’ civic duty model, discussing ways to make democratic principles more inclusive. When drafting the American Constitution, the Founding Fathers adapted elements of the Athenian model to a representative system with checks and balances, learning from Athens’ achievements and challenges.

One of Athens’ most enduring contributions is its emphasis on civic responsibility. For Athenian citizens, political participation was both a right and a duty, a concept that continues to inspire democracies today. Public debate, another hallmark of Athenian democracy, also remains integral to modern democratic life, seen in institutions like free press, public forums, and town halls. The Athenians believed open discussion essential for making informed decisions, a value modern democracies around the world still uphold.

While Athenian democracy’s limitations—its narrow definition of citizenship, vulnerability to emotional decisions, and challenges in justice—underscore the need for inclusive and stable structures, they also remind us of the importance of active citizen engagement. As today’s democracies face challenges from polarization and misinformation, Athens’ legacy calls us to reflect on how well we uphold principles of civic engagement and accountability.