Τhe tradition of hospitality is a timeless characteristic of Greek culture. Even today, a visitor’s first contact with Greek lands and people is often memorably colored by the generous hospitality offered by their host. This custom dates back thousands of years, commemorated in the semi-historical pages of the anonymous bard or bards we know as “Homer,” whose frequent descriptions of hospitality highlight the tradition’s religious, social and political functions.

The proper provision of hospitality in ancient Greece was an important ritual that encouraged social, political or military “networking.” It was a sacred responsibility that came under the watchful eye of the Olympian gods. Zeus Xenios, “the strangers’ god,” ruled as hospitality’s chief protector. To behave inhospitably was an offense worthy of divine punishment, as hospitality was governed by a well-known code of conduct with duties for both host and guest.

Regardless of a guest’s identity – king, general, other dignitary, friend, or simple messenger – one had to welcome him with food, drink and shelter before asking any questions. A guest was equally respectful, listening attentively to his host and returning his favor by entertaining the assembled banqueters with his own story.

Diplomacy

From at least the Late Bronze Age and early centuries of the Iron Age, long before any hotels and star-ratings, hospitality thrived in the Eastern Mediterranean and Near East as a vital, ubiquitous practice, a religious duty, a facilitator of commerce and, for elites, of state diplomacy.

The Classical Greek institution of “proxeny, ” wherein city-states selected certain well-to-do citizens to serve as local hosts for foreign ambassadors, also relied on hospitality. A proxenos, like all good hosts, had to have diplomatic skills. Respect was demonstrated by both parties and an exchange of gifts indicated the acceptance or continuance of friendship.

To ensure the longevity of that relationship, hospitality could even be hereditary. Euripides’ fifth-century BC play “Medea,” for instance, reveals that sometimes a host and his guest would exchange a distinctive token that could be redeemed whenever hospitality might again be desired or that could be passed on to the next generation.

© DE AGOSTINI, HULTON ARCHIVE / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

Homeric hospitality

Our ceaseless fascination with Homer’s epic tales arises largely from the window they provide onto the mysterious and mythical yet strangely familiar ways of ancient Greek life. Chief among the array of ancient practices and beliefs described in those works was hospitality.

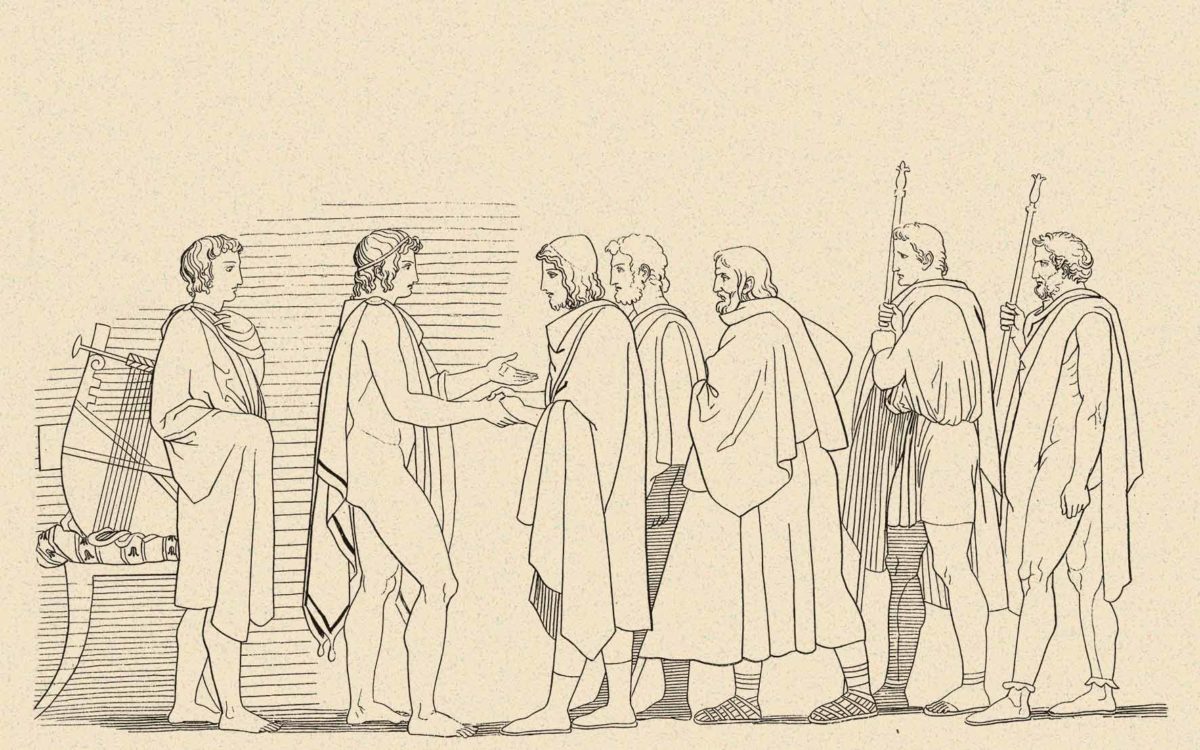

In the Iliad, top-level diplomatic hospitality is demonstrated when Agamemnon dispatches an embassy to the disgruntled Achilles. His ambassadors, Odysseus, Ajax and Phoenix, are received in grand style and offer lavish gifts to Achilles, including: “…seven tripods, that the fire hath not touched, and ten talents of gold and twenty gleaming cauldrons, and twelve strong horses… [Also,]…seven women skilled in goodly handiwork, women of Lesbos…, and amid them…the daughter of Briseus…”

Appropriate hospitality gifts also included finely crafted banquet equipment, such as the drinking cup and krater (mixing jar) presented to Telemachus by King Menelaus in Sparta. Careful planning often went into the act of being hospitable in order to show respect and gain favor – with the best meat, wine and seats selectively offered to acknowledge a guest’s high social status.

Homeric poetry, with its recurring theme of hospitality, was well-suited as dinner time entertainment: providing such amusement to guests was itself an essential element of hospitality. Moreover, the guests were in the midst of enjoying actual hospitality, whose practical code of do’s and don’ts would have been on everyone’s minds at that very moment.

The tale of the Iliad recalls the Trojan War, the Greeks’ reaction to a blatant violation of xenia, the proper conduct for hosts and guest, which occurred when Paris, leaving Sparta, “stole” his host’s wife. The Odyssey, which recounts its protagonist’s tireless search for hospitality on his homeward journey, serves as a vehicle for examining the nature of xenia as well.

At least eighteen scenes of hospitality are found in Homer’s works, philologist Steve Reese reports, including four in the Iliad, twelve in the Odyssey and two in the Homeric Hymns.

These unique scenes, although distinctly Homeric, together reflect a traditional formula for the giving and receiving of hospitality: arrival; the wait at the threshold; the supplication; the reception; the seating; the feast; the after-dinner drink; the identification of the visitor; an exchange of information; entertainment; the visitor’s blessing on the host, the shared libation or sacrifice, the request for sleep; the bed; the bath; the host’s attempts to detain the visitor; the guest-gifts; the departure meal and libation; the farewell blessing; the departure omen and interpretation; and the escort to the visitor’s next destination.

© LOOK AND LEARN / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Playing with convention

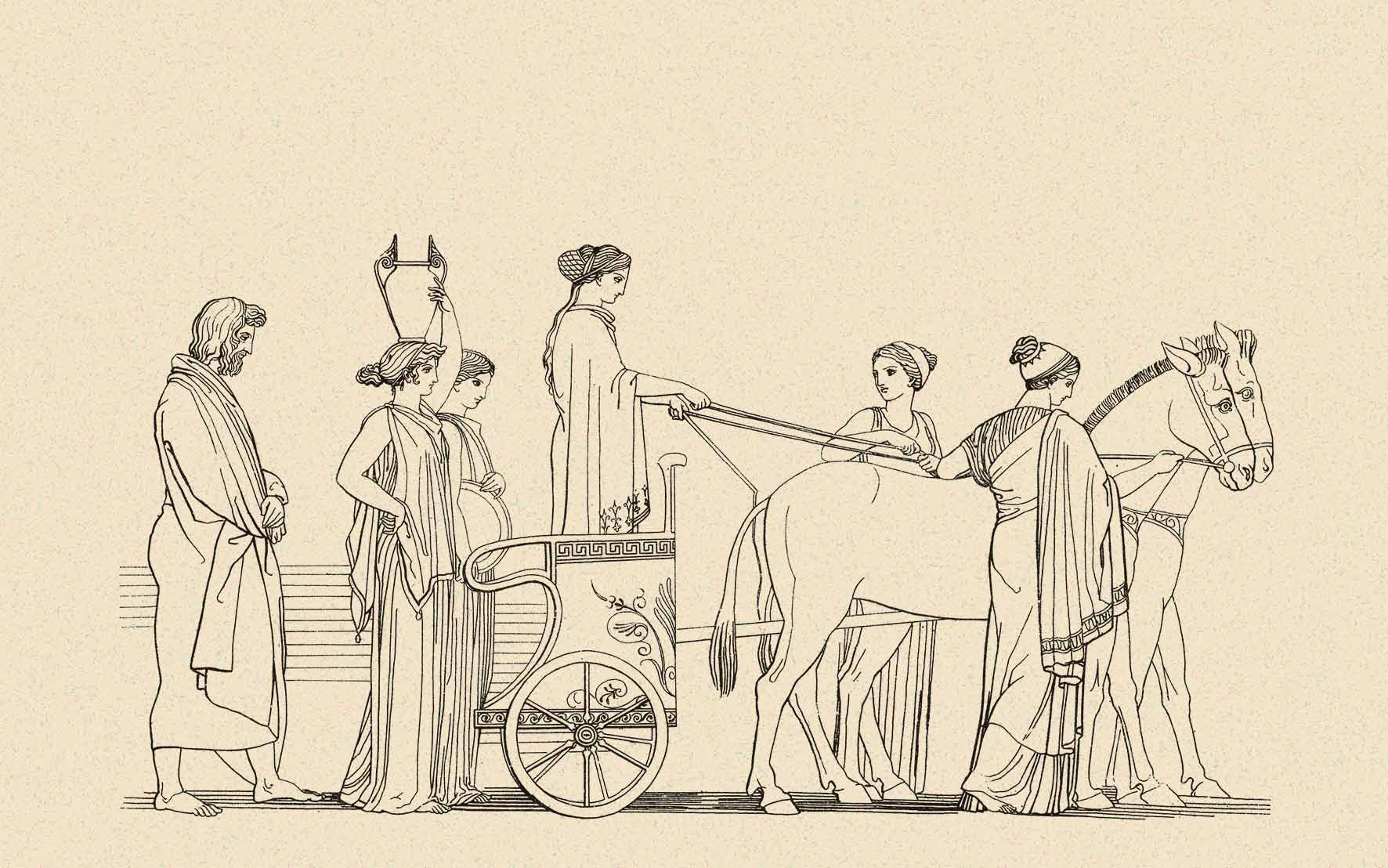

In the Odyssey, a broad spectrum of hospitality is presented, from the generosity of the Phaeacian princess Nausicaa towards Odysseus, or of the swineherd Eumaeus with his near-perfect hosting of his master, to the amoral suitors’ final scene in which all the conventions of hospitality are shockingly inverted.

Along the way, Homer juxtaposes good and bad hospitality, essentially parodying the tradition with colorful characters. The cruel giant Polyphemus, instead of feasting his guests, makes them the feast and offers Odysseus the “gift” of eating him last. The insolent suitor Ctesippus similarly mocks xenia by hurling the “gift” of a hoof at Odysseus.

The ill deeds of both the Cyclops and the suitors epitomize brazen inhospitality, condemned by all, and are later memorialized through Euripides’ artful terms “xenodaites” (he who devours guests) and “xenoktonos” (the slaying of guests and strangers). Nevertheless, the outrageous transgressions of sacred and social responsibility that are featured in Homer’s poems continue to make for humorous, mildly moralizing, ageless entertainment.

Mythical reminders

Hospitality became interwoven with myth and legend in the belief systems of ancient Greeks, Romans and even the early Christians, as mythical or biblical stories were often cautionary reminders that proper rules of conduct should be followed.

To behave inhospitably or to fail to give hospitality was to act contrary to divine will, as King Nestor avows when Athena and “godlike” Telemachus wished to depart from Pylos: “…Nestor…sought to stay them, and…spoke to them, saying: “This may Zeus forbid, and the other immortal gods, that ye should go from my house to your swift ship as from one utterly without raiment and poor, who has not cloaks and blankets… whereon both he and his guests may sleep softly… Never surely shall the dear son of this man Odysseus lie down upon the deck of a ship, while I yet live….”

Gods come calling

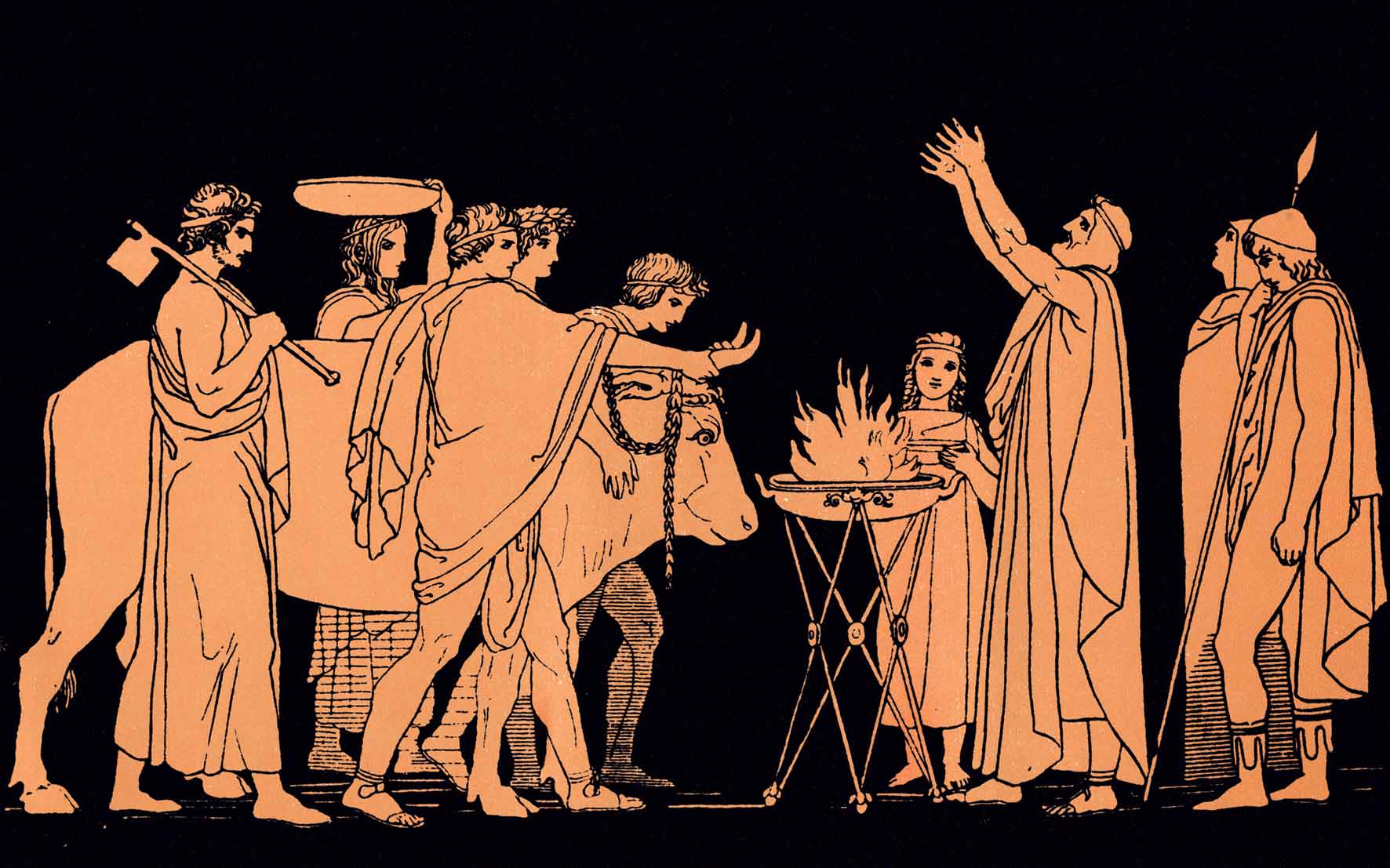

Ancient hospitality was a sacred duty almost akin to a religious sacrifice. Any stranger that “rang the bell” could be a god in disguise, there to test the mortal homeowner’s hospitality.

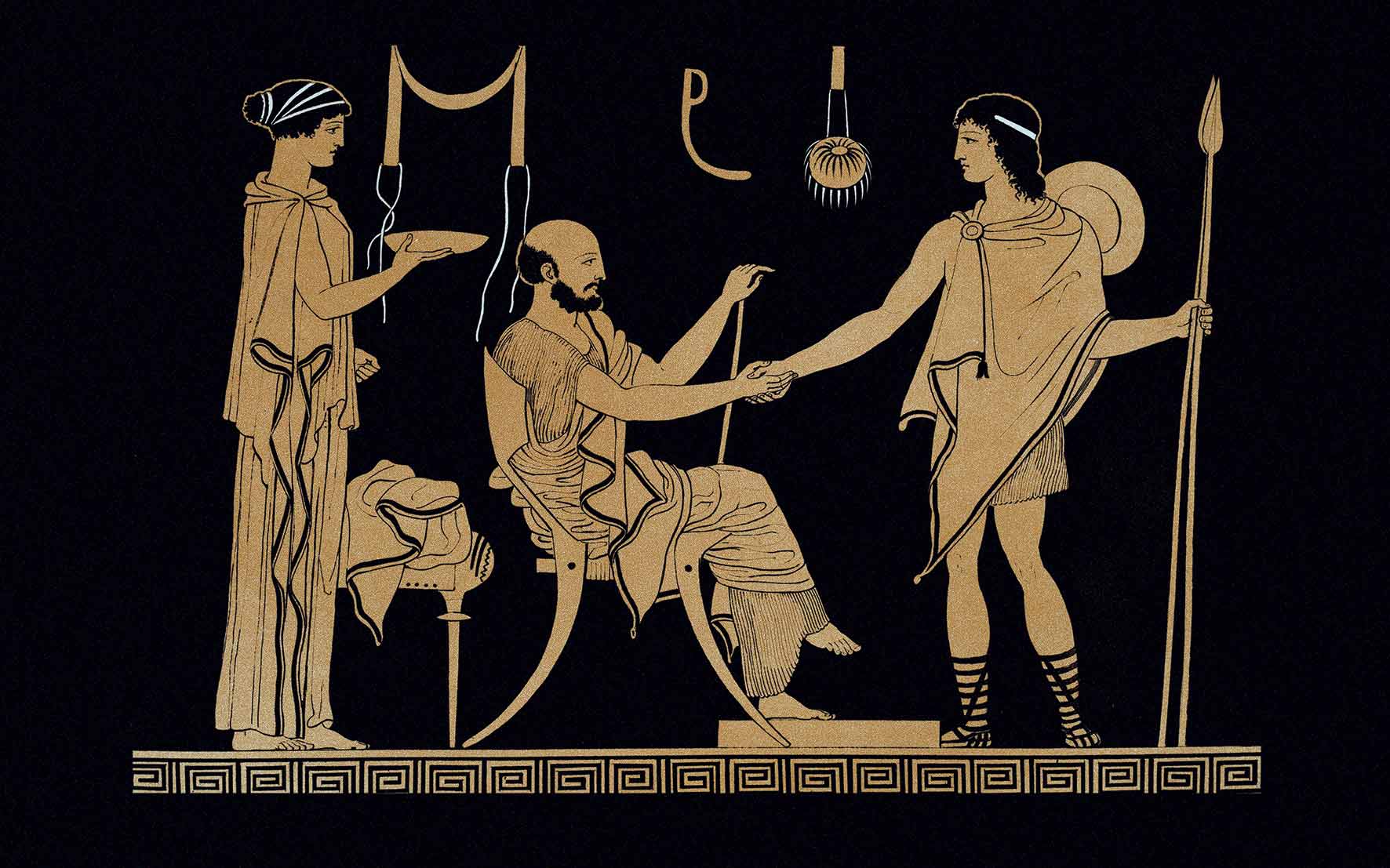

Even apparent friends could be divinities incognito, such as “Mentes,” Odysseus’ old comrade, actually Athena, who is generously received by Telemachus: He beheld Athena, and went straight to the outer door; for in his heart he counted it shame that a stranger should stand long at the gates. So, drawing near, he clasped her right hand, and took from her the spear of bronze; and he spoke, and addressed her with winged words: “Hail, stranger; in our house thou shalt find entertainment and then, when thou hast tasted food, thou shalt tell of what thou hast need.”

All-powerful Zeus, as Zeus Xenios, was hospitality’s divine embodiment, although Hestia, goddess of the hearth and household order, was also linked to the custom. In addition, Hermes, the gods’ herald and Zeus’ personal messenger, assisted the king of the gods in overseeing hospitality and protecting travelers.

© DE AGOSTINI, HULTON ARCHIVE / GETTY IMAGES / IDEAL IMAGE

As basic as the sea…

Mythology showcased the essential role of hospitality in ancient Greek life. The classicists Charles Victor Daremberg and Edmond Saglio wrote that “the itinerant and social nature of…Greeks, the feasts, the needs of trade and very often…the political exiles…render[ed] hospitality…necessary in all parts of the Greek world.”

Hospitality was as basic to the Greek experience as the sea, sky and mountains. Its mythical descriptions were allegories for the pleasure, pain and anxiety inherent to a human world ultimately governed by mysterious, almighty nature.

Hospitality was a suitable medium for the apparition of a god, observes anthropologist Julian Pitt-Rivers, as a stranger at one’s door was nothing less than a confrontation between the familiar, ordinary world and the unknown, unpredictable “extra-ordinary” world. If the potential danger that arrived with a guest was to be avoided, Pitt-Rivers continues, “he must either be denied admittance, chased or enticed away like evil spirits…, or, if granted admittance, he must be socialized.” This happened through ritualized inversion, during which the visitor was transformed from a hostile stranger to a welcome guest.

Hospitality, however humble

Often in ancient myth and literature, the rich and greedy declined to offer a proper welcome, while the poor but generous threw open their humble household to what is later revealed to be a deity. This mythological sub-genre, theoxeny, is given a heroic twist by Homer, notes classicist Bruce Louden, when the poet has “a mortal play the role normally assigned a god.

Odysseus both tests hospitality and exacts punishment on the impious who fail to be hospitable.” In Roman times, Ovid tells the tale of Philemon and Baucis, an elderly couple who welcome Zeus/Jupiter and Hermes/Mercury into their humble home. They go to great lengths to offer their unknown visitors hospitality, even preparing to slaughter their prize goose. Held up as an example of proper host behavior, they are spared from a massive sinkhole that swallows their entire neighborhood, while their house becomes a temple.

A host’s evil scheme

Such cautionary tales abound in antiquity. As was noted earlier, the Trojan War in the Iliad was sparked by the “theft” of a Greek host’s wife, while the Odyssey recounts how a hero returns from that war only to find his wife plagued by would-be suitors abusing his/her hospitality.

A particularly gruesome tale involving Zeus/Jupiter appears in Ovid’s Metamorphoses, where the god as a traveling stranger is put up by King Lycaon of Arcadia. His impious host, however, plots his murder after first serving him flesh from a grilled Molossian hostage. Zeus perceives Lycaon’s evil scheme and decimates his palace with thunderbolts before transforming his bloodthirsty host into a raving, shaggy-haired wolf.

Do unto others…

In Roman times, hospitality became less about a sacred duty to properly welcome a stranger and more about a host’s role in providing for his guests. Nevertheless, in the Christian World, the importance of hospitality as an element of morality continued to be transmitted through religion.

Scholars suggest hospitality is central to virtually all Old Testament ethics. In a passage particularly relevant today, Leviticus 19: 33-34 pronounces: “When a foreigner resides among you in your land, do not mistreat them. The foreigner residing among you must be treated as your native-born. Love them as yourself, for you were foreigners in Egypt.” Ultimately, hospitality in myth and religion manifests the age-old “golden rule”: do unto others as you would have them do unto you.

© LOOK AND LEARN / BRIDGEMAN IMAGES

Laws of hospitality

Hospitality was so important in antiquity that in Classical Athens it even became legally codified. Plato’s Laws record how four types of foreign visitors should be variously received by Athenians, depending on their purpose, position and social status.

Merchants, cultural visitors and civic dignitaries received formal treatment from, respectively, commercial officials, priests and temple custodians, and government representatives. High-status cultural visitors over the age of fifty were welcomed formally, but in a friendlier manner, hosted by equally wise figures, educational officials, or recognized specialists in art and culture. In all cases, both host and guest had certain legal obligations.

Duties end at the door

Hospitality’s rituals and codes have long intrigued anthropologists studying human cultural behavior. “A host is host only on the territory over which on a particular occasion he claims authority,” Pitt-Rivers observes, adding “a guest cannot be guest on ground where he has rights and responsibilities.”

Thus, a host’s courtesy in “showing a guest to the door or the gate underlines a concern in his welfare as long as he is a guest, but it also defines precisely the point at which he ceases to be so, when the host is quit of his responsibility…”

Respect and reciprocity

Although mutual respect was required between hosts and guests, they weren’t considered equals when they met; equality invited rivalry. The guest, whoever he was, had to remain deferential to his host while accepting his hospitality – but with the understanding that the kindness would later be returned, with the guest now in the dominant role.

Key elements of hospitality, then, were reciprocity and alternating roles, even when a host and guest may be bitter enemies – as in the case of King Priam’s visit to Achilles’ tent to request his son’s body.

Obeying the rules

Whether king or beggar, a visitor had to adhere to his duties as a respectful guest. If he violated the rules of hospitality, he returned to the role of hostile stranger. Everyone understood the hospitality code, but sometimes chose to violate it.

In the Odyssey, Menelaus says to Telemachus, “I would condemn any host who…acted excessively hospitable or excessively hostile… It is as blameworthy to urge a guest to leave who does not want to as it is to detain a guest who is eager to leave…” However, both Menelaus and Nestor prevent Telemachus from leaving Sparta and Pylos, thus prolonging his homeward journey.

In the climax of the Odyssey, the rules of hospitality are dramatically reversed, and the sacred tradition polluted; Odysseus’ slaughter of his “guests,” the suitors, is rightful justice, after which order and peace are restored.

This article was originally published in the print magazine Greece Is Philoxenia 2019-2020. To browse or download a digital copy of the magazine click here. Hard copies can also be ordered from anywhere in the world via our e-shop at only the cost of postage and packaging.