As we settle into the heart of winter, with Christmas lights twinkling and the rich aroma of melomakarona and kourabiedes in the air, we thought it would be fun to reflect on how the ancient Greeks faced the season’s dual challenges of hardship and celebration. For them, winter was certainly a time of struggle, as they endured biting winds and stormy seas that halted trade, but it was also a season of resilience, reflection, and shared joy. Central to their traditions was Hestia, goddess of the hearth and home, whose sacred flame offered not only physical warmth but also a powerful sense of unity and connectivity for both households and communities alike.

Exploring Hestia‘s role and the place of the hearth in everyday life in ancient Greece reveals an enduring story of human ingenuity and spirituality. From age-old rituals to the heartwarming traditions of today’s festive season, the glow of the hearth continues to inspire and comfort us through the darkest days of the year.

Who Was Hestia? The Keeper of the Hearth

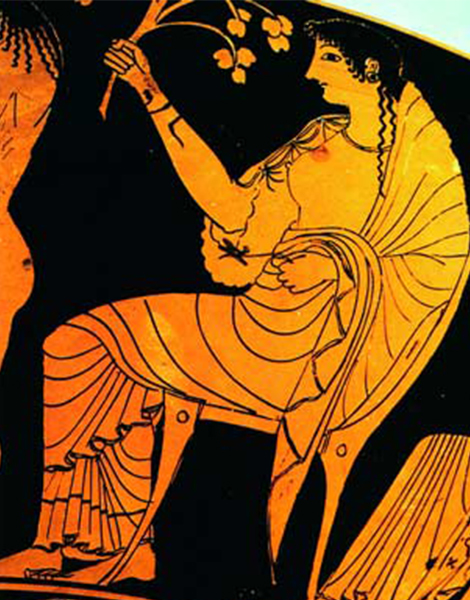

Hestia, one of the twelve Olympian gods, was a figure of quiet, unassuming strength and serenity. As the eldest daughter of the titans Cronus and Rhea, she stood apart from her fiery siblings like Zeus, Hera, and Poseidon. Hestia’s domain was the hearth – the physical and spiritual center of Greek domestic and civic life. Unlike the dramatic tales of her fellow deities, Hestia’s mythology is sparse, reflecting her peaceful and stabilizing nature.

Hestia’s commitment to the hearth was unwavering. When Poseidon and Apollo (her brother and nephew respectively) both sought her hand in marriage, she approached Zeus, king of the gods, and swore an oath to remain a virgin goddess, dedicating herself entirely to her sacred role. This choice set her apart as a figure of serene independence, unshaken by the passions and conflicts that so often embroiled the other gods. Her neutrality extended to pivotal moments in Greek mythology and the epic cycle, such as the Trojan War, where she alone refrained from taking sides.

Hestia’s presence was indispensable in both personal and communal rituals. Every sacrificial offering in the public or domestic space began and ended with an invocation to her, acknowledging her as the eternal flame that sustained Greek life. The “Homeric Hymn to Aphrodite” even notes that Aphrodite, goddess of love and sexual desire, had “no power over Hestia,” emphasizing her purity and resolve. Through her gentle yet powerful influence, Hestia embodied the values of stability, hospitality, and unity, and was revered for her role in maintaining familial and civic harmony – qualities that became vital during the colder months of the year.

The Hearth as the Heart of the Home

Imagine stepping into an ancient Greek home on a blustery winter’s evening. Outside, cold north winds sweep through the hills, but inside, the hearth’s fire glows warmly. Its flames dance on the stone walls, casting long shadows as the family gathers for a simple meal. The air is rich with the scent of burning olive wood and herbs like thyme and oregano, which were often added to the fire. Here, around the hearth, life unfolded.

The hearth was more than a practical necessity; it was a sacred space. It connected the mortal and divine, offering both physical warmth and spiritual reassurance. Families gathered around it to share food, tell stories, and perform rituals. Newborns were introduced to the family in a ceremony called the “amphidromia,” where they were carried around the hearth, symbolizing their acceptance into the household. Guests were welcomed with the lighting of the hearth’s flame, underscoring the sacred duty of hospitality (“philoxenia,” meaning “love of the foreigner”).

In winter, when agricultural work ground to a halt, the hearth became the focal point of domestic life. Ancient Greek homes were designed to make the most of this central feature. Typically built around a courtyard, these houses not only offered much-needed respite from the oppressive heat of summer but also provided insulation against the cold during winter. Constructed with thick stone walls and clay-tiled roofs, they maintained a balanced interior climate throughout the year. The hearth, located in the main living area, was often the sole source of heat in wintertime.

Feasting and storytelling were integral to these long winter evenings. Food was prepared over the hearth, often simple but nourishing: stews of lentils or chickpeas, freshly bread baked, dipped in olive oil or wine, and occasionally roasted meats. The act of sharing food and warmth reinforced bonds within the household, creating a sense of togetherness that helped them endure the harsh season.

Civic Hearths: The Sacred Flame of the Polis

Hestia’s influence extended beyond individual homes to the wider community. At the heart of every Greek city-state (“polis”) was the “prytaneion,” a public building that housed the city’s sacred hearth. Here, a holy fire dedicated to Hestia burned continuously, symbolizing the unity and stability of the community. This flame was more than a religious emblem; it represented the collective identity and endurance of the city.

In times of war or colonization, a flame from the prytaneion was carried to light the hearths of new settlements, maintaining a spiritual connection to the mother city. This practice highlighted Hestia’s role as a unifying force, ensuring that the bonds of community persisted even in the face of uncertainty and change.

The prytaneion also served as a venue for civic celebrations and feasts. In Olympia, for instance, the prytaneion stands to the north-west of the Temple of Hera, and hosted celebrations and feasts for victors of the Olympic Games. The sacred hearth within this building was a place of honor – the Altar of Hestia – where the original Olympic flame burned in homage to the goddess. In Athens, the exact location of the prytaneion remains uncertain. The second century AD Greek writer Pausanias suggested it was somewhere east of the northern cliff of the Acropolis, while other scholars argue it was located on the Acropolis itself. Regardless of its precise site, the prytaneion symbolized the heart of the city’s political and spiritual life, reinforcing the idea that Hestia’s flame sustained not just families but entire societies.

© Shutterstock

Winter Festivals and the Hearth’s Light

Winter in ancient Greece was a season of reflection, resilience, and renewal. Several festivals marked this time of year, blending themes of light and community that resonated with Hestia’s symbolism. Though Hestia herself had no specific winter festival, her presence was deeply felt during these celebrations.

The “Poseidonia” festival, celebrated around the midwinter solstice, was dedicated to Poseidon, god of the sea, earthquakes, and horses. Particularly popular in coastal regions like the Saronic island of Aegina, a once fierce naval rival of Athens, this festival sought Poseidon’s favor for safe maritime ventures and protection from the sea’s unpredictable forces. While historical details are sparse, Homer’s “Odyssey” (Book III) describes sacrifices and feasting on the shore of Pylos that brought communities together during this dark season.

Hestia’s hearth would have illuminated such gatherings, offering warmth and unity as participants honored Poseidon. The communal feasting, a hallmark of both Poseidonia and other winter festivals, closely aligns with Hestia’s role as the goddess of hospitality and shared sustenance. Her sacred flame symbolized the resilience and togetherness that allowed these ancient communities to endure and even celebrate in the heart of winter.

The Roman festival of Saturnalia, which had roots in Greek customs, also bears traces of Hestia’s influence. Held around the time of the midwinter solstice, from the 17th to 23rd December in the old Julian calendar, Saturnalia celebrated the warmth and unity of home, temporarily reversing social hierarchies to foster goodwill and generosity. Like our own Christmas celebrations, gifts were exchanged during the Saturnalia festival. The Roman poet Catullus (c. 84 – c. 54 BC) famously called it “the best of days.”

Click here to learn more about ancient Greece’s winter festivals.

Hestia’s Legacy in Modern Traditions

Though the worship of Hestia has been confined to history, her influence lives on in modern winter and Christmas traditions. The lighting of candles, the gathering of families around fireplaces and dining tables, sharing food, and the symbolic warmth of home all reflect her ancient role. In Greece, traditions like “kalanta” (caroling) and the baking of Vasilopita (New Year’s bread) preserve trace elements of her legacy, blending ancient customs with Christian practices.

Hestia’s hearth reminds us of the power of light and warmth to sustain us through dark times and the cold midwinter. For the ancient Greeks, her flame represented not just physical heat but the resilience of the human spirit. Today, as we gather around our own sources of warmth this Christmas and New Year – be it a roaring fire or the company of loved ones – we honor her enduring message: that even in the coldest seasons, there is a light within that unites and uplifts us.