“Was I really going to get on a plane and fly all the way to Greece? The answer was yes. I had no other choice.”*

A small-framed, bare-chested Japanese man lets water from the hose of the remote gas station run down his back. Sweat-covered and burnt by the relentless sun, he tries to regain his breath in order to answer the man who is looking at him questioningly:

“When the old man at the gas station hears what I’ve done, he snips off some flowers from a potted plant and presents me with a bouquet. You did a good job, he smiles. Congratulations.”**

A short while later at the village café, he will finally enjoy the ice-cold Amstel beer that he has been dreaming about for the past 4 hours. He is the novelist Haruki Murakami and “what he’s done” is to run, alone, the legendary distance of 42.2 km that separates Marathon and Athens.

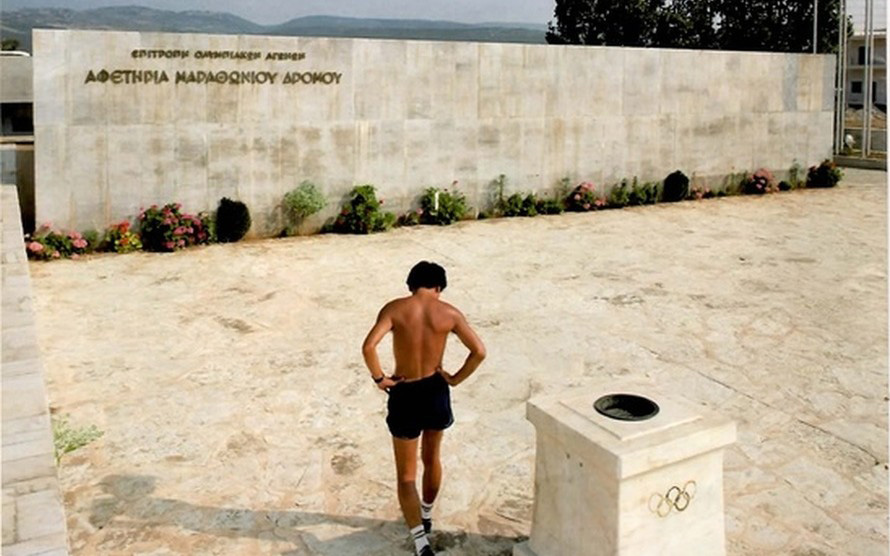

He came to Athens in July of 1983, in order to write a travel article. And with the enthusiasm brought by a newly discovered love of running, he decided to run the classic Marathon route. By himself and “backwards” – beginning, that is, at the Panathenaic Stadium and ending in Marathon – in order to avoid the traffic in the center of Athens and the heat.

“Even dogs just lie down in the shade and don’t move a muscle. You have to watch them for a long time before you can figure out whether they’re still alive. That’s how hot it is. Running twenty-six miles in heat like that is nothing short of an act of madness (…)When I told Greeks my plan to run alone from Athens to Marathon, they all said the same thing: “That’s insane. No one in their right mind would ever think of it.” **

Even in the face of the adverse conditions, Murakami would reach his goal.

“The run from Athens to Marathon took me three hours and fifty-one minutes. Not exactly a great time, but at least I was able to run the whole course by myself, my only companions the awful traffic, the unimaginable heat, and my terrible thirst. I guess I should be proud of what I did, but right now I don’t care. What makes me happy right now is knowing that I don’t have to run another step. Whew!—I don’t have to run anymore.”**

Despite the hardship, Murakami would abandon neither running (he has since completed over 30 marathons), nor Greece. In 1986, following the publication of his novel Hard-Boiled Wonderland and The End of the World – and in a move reminiscent of his protagonists – he would disappear from Japan seeking a utopia of serenity and quiet in Italy and Greece.

In Uten Enten (Days of Rain, Days of Fire), a book of travel reminiscences, he describes an event-filled visit to the monastic state of Mt Athos. At the end of the trip:

“…he breathes a sigh of relief to be back in a normal town where he can have a beer and listen to the Beach Boys, [but] what he most recalls are the words of a monk inviting him to convert to Greek Orthodoxy and come live in a monastery. Murakami laughs off the suggestion of becoming a believer, but concludes that, ‘If you search the world you ‘ll probably never find a place of such depth and conviction as the mountains of Athos’… Which of the two, he muses in the final lines, is the ‘real world’, that of the sacred mountain, or the world outside?” ***

Between 1986 and 1989 he would live in Italy and Greece, writing the novels that would establish him as one of the world’s great writers, Norwegian Wood and Dance, Dance, Dance.

A decade later, in Sputnik Sweetheart, he would revisit Greece. In his writing, we once again encounter the relentless heat:

“The sky was cloudless, not a hint of rain. The sun baked the stone walls of the houses. A layer of dust covered the gnarled trees beside the road, and people sat in the shade of the trees, or under open tents and gazed, almost silently, at the world. I began to wonder if I was in the right place. The gaudy signs in Greek, however, advertising cigarettes and ouzo and overflowing the road from the airport into town, told me that—sure enough—this was Greece.”*

We also once again encounter the kindness of strangers:

“A wrinkled old man sitting next to me offered me a cigarette. Thank you, I smiled, waving my hand, but I don’t smoke. He proffered a stick of spearmint gum instead. I took it gratefully, and continued to gaze out to sea as I chewed.”*

As he chews his gum, K., the protagonist of the book reaches a small island in the Dodecanese which closely resembles Symi. He futilely attempts to investigate the disappearance of the woman with whom he has fallen hopelessly in love.

Eating fish off the grill, swimming in azure waters, passing goats on rocky hillsides and greeting islanders riding donkeys, Murakami succeeds in his writing in capturing the Greek summer unencumbered by touristic clichés, not because he avoids them but – rather the opposite – because he is not afraid of them.

He “inhales” Mediterranean stereotypes, like his protagonist does the sea breeze:

“The kind of air that felt like if you breathed it in, your lungs would be dyed the same shade of blue.”*

And he turns them into stories that share the emotional intelligence of lyrics by the Beatles:

“It wasn’t until the nineteen-eighties, when I was living on an island in Greece, that I went down to the beach and listened to the White Album from start to finish on my Walkman. I listened to it over and over and was blown away by their music for the first time.”****

A not inconsiderable debt to the Greek sunshine.