Top 5 Archaeological Discoveries in Greece in 2024

From a mysterious Minoan structure to...

The iconic Navagio Beach wreck on Zakynthos, Greece's second most photographed site after the Acropolis of Athens.

© Unsplash

Greece is a country steeped in ancient history and mythology. It is also home to a rich maritime tapestry woven with tales of shipwrecks, both above and below the water. These wrecks, scattered across the azure Aegean and Ionian Seas, are not only archaeological treasures but also windows into Greece’s extraordinary maritime past.

You only have to look at a map of Greece and its myriad islands to appreciate the enormity of its coastline. In fact, according to the CIA World Factbook, Greece’s coastline is 13,676km long, the largest of any country in the Mediterranean Basin. And coupled with its lengthy history of seafaring, stretching back to at least the last Ice Age, 12,000 years ago, it’s a small wonder that its coasts and territorial waters are littered with wrecks and other sites of archaeological importance.

The wreck of Patris, a paddle steamer that ran aground off the island

While the most important and historically significant sites are still strictly off limits to all but a handful of highly qualified archaeological divers, guarded by strict laws concerning the protection of underwater cultural heritage, you don’t have to be a scuba diver to visit some of Greece’s most iconic shipwrecks.

In the following list, we’ve included several sites that sit proud of the waterline, beached in a dramatic coastal setting. Others lie over 100m below the surface, and remain the exclusive preserve of experienced technical divers. If you are a qualified scuba diver, click here for a list of underwater wreck sites that are currently accessible, including both historic ships and sunken aircraft.

It is also important to note that, while these shipwrecks provide invaluable insights into Greece’s maritime past, they also face ongoing threats from human activities, natural deterioration, and climate change. The delicate balance between satisfying the curiosity of tourists and preserving these underwater time capsules poses a significant challenge. Conservation efforts, such as site monitoring, controlled tourism, and the application of advanced archaeological techniques, are crucial to safeguarding these submerged treasures for future generations. If you do happen to visit any of the wrecks that are accessible to the public, be sure to look but don’t touch!

The Dokos shipwreck, situated near the island of Dokos (ancient name “Aperopia”) in the Argo-Saronic Gulf, adjacent Hydra, holds the esteemed title of being the world’s oldest known shipwreck. Dated to the Early Helladic II period, 2650-2200 BC, this remarkable archaeological find offers an unprecedented window into Aegean seafaring and trade in the Early Bronze Age.

Discovered in 1975 by pioneering underwater archaeologist Peter Throckmorton (1928-1990), at a depth of around 20m, the wooden remains of the hull have long perished. In its place, Throckmorton found a large cargo scatter, consisting of over 500 ceramic storage jars (amphoras) and other clay vessels, including cups, urns, and distinctive looking sauceboats; one of the largest collections of Early Helladic II pottery ever discovered. The site was extensively excavated between 1989 and 1992 by the Hellenic Institute of Maritime Archaeology (HIMA), using newly-developed underwater surveying equipment to record artifacts with pinpoint accuracy.

Based on the dating and scientific analysis of the ceramic vessels, the more than 4,000-year-old wreck is believed to have been a merchant ship, travelling between the coastal villages of the Gulf of Argos and the Myrtoan Sea. It likely sank sometime around 2200 BC. Stone anchors were also found on the seabed, some 40m from the main wreck site, as well as millstones (used for grinding cereal grains) and lead ingots.

Due to its importance as an archaeological site, the area around the Dokos wreck is strictly off limits to recreational divers.

Dubbed the “Parthenon of Shipwrecks,” the Peristera wreck is one of the most spectacular wrecks ever discovered. Located near the island of Alonissos in the Northern Sporades, lying at a depth of between 19 and 28m, the sites consists of an enormous mound of over 4,000 wine amphoras (two-handled ceramic storage jars) sitting proud of the seabed, indicating the original shape of the hull.

The wreck was first reported to the Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities in 1985 by a local fisherman. A team of archaeologists went on to survey and excavate the site through the 1990s, revealing an extensive cargo of tightly packed amphoras, as well as black-glazed bowls, two-handled drinking cups and plates, and elegant bronze tableware. Analysis of the artifacts indicate the ship, a large merchant vessel carrying a consignment of wine from the Macedonian port of Mende (Chalkidiki) and ancient Peparethos (Skopelos), sank sometime in the last quarter of the 5th century BC.

Only small fragments of the wooden hull were discovered during the excavations, buried under the massive weight of its cargo. Archaeologists estimate the ship to have been around 25-30m in length, and weighed over 120 metric tons when fully laden, dwarfing every other known wreck from the Classical period (5th and 4th centuries BC) in the eastern Mediterranean.

Protected by the National Marine Park of Alonnisos and Northern Sporades, the Peristera wreck was opened to the public as an underwater museum in August 2020, the first of its kind in Greece. The site is accessible to Advanced Open Water-certified divers or equivalent (qualified to dive to 30m), and is equipped with underwater signposts that provide information on the exhibits and their historical context.

Click here for our comprehensive guide to diving on the site.

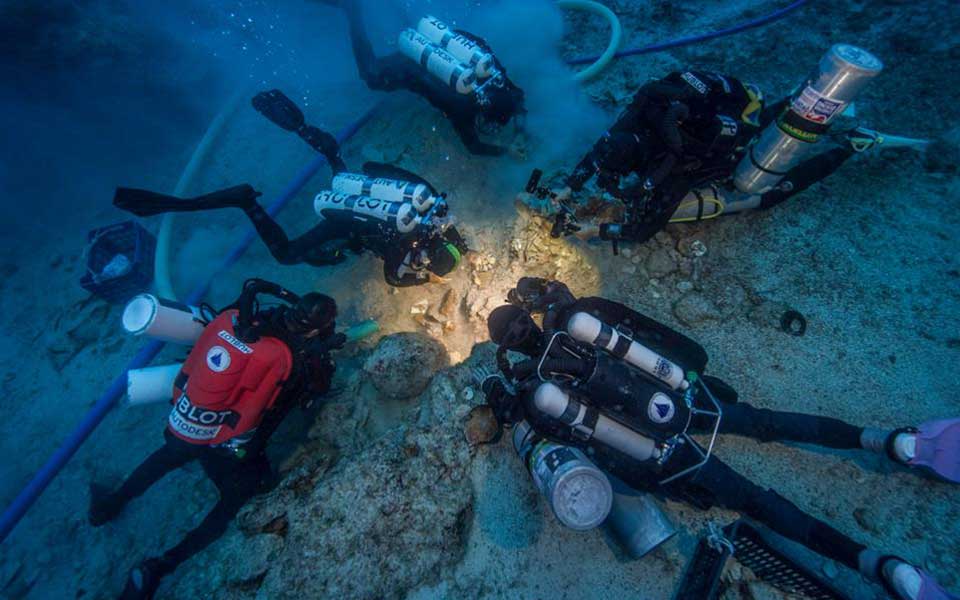

Archaeological divers working on the site of the Antikythera wreck in 2016.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

The Antikythera wreck, discovered in 1900 by a team of sponge divers off the island of Antikythera, is without doubt Greece’s most iconic shipwreck. Dated to the first half of the 1st century AD, this Roman-era wreck yielded a treasure trove of ancient artworks, including fabulous marble and bronze statues, and the mysterious Antikythera Mechanism, an intricate and sophisticated mechanical device often referred to as the world’s first analog computer.

A deepwater site, between 45-60m, only fragmentary remains of the wooden hull were found in-situ. Instead, a large scatter field of heavily concreted artifacts was found strewn across the seabed. Subsequent investigations of the wreck by Jacques-Yves Cousteau in 1953 and again in 1976, as well as more recent projects by Greek and international research groups, have recovered hundreds of priceless artifacts, including glassware, pottery, bronze statuettes, coins, gold jewelry, and even human remains.

A new 5-year project, launched by the University of Geneva in 2021, is using the latest advances in underwater survey technology to investigate the site and its surrounding area, in the hope of finding more pieces related to the Antikythera Mechanism.

Due to its immense historical importance, the Antikythera shipwreck is strictly off limits to all recreational divers. However, visitors to Athens can head to the National Archaeological Museum and see many of the artifacts recovered from the wreck on display in the galleries, including the famous Mechanism.

Click here for more information about the enigmatic Antikythera Mechanism.

he Mentor sank in a storm in September 1802, sending 17 crates of antiquities to the bottom of the Mediterranean.

© Hellenic Ministry of Culture and Sports / Ephorate of Underwater Antiquities

Lying off the southeast coast of Kythera, the wreck of the Mentor is linked to a highly controversial event that took place at the turn of the 19th century. The Mentor, a brig under British ownership, met its fate in a storm in September 1802 while transporting precious artifacts looted from the Parthenon by Thomas Bruce, 7th Earl of Elgin. The ship, bound for England with 12 passengers and crew, encountered stormy weather and crashed into the rugged coastline of Kythera, sinking to a depth of 23m.

The Mentor’s cargo 17 crates of marbles and sculptures from the Acropolis, including 14 pieces of the Parthenon’s frieze, was scattered across the seabed. Upon hearing news of the disaster, Elgin, who was not on the Mentor at the time, scrambled to salvage the crates of antiquities by hiring a team of sponge divers. Once the marbles were recovered, Elgin had them shipped on to Malta, and then to England, where, in 1816, he sold the collection to the British Museum in London.

The site, now a protected underwater archaeological zone, is the focus of ongoing investigations by Greece’s Ministry of Culture. The artifacts recovered from the Mentor, as well as large sections of its preserved wooden hull, continue to contribute to discussions on heritage preservation, underwater archaeology, and the complex legacy of Lord Elgin’s controversial actions in the early 19th century.

Click here for more information on the latest season of work on the Mentor.

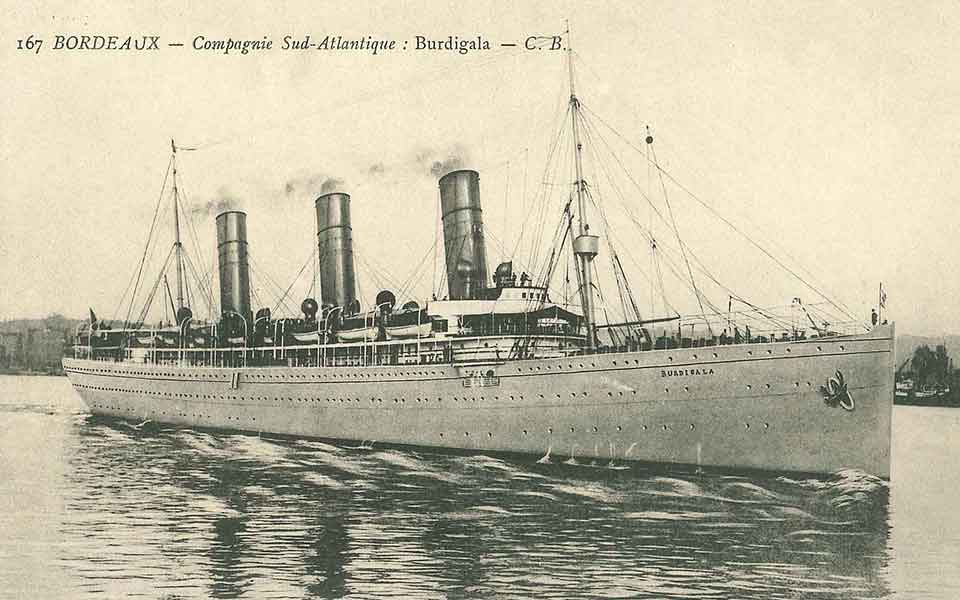

SS Burdigala

© Public domain

Resting off the coast of Kea in the Aegean Sea, the wreck of the SS Burdigala is a poignant reminder of the perils of wartime seafaring. Built for a German shipping line as the “Kaiser Friedrich” in 1898, it was later sold to the French Compagnie de Navigation Sud-Atlantique for use as a luxurious transatlantic liner. Renamed the SS Burdigala, it serviced connections between its home port of Bordeaux and destinations in South America.

Immediately after the outbreak of World War I, the veteran passenger ship was commandeered for service, initially as a troop transport, ferrying allied forces to the Dardanelles in the eastern Mediterranean, and later as an auxiliary cruiser, equipped with heavy cannons. During this period, the French government used every available vessel to support the war effort.

On November 13, 1916, having dropped off a shipment of men and equipment at the northern Greek port of Thessaloniki, the SS Burdigala embarked for its home voyage to Toulon, on the south coast of France. The next day, at 10:45am, approximately two nautical miles (3.7km) off the southwest coast of Kea island, the ship struck a mine, laid by a German submarine. The captain gave the order to abandon ship and, 15 minutes later, the giant vessel sank beneath the waves, with the loss of one life. Miraculously, the rest of the crew were able to safely escape the doomed ship and be picked up by a passing British destroyer, HMS Rattlesnake.

Now lying at a depth of approximately 60m, the wreck of the SS Burdigala is a challenging but rewarding site for experienced technical divers. The ship’s hull, which is split in two, lies upright on the seabed, the bow and stern sections separated by a large debris field, creating a haunting underwater tableau.

The Britannic, sister ship of the Titanic, served as a hospital ship during WWI.

© Public domain

The HMHS Britannic, sister ship to the infamous Titanic, met the same tragic fate as the SS Burdigala precisely one week later, off the opposite coast of Kea. Initially designed as a luxurious ocean liner, the Britannic was repurposed as a hospital ship by the British Admiralty to aid the war effort. In November 1916, a mere four years after the Titanic disaster, and one week after the sinking of the French SS Burdigala, the Britannic also struck a mine laid by a German submarine. At the time, she was the largest hospital ship in the world.

The explosion, occurring in the Kea Channel, between the island and Cape Sounion on the mainland, resulted in catastrophic damage to the ship’s hull. However, unlike its sister ship the Titanic, improved safety measures and the crew’s swift response resulted in the majority of 1,066 passengers and crew surviving, with the loss of 30 lives.

Today, the Britannic rests at a depth of around 120m, making it an enticing but challenging site for technical divers. Lying on its starboard side, the giant liner is surrounded by a debris field, including three of the four funnels, as well as piles of coal from the boiler room. As a designated war memorial, access to the wreck is restricted. Due to the challenging nature of the dive, several technical divers have sadly died while exploring the site.

The HMHS Britannic remains the world’s largest sunken passenger ship.

For more information on the sinking of the HMHS Britannic, click here.

The Olympia shipwreck, Amorgos

© Shutterstock

This next wreck features in a number of scenes in Luc Besson’s 1988 award-winning film, “Le Grand Bleu” (The Big Blue), a fictionalized story about the French free diver Jacques Mayol (1927-2001). The wreck of the Olympia, a Greek cargo ship that ran aground during a violent storm in February 1980, is set in the beautiful surrounds on Liverio Bay, on the coast of Amorgos, the easternmost island in the Cyclades.

Only the midship section of the vessel lies partially submerged. The rest, including the bridge, the aft deck, and the machinery on the bow section, sit proud of the surface and remain largely intact.

The vessel met its demise during a storm, as the captain sought shelter near the coast from strong northerly winds. The rough sea had other ideas, and threw the ship into the shallow bay. Thankfully, all the crew were rescued.

It is possible to reach the wreck site from the nearby sandy beach of Kalotaritissa, on the south coast of the island. Over the years, the Olympia has become a popular tourist attraction, and you don’t need to be a qualified scuba diver to see it!

The famous Navagio Beach wreck, the MV Panagiotis.

© Shutterstock

One of Greece’s most infamous shipwrecks is the MV Panagiotis, better known as the Navagio Beach wreck. Nestled on the pristine shores of Zakynthos, in the Ionian Sea, this shipwreck is a paradoxical blend of tragedy and beauty. In October 1980, the Panagiotis, a freighter carrying contraband cigarettes, ran aground during stormy weather while evading pursuit by the Greek navy. The vessel, now a skeletal remnant, lies half-buried in the sands of Navagio Beach, its rusty frame juxtaposed against the turquoise waters and towering white limestone cliffs.

Today, the iconic wreck and its stunning backdrop, routinely touted in travel magazines as Greece’s second most photographed site (after the Acropolis), can only be accessed by boat. Until recently, charter tours were available, but a dangerous landslide in September last year, preceded by an 5.4 magnitude earthquake, has forced local authorities to close Navagio Beach until further notice. Let’s hope that the necessary protection measures can be put in place soon.

In the meantime, you can still view the shipwreck from the limestone cliffs above the beach, offering panoramic views of the surrounding seascape.

The Dimitrios wrecked in mysterious circumstances on the coast of the Mani Peninsula in 1981.

© Public domain

The wreck of the Dimitrios, nestled along the rugged coastline of the Mani Peninsula, presents a haunting yet picturesque maritime relic. This abandoned cargo ship, believed to be a smuggling vessel, met its mysterious fate in November 1981, grounding itself on sandy Valtaki Beach, near the coastal town of Gythio. The ship’s weathered remains, with its rusted structure and peeling paint, create a surreal tableau against the rugged coastline.

The Dimitrios has become a captivating subject for photographers and a destination for curious travelers exploring the wild beauty of the Mani Peninsula. The vessel’s gradual decay, battered by the elements over the years, adds an eerie charm to the scene. The shipwreck has also acquired a sense of folklore, with locals and visitors speculating about the circumstances leading to its abandonment.

What is known about the Dimitrios is that is was built in Denmark in 1950 and later registered at Piraeus, the port of Athens. Many believe the small cargo ship was used to smuggle contraband cigarettes between Turkey and Italy. Whatever the circumstances surrounding its sinking, no attempt have been made to recover the ship since its abandonment. Visitors today can walk around and explore its rusting hulk from the beach.

From a mysterious Minoan structure to...

From ancient shipwrecks to treasures of...

How the cargo of a prehistoric...

Lost to earthquakes, swallowed by the...