The French Painter Who Found his Island Muse...

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

© Wolfgang Bernauer

Those residents of densely populated cities who happen to spend some time in a village during their vacation will enjoy, not only the beauty of nature and renewed contact with traditional ways, but a serenity and revitalization that their fast-paced city environments do not offer them.

Switzerland with its green, alpine villages would certainly seem to fit the stereotype as a source for such tranquility, but for the Swiss ophthalmologist and photographer Wolfgang Bernauer, the antidote to the hustle and bustle of urban existence was found here, among the villages of Greece.

© Wolfgang Bernauer

At an early age, Bernauer began exploring different aspects of photography through his father’s collection of old cameras. Over time, he also developed an interest in people who chose to live in remote areas.

In 1996, a stay of several weeks in the village of Olympos on the island of Karpathos provided the inspiration for a long-term project that has resulted in a volume of photographs called “My Greek Village,” published in 2019 by Bildperlen Publications.

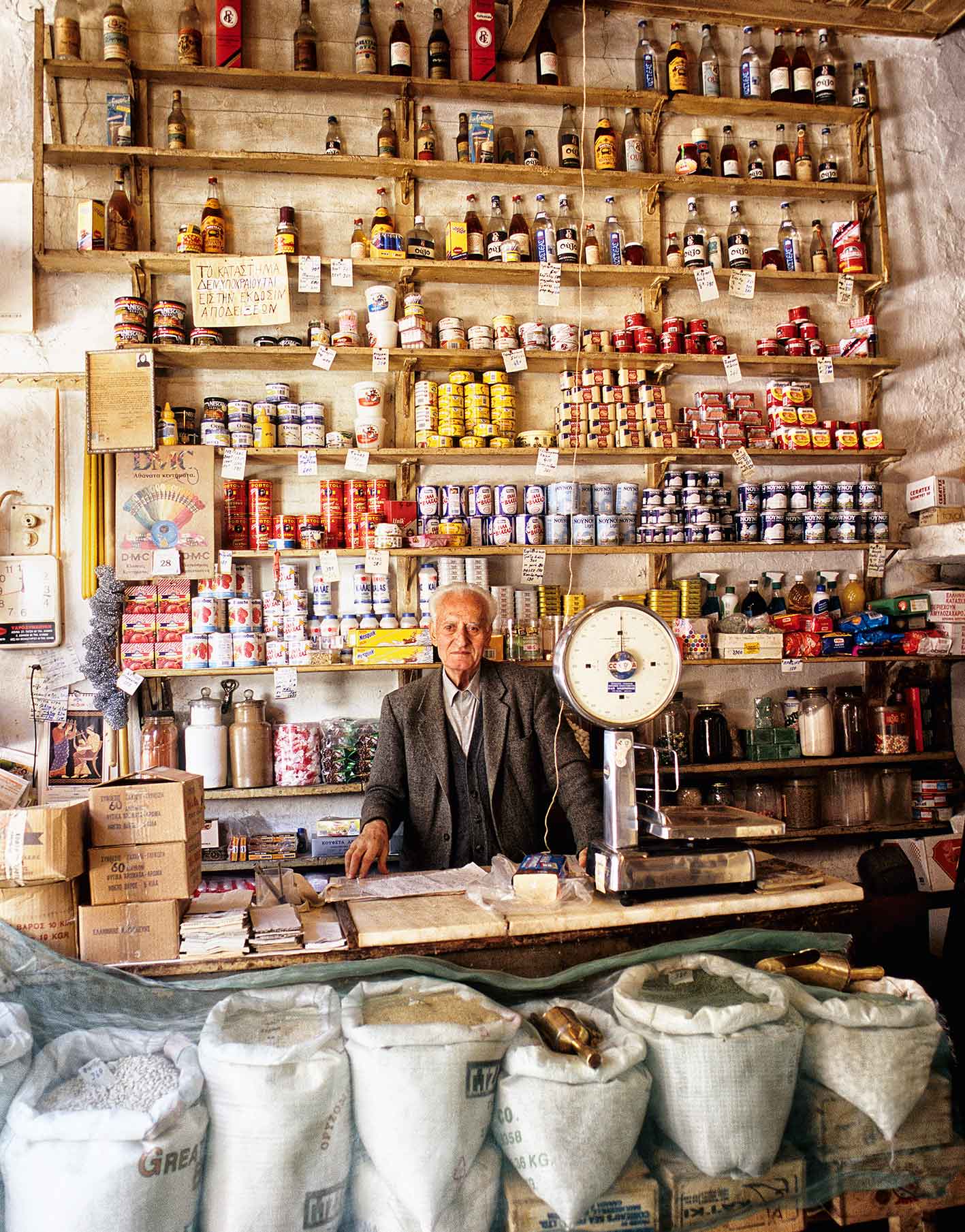

“At the very beginning,” Bernauer says, “the central theme was not that clearly defined. As I had always been interested in the cultural and social life of people living in remote or rural areas, I started to record their biographies, their traditional way of life, their housing, their rituals, and crafts. That was the beginning of the project: a collection of encounters with a vanishing world.”

© Wolfgang Bernauer

© Wolfgang Bernauer

Photos that he took of the rituals and traditions of Easter on Karpathos, where the women decorate the Epitaph with bunches of wildflowers and bake “avgoules,” traditional Easter cookies, were the start of a 5000-photograph collection. Choosing which of these photos would go into the book was done based on stringent criteria, the main one being that the photograph tell a story, under the watchful and dispassionate eye of photo designer Christian Beck.

“A single still picture can tell a whole story,” says Bernauer. “Viewing a still picture stimulates your imagination and your brain starts to complete the image. What about the smell, the noises, the temperature, the interactions, the emotions? In my opinion, photography is the most compact medium for delivering a whole story.”

© Wolfgang Bernauer

The research to find the authentic places and people that would serve Bernauer’s purpose was not an easy task. In addition to the internet, Bernauer perused a whole library of guidebooks, read articles in magazine, watched documentaries, interviewed locals, and took Greek lessons for years, all to capture with his lens the most remote areas of the country.

“The most difficult part,” Bernauer says, “was to find authentic places in Greece. An old workshop itself is – to my photographic eye – only a museum. A craftsperson alone may result in a nice portrait but does not tell a story. I am interested in the living traditions, in the interactions between the protagonists and their environment.”

© Wolfgang Bernauer

Bernauer says his shooting procedure is as follows: “Typically, there’s a friendly encounter, a coffee, a visit to the workshop or a small purchase. I ask for the chance to photograph the premises and I show some prints from previous encounters. I explore the lighting conditions and arrange an appointment for one of the next few days. People watch me as I work, and we have a conversation. At the end, I invite them to participate in the picture. Occasionally, I give some direction.”

© Wolfgang Bernauer

This idea of the village as an antidote to city living has meaning in Greece, in Switzerland and in every place where there are villages far enough from urban centers. Bernauer’s publisher, Martin Breutmann, noted as much when he suggested “The Village as a Metaphor” as a subtitle for the book. I asked Bernauer what kind of metaphor the Greek village could be, and whether he felt this might indeed apply to every remote area.

“’My Greek Village’ is a metaphor for an idealized place that embodies much of what we aspire to in life,” Bernauer says, “a place that makes us reflect on the most authentic values in life, because it doesn’t exist only in Greece. It is a place that exists everywhere, a place that must be protected. A place that, overall, exists in our hearts.”

Igor Borisov turned Kimolos into his...

While some historic buildings teeter on...

From fishermen’s chants to moonlit serenades,...

Where dusk, movement, and memory meet,...