‘Christmas will find me drinking ouzo, probably, instead of egg nog’

“He definitely wanted to see Greece.”

This line, from Patricia Highsmith’s The Talented Mr. Ripley, refers to the eponymous protagonist of that famed 1955 novel, who flirts with the idea of a trip to Greece for nearly the whole length of the book. The phrase could have, however, just as well have been about the author herself.

In his 2003 biography “Beautiful Shadow: A Life of Patricia Highsmith,” Andrew Wilson states that “her initial impulse to travel to the Continent probably stemmed from her reading,” and then supports this by quoting her good friend G. K. Kingsley:

“‘…nearly all her literary interests were embedded in the works of what the politically correct today characterize as dead white European males. One also should not discount the change of scene, recharging her batteries and the appetite for adventure, the opportunity to experience something completely different.’”

Highsmith traveled for the first time to Europe in 1949, buying tickets on the RMS Queen Mary with money she’d earned as a writer for comic books, and visited London, Paris, Naples and Positano, the last of which she later used as inspiration for the picturesque fictional port of Mongibello in The Talented Mr. Ripley.

She would return to Europe as an up-and-coming writer in 1951, and spend the next two years wandering around those places that would later serve as settings in her books. Highsmith stopped in Rome, Naples, Cannes, Barcelona and Trieste but, strangely enough, not Greece, in a near-parallel to the first travels of her character Tom Ripley who, although he has thoughts of Greece throughout the course of this novel, the first of five books featuring Ripley, only manages to reach the country at the very end of the story.

“He tried to turn his thoughts to Greece. For him, Greece was gilded, with the gold of warriors’ armour and with its own famous sunlight. He saw stone statues with calm, strong faces, like the women on the porch of the Erechtheum.”

At the novel’s end, Ripley will reach his gilded destination.

“He had decided in Venice to make his voyage to Greece an heroic one. He would see the islands, swimming for the first time into his view, as a living, breathing, courageous individual – not as a cringing little nobody from Boston. If he sailed right into the arms of the police in Piraeus, he would at least have known the days just before, standing in the wind at the prow of a ship, crossing the wine-dark sea like Jason or Ulysses returning.”

Upon landfall in Piraeus and fearing imminent arrest for either murder, forgery or both, Ripley will first found out that he is not a murder suspect and then, after taking a cab to the American Express offices at Syntagma, discover that not only is he safe from criminal charges but that he’s also soon to be rich; the inheritance for which he had committed murder would soon be his. Returning to his waiting cab, he tells the driver: “To a hotel, please, Il meglio albergo. Il meglio, il meglio!”

It’s likely that Tom Ripley’s second cab ride was a very short one, and that he ended up at the Hotel Grande Bretagne. After all, in Highsmith’s 1964 novel The Two Faces of January, her protagonist Chester MacFarland describes that establishment as “unquestionably the biggest and best hotel in Athens,” although chooses to stay at a hotel across the way in an effort to keep a lower profile.

“A few minutes later they were comfortably installed in a large, warm room with a view of the white, geranium-garnished balconies of the Grande Bretagne and of a busy avenue six storeys down, which Chester identified on his map of Athens as Venizelos Street.”

By the time she wrote this story, Highsmith had a good firsthand knowledge of Greece. She had come to Athens in December of 1959, had rung in the New Year in Nafplio, and had even visited Crete. By February of 1960, back in Manhattan, Highsmith was wondering how to use her memories of her trip in a book. She writes about it in her work “Plotting and Writing Suspense Fiction,” published in 1983:

“I remembered a musty old hotel I had stopped at in Athens, where the service was not very good, where the carpets were worn out, in whose corridors one heard a dozen different languages a day, and I wanted to use this hotel in my book. I wanted also to use the labyrinthian Palace of Knossos, which I had visited…While on this trip, I had been slightly rooked by a middle-aged man, a graduate of one of America’s most esteemed universities. His highly aristocratic but weak face could be the face of my con man, Chester Macfarland, in ‘The Two Faces of January.’”

It is in that book that Highsmith gives us detailed descriptions of Athens and of Crete. Chester Macfarland and his wife twice visit the Acropolis, take in Sounio at sunset, see the museums and watch a play, even though they couldn’t follow what was happening.

“After a few days in Greece, Chester found that he breathed more easily. He enjoyed the strange meals at tavernas, the little oily dishes of this and that, washed down with ouzo or a bottle of wine that usually neither of them liked, though Chester always finished it.”

© Perikles Merakos

Naturally, since this is a Highsmith novel, the quiet state of affairs doesn’t last, and as the reader follows the suspenseful unfolding of the plot, things turn darker and more complicated. From highly respectable Syntagma Square, the story heads to the little lanes of Plaka, the fringes of working-class Omonia, and the dark alleys of the city. Now the hotels are shabby and, once they leave the city, the misty winter landscape of the Greek countryside is bleak. The climax of the story takes place, of course, in the labyrinthine Minoan ruins of Knossos.

As her biographer Wilson notes, “Highsmith often drew inspiration from her surroundings, jotting down details about cities and countries in her cahiers under the special heading of ‘Places’; journeying to foreign countries, she said when still a teenager, was surely the ‘most desirable thing on earth.’ ”

This insatiable thirst for travel and for adventure brings to mind Rydal Keener, the young American who becomes entangled with the MacFarlands. Early in the novel, Rydal plays a game he calls “Adventure” that has as its aim an encounter with “The Right Person.” He imagines that he’d immediately know:

“Something would take place when his eyes met the eyes of the Right Person, there would be a shock of recognition, one of them would speak, they would have some kind of Adventure together…”

The discerning eye of Highsmith was particularly gifted at spotting the Right Person, who has always been none other than her reader, and indeed there is a shock of recognition, at least on the reader’s part, and plenty of adventure always follows.

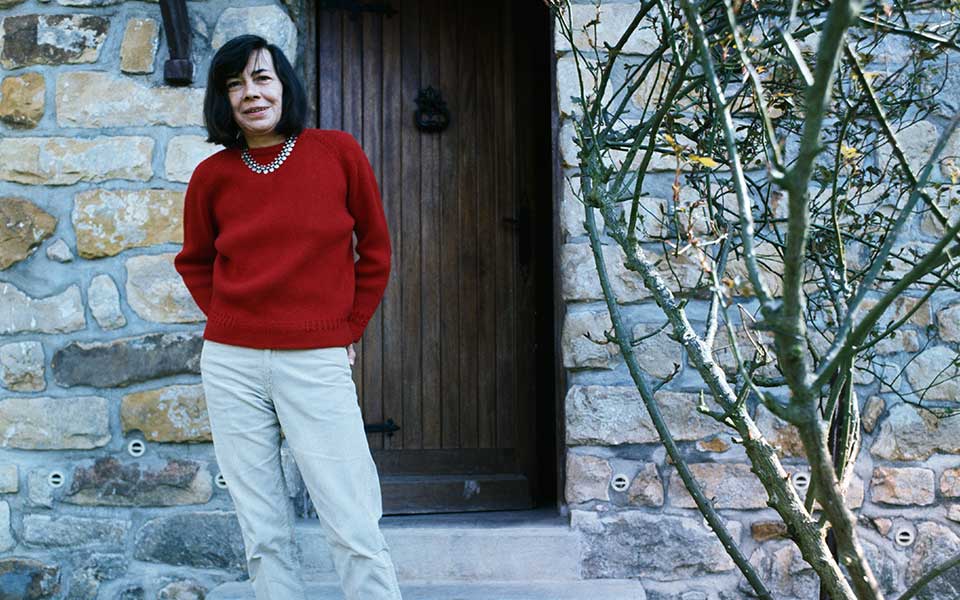

Patricia Highsmith is one of the most intriguing and unusual writers who ever worked in the genre of crime fiction, a genre that is full of fascinating types. A Texan who lived half her life in Europe, a lesbian with a strong misogynist streak, and a writer of crime stories whose core influences included Dostoyevsky, Flaubert and Sartre, Highsmith was a complex character.

Her friend Graham Greene dubbed her “the poet of apprehension rather than fear,” while others who knew her chose other words to describe her: cruel, depressed, cynical, rough, plainspoken, dryly funny, hostile, misanthropic, great fun to be around, mean, unlovable, unloving, encouraging, very sweet, amoral.

Her protagonists are in search of identity and in transition, both existentially and literally, as they change passports, names and personalities. They are travelers, exiles, something between immigrants and tourists, refugees without a cause.

As for Highsmith herself, if it were necessary to choose just one image of her to sum her up, I’d go with this: she’s at a London cocktail party in 1966, and in her enormous Mexican handbag there’s a flask of scotch and a giant head of lettuce, crawling with about a hundred small snails. In those days, she took the snails with her everywhere.

However, even without images, her books are more than enough to bring her to us, allowing us to seek her out within her own words:

“It is then good to remember that artists have existed and persisted, like the snail and the coelacanth and other unchanging forms of organic life, since long before governments were dreamed of.”