Recipe: Eggs with Tomato – the Mykonian “Sun”

On Mykonos, this simple yet vibrant...

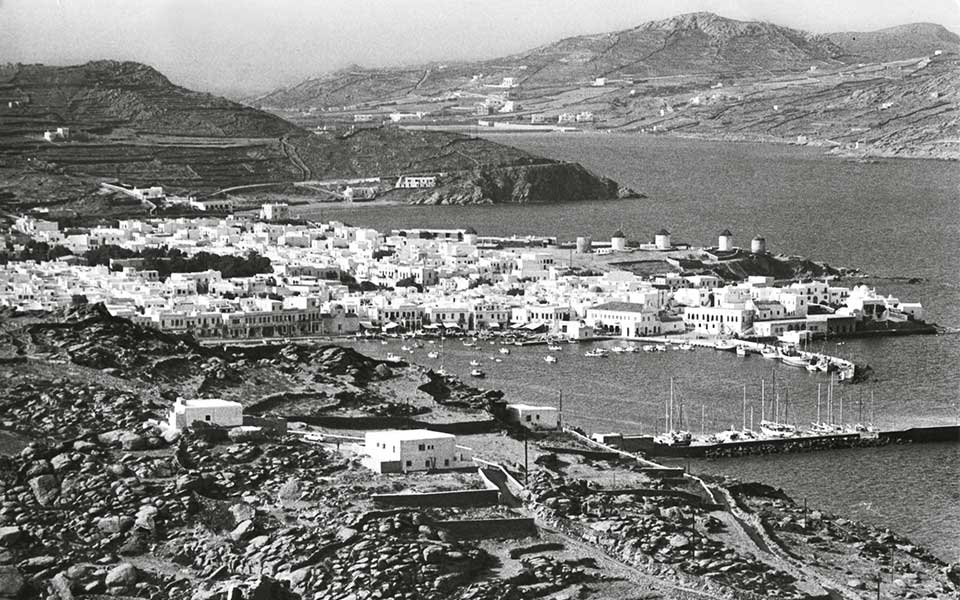

General view of Hora and Gialos from the hill of Dagous. Megali Ammos and Korfos are in the background (1970s).

© Archives of the Panayotis Kousathanas Library, Mykonos

Locals and outsiders, residents and visitors, we all bear a deep responsibility for the fate, good or bad, of this place. I should mention, first of all, the unbelievable changes that have occurred at Platy Gialos Beach. As a child, I often went there in the summer; it was where the “cottage” was, the rural farmhouse of Grandpa Panayiotis and Granny Anezo. And, of course, Platy Gialos isn’t the only place to have suffered such brutality. Other intrusions and modifications, just as great or even greater, to the island’s unique natural and architectural beauty can be found everywhere.

The same vista of Hora & Gialos today, after half a century of unbridled construction.

© Perikles Merakos

In order to comprehend the radical changes that mass tourism has brought in recent years, it suffices to look at the travel stories of summer visitors from the 1950s and 1960s. They all speak enthusiastically not only about the beauty of the place but also about the warmth and hospitality of its inhabitants. There, on the sands of Platy Gialos, and on other beaches, too, villagers generously treated the visitors of that period to whatever was on hand to give: a bunch of grapes and a few figs on a ceramic plate, a carafe of cool well-water to ease the summer heat. The locals would set these offerings down and then just disappear. “Good Lord, we don’t want the stranger to think we’re expecting to be paid!” It was gestures like these that slowly built up the so-called “tourist miracle,” tourism that was, in fact, neither a miracle from above nor a bolt from the blue. On the contrary, it was built slowly, patiently, and steadily on the island, beginning as far back as the 1920s.

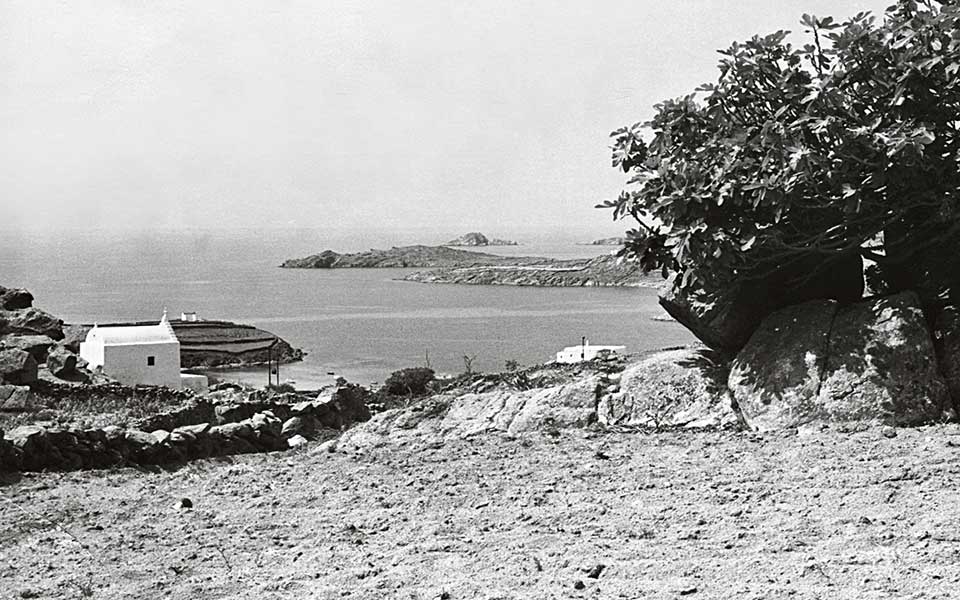

The church above Ornos. In the background are the Prasonisia islets (1970s).

© Archives of the Panayotis Kousathanas Library, Mykonos

On the left is the Cape of Ai Giorgis of Trachili, where large hotel complexes have been constructed and there is no public access to the sandy beach. To the right are the capes of Glyfadi and Aleomandra, which have also been built upon.

© Perikles Merakos

These days it’s difficult to find gestures like that; that ethos has been frayed beyond recognition. After all, who has the time or energy to be as tolerant and hospitable to such masses of people? Today’s tourism is much more than a small island can bear; this tiny little boat is so weighted down, it’s on the verge of capsizing. Even into the 1970s and 1980s, things on the island were still of human proportion; there were a few little tavernas, a handful of small unassuming hotels and some rooms to let, which served those who came to swim at shores free from the din of loud music and without lounge chairs sprouting from the sand or other silliness of that sort. How are beaches where 200 can sit comfortably supposed to bear 2,000 people stomping across them on a daily basis? Almost all of the island’s 45 beaches have been trampled, squeezed dry, fallen prey to the insatiable rapacity of everyone around. There are the recent, noteworthy cases of Panormos and Ftelia, but these sad stories have older precedents as well.

How did this happen? What supposedly responsible party signs a paper allowing the shoreline to be so shamelessly abused, permitting villas, hotels and restaurants to be built a half-meter from the waves, blocking access to the sea except for those willing to clamber over the rocks, or fight their way through the dense, untrimmed forest of lounge chairs and umbrellas that have sprouted on the beaches? Shame on whoever signed the papers that allowed boulders to be unearthed; granite hills to be flattened; enormous homes to be built on mountaintops; or ridiculously large structures thousands of square meters in size, as conspicuous as Roman villas, to be plopped down on just a few hectares of land, sometimes even less. Laws cease to truly exist when they aren’t enforced, when mechanisms for monitoring offenses and punishing offenders fail.

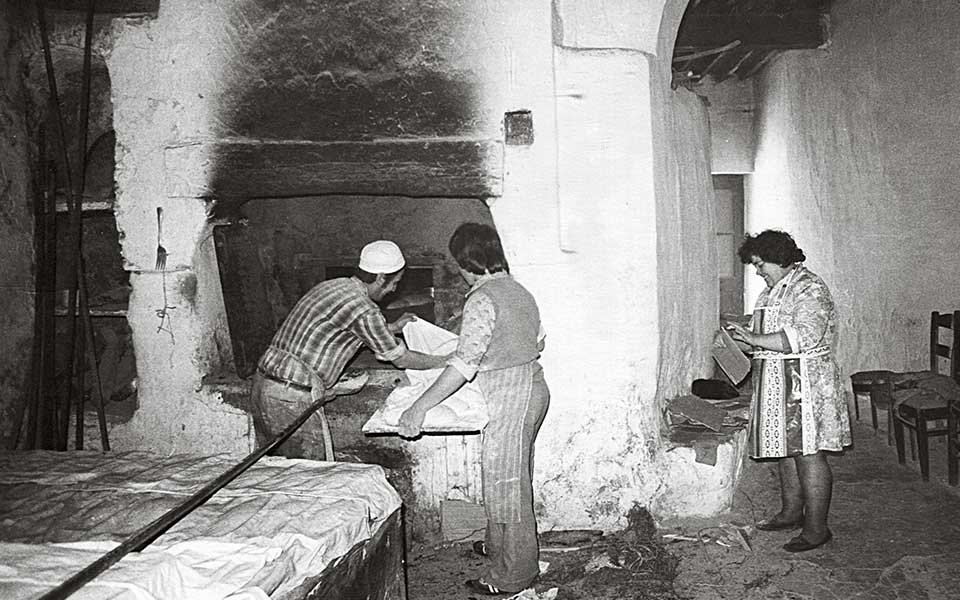

There are so few permanent residents in Hora today that some age-old services are no longer required. The old oven at the Gioras bakery, which produced bread for centuries, baked its last loaf last year.

© Archives of the Panayotis Kousathanas Library, Mykonos

Today, Gioras is a cafe and the oven is just a curiosity for customers dropping by for cake and coffee.

© Perikles Merakos

One shuddered to see what happened last winter to once-beautiful Psarou, whose beach is sister to Platy Gialos. Ancient gardens that had been home for centuries to fruit trees growing lemons, oranges, figs, carob beans, quince and greengage plums, as well as to grape arbors and other botanical treasures, were all uprooted and replaced by “exotic” plants, including coconut palms! The rocky ridges were flattened, the earth so thoroughly mined that the sea broke into the pit left by the excavations – nature taking its revenge – and all this just so what was once a paradise could be turned in an endless parking lot, an enormous pleasure dome. And to top it all off, in a move that would have made us laugh if it didn’t make us cry, even camels have been brought in on occasion, to serve as mounts for the pleasure and entertainment of wealthy foreigners and plenty of senseless Greeks, too!

The lure of profit has turned everything to dust, and people all over the island sport expressions of fateful apathy in the face of the island’s creeping disease. Every winter, cement mixers carry thousands of tons of cement, day and night, from one end of the island to the other. Every summer, an ever-larger army of rented and private vehicles – cars, mopeds, motorcycles, four-wheelers (technically forbidden), unlicensed passenger limousines and beater cars whose owners can’t afford their upkeep but still think of them as status symbols – barrel down the island’s narrow and dangerously unmaintained roads, terrifying the inhabitants and even causing fatalities. And what about Mykonos Town? We’ve forsaken the cool meltemi wind in favor of air conditioners; instead of the sun and the moon, we’ve chosen floodlights that blind people day and night. Passageways and stairs, little gardens and stone walls have all been knocked down so that shops and businesses can further overrun the place. And whatever charming little corners once remained are now full of tables and chairs: even the island’s churchyards and museum courtyards are littered with loungers, pillows and nargiles!

Marso’s house in Lakka has been converted into a restaurant and the well is used as a dining table.

© Archives of the Panayotis Kousathanas Library, Mykonos

© Perikles Merakos

This insatiable hunger for profit is everywhere. “Where will roads like this lead us?” the great poet George Seferis asked back in 1965. All of this excess and lack of measure is sure to lead the island into great suffering and misfortune. Once, when people truly felt deprivation, tourism was a blessing, because it eased the islanders’ difficult economic straits, a result of neglect by the state; it was a joy, and a fair reward, for them to see their lives and those of their children changing for the better. Yet who could have imagined that the island’s residents, locals and foreigners alike, would become so blinded by avarice as not to realize that they’ve long since exceeded the limits the island itself sets, thanks to its size and its character? The unconscionable pilfering of the island is leading to its forced self-destruction as, greedily and mercilessly, it is being made to devour its own flesh.

I offer this jumbled account of just a few of these disasters, in the hope of reaching the decent, respectable ears of some responsible party, if there are any left. And yet I can’t help but wonder how uncaring we have become, to make such a mess of the most beautiful place, a place we were lucky enough to call our own. The first contemporary hymns to this island can be found as early as 1925, in a letter by Nikos Kazantzakis, and soon after in 1933, in Giorgos Theotokas’s novel “Argo.” How many hidden strengths, how much resilient beauty must this island have had in order to have withstood almost a century of misuse and consumption, so much violence, stress, and distress? And how long will it continue? Similar examples from elsewhere, including from our own neighboring island of Delos, are incapable of serving as examples and of convincing us of the need to change course, even at this late date.

And thus both the sensitive native and the respectful immigrant from elsewhere who came to love the island as his home feel like Seferis’ exiled friend, who, returning to his homeland, comes face to face with something unrecognizable.

Marso’s house in Lakka has been converted into a restaurant and the well is used as a dining table.

PANAYÓTIS KOUSATHANÁS is a poet, writer and essayist. He was born in 1945 in Mykonos, where he lives. He studied English and Greek Literature at the University of Athens and worked for twenty years as a teacher in secondary education. He has published a total of thirty books. Awards and distinctions: Maria Per. Ralli Prize (1980), Greek State Prize for Chronicle-Testimony (2002), Greek State Prize for Short Story (2009). He was also awarded with the Mykonos Municipality Medal (2011) and the Athens Academy Medal (2014).

On Mykonos, this simple yet vibrant...

From Santorini sunsets to ancient ruins,...

Francesca Chanioti, a home cook from...

Discover Greece’s islands in September with...