Discovering Archaeology in the Athens Metro

Beneath the busy streets of modern...

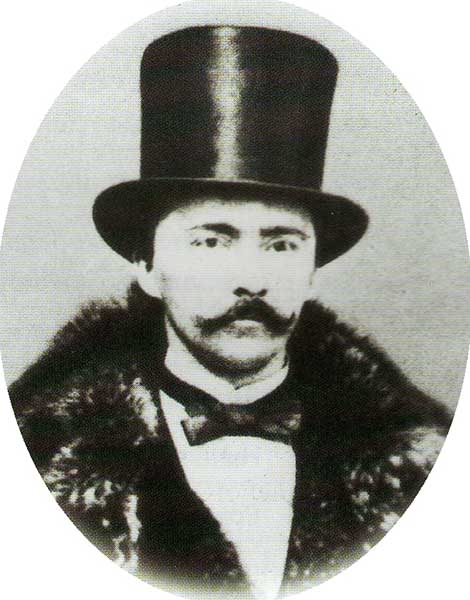

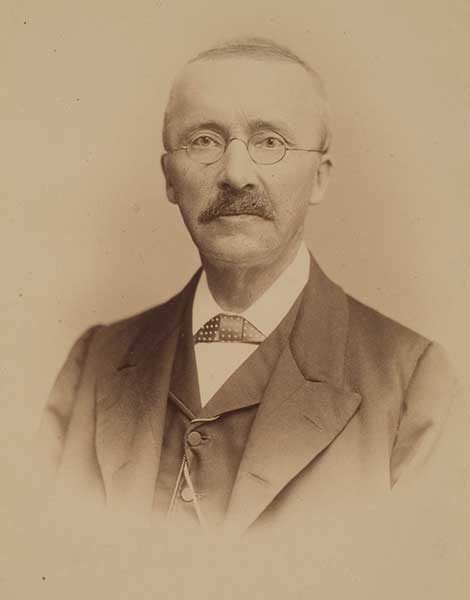

1869 engraving of Heinrich Schliemann, best known as the discoverer of the ruins of the legendary city of Troy.

Blessed with luck, raw determination and an extraordinary aptitude for the study of foreign languages, Heinrich Schliemann was a complex character – part dreamer, part mad genius. Dismissed as a fraud by many of his contemporaries, including scholars who strongly criticised his “savage and brutal” excavation methods, he nevertheless made some of the most important discoveries in the early history of Greek archaeology.

With a dog-eared copy of Homer’s Iliad in one hand and a pickaxe in the other, his heavy-handed yet audacious search for the legendary city of Troy in northwest Turkey married the worlds of mythology and archaeology, and, for the first time, paved the way for the systematic study of the Bronze Age Aegean. His subsequent investigations in Greece, notably at the major centers of Mycenae, Tiryns and Orchomenos, did much to shape the discipline in the late 19th century and beyond.

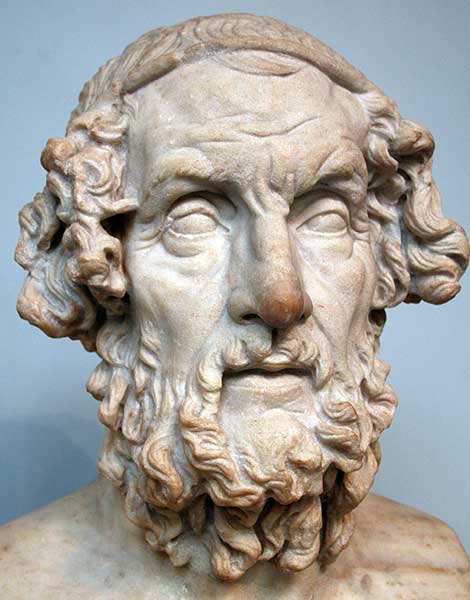

Marble bust of Homer. Roman copy of a lost Hellenistic original of the 2nd c. BC (British Museum, London).

Schliemann as a young man

Schliemann was born on January 6, 1822, at Neubukow, a small town in the Grand Duchy of Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania, northern Germany. Raised alongside eight siblings, he was the son of a poor Lutheran pastor who schooled him in the Iliad and the Odyssey from an early age, sparking a passion for Homer and ancient Greece that would last a lifetime.

Denied a formal university education due to his father’s poverty, the young Schliemann started his working life as an apprentice at a grocery in Fürstenberg, before becoming a merchant’s clerk in the northern port city of Hamburg.

In 1841, his planned emigration to South America in search of better, more lucrative employment opportunities ended in disaster when the ship sank off the nearby Dutch coast. Washed ashore, he was taken in by a local family and nursed back to health, moving to Amsterdam determined to try his luck.

Following a series of menial jobs, he became a book-keeper for the trading house B.H. Schröder and Co., and soon discovered he had a preternatural ability for foreign languages. Within a year, he had taught himself to speak not only Dutch, but also Spanish, Italian and Portuguese, to be complemented by Russian later on.

During his lifetime, Schliemann expanded his knowledge to include English, French, Swedish, Danish, Polish, Greek, Latin, Arabic, and Turkish, besides his native German – an extraordinary feat that consisted of reading aloud, working with native speakers, and copious amounts of rote learning.

Shipwreck off a Rocky Coast, by Wijnand Nuijen, c. 1837, Dutch painting, oil on canvas.

© Everett Collection / Shutterstock

In 1846, after mastering Russian, B.H. Schröder and Co. sent him to St. Petersburg to serve as a commodities trading agent. His prodigious knowledge of languages enabled him to become a much sort-after representative in the import-export business. A year later, at the age of 25, Schliemann set up his own commercial trading firm, engaging in a number of highly successful business ventures that accrued him a great wealth.

Following the unexpected death of his brother Ludwig in California, he traveled to America in 1850 and began a series of business activities in the gold rush, further boosting his own personal fortune, albeit in controversial circumstances. On his return to Russia, he profiteered from the Crimean War (1853-1856) by selling vital materials for the manufacture of armaments to the Russian government.

By 1858, at the age of 36, he was wealthy enough to retire and embark on his life’s passion: the pursuit of the legendary city of Troy, as described in the pages of Homer’s Iliad.

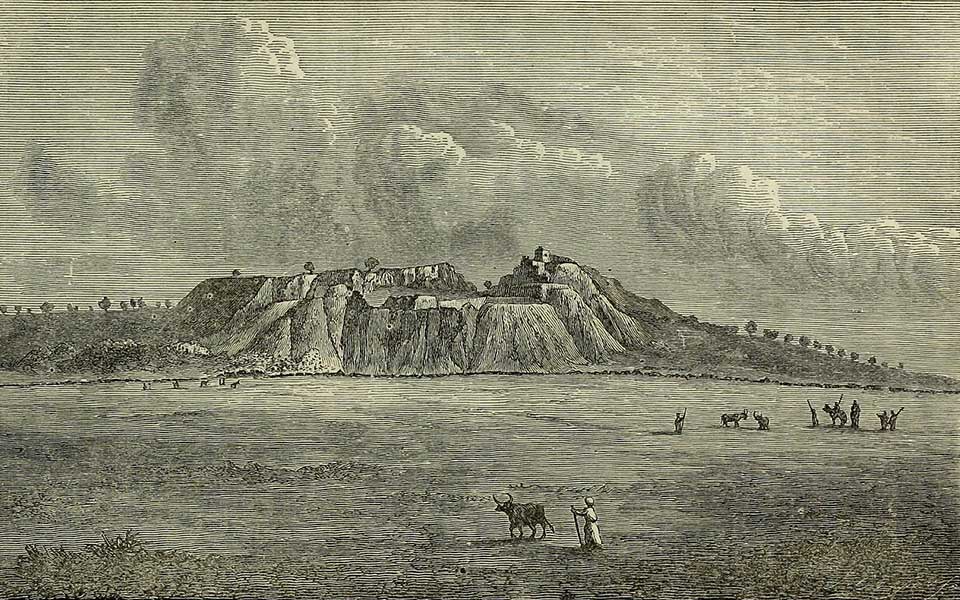

Hissarlik, pictured in 1880. The notch at the top is "Schliemann's Trench."

Despite his lack of formal training in archaeology, a field still in its infancy, Schliemann nevertheless made steps towards the study of ancient Greece by enrolling in language, literature and philosophy courses at the prestigious Sorbonne in Paris.

In 1868, he went on a prospecting trip to the Greek island of Ithaca in search of the palace of Odysseus. From there, he traveled to the Marmaris Sea to make his way inland and start the quest for Troy. During his entire journey, an old copy of the Iliad was Schliemann’s one and only true companion, the one book he considered his indispensable guide to discovering Troy.

On August 9, 1868, Schliemann conducted test excavations at Pınarbaşı, a hilltop at the southern end of the Trojan Plain, widely believed to be the location of the ancient citadel. Nevertheless, his soundings revealed bedrock at a level of one meter, quickly ruling it out.

On the 13th, he switched focus to a high plateau at Hissarlik, covered with broken pottery and fragments of worked marble; a site that had been previously excavated by amateur archaeologist and local expert Frank Calvert. During a surface survey of the plateau, Schliemann, along with five labourers, successfully located the remains of four solitary and half-buried columns, indicating the site of a large temple.

In his book, Ithaka, der Peloponnesus und Troja, published in 1869 – for which he was awarded a PhD in absentia by the University of Rostock – he writes:

“After having twice carefully studied the entire plain of Troy, I now agree wholeheartedly with Calvert’s conviction that the plateau at Hissarlik is the site of the Pergamos of Troy. For one to uncover the palace of Priam and his sons, as well as temples of Athena and Apollo, one would have to remove the entire man-made part of the hill.”

Walls of Troy, Hissarlik, Turkey

Having acquired permission from the Turkish authorities to formally dig at Hissarlik, Schliemann and his team worked feverishly to unearth the ancient citadel from 1870 to 1873, bankrolling the excavations at his own personal expense. His heavy-handed tactics included employing dozens, sometimes hundreds of local laborers, each wielding pickaxes, shovels, and, in some instances, dynamite.

So focused was he on the finding evidence of Homeric Troy and the recovery of precious artifacts that Schliemann literally blasted his way through layers of settlement stratigraphy stretching back to the Early Bronze Age, c. 3000-26000 BC, as well as the remains of the later fortifications – a far cry from the gentle brushing and troweling of today’s archaeologists.

His rough methods soon attracted the ire of professional scholars, especially in his native Germany. Despite that, his speedy publication of excavation reports engaged the wider public, not only placing Schliemann in the media limelight but generating a great deal of popular interest in the ongoing excavations.

The day before excavations were due to end on June 15, 1873, he struck gold. A large cache of gold artifacts, including two diadems, necklaces, earrings, hair-fasteners, pins, and thousands of rings, was discovered in the “burnt layer,” prompting Schliemann to dub the finds “Priam’s Treasure,” drawing a direct line between the archaeology and the historicity of the fall of Troy.

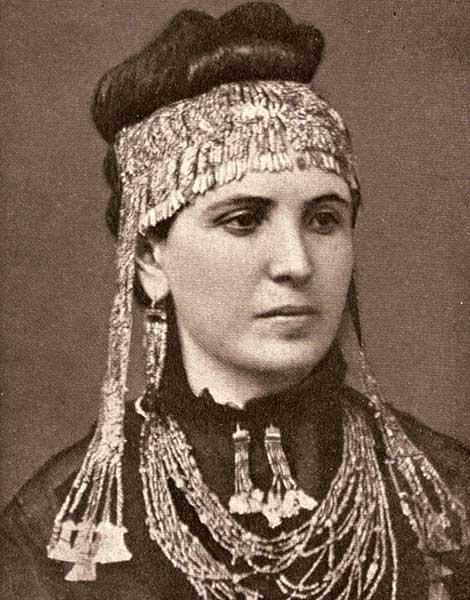

Controversially, Schliemann smuggled the treasure out of Turkey to Greece, famously allowing his Greek wife, Sophia, to wear them in public. A photo from 1874 shows Sophia wearing the elaborate diadem, necklace and earrings, referred to as the “Jewels of Helen.”

Sophia (née Engastromenos), wife of Heinrich Schliemann, wearing treasures discovered at Hissarlik.

The "big" diadem on display in the Pushkin Museum in Moscow.

Following his escapades at Troy, Schliemann proceeded with excavations at Mycenae in the Argolid in February 1874, initially without the requisite permits from the Greek authorities. Abruptly terminated by the local constabulary, Schliemann nevertheless managed to obtain government permission, and excavations resumed two years later under the supervision of the Greek Archaeological Society.

In August 1876, he speedily opened up as many as 20 trenches, employing his now familiar technique of making deep cuts into the fill covering the site, destroying valuable archaeological information in the process.

Schliemann’s unwavering faith in the veracity of the Homeric texts drove his pursuit of the citadel of Agamemnon, the famed commander-in-chief of the Greek forces at Troy. His reliance, too, on the account of the 2nd century AD traveler Pausanias, who wrote that Agamemnon and his courtiers lay buried within the citadel of Mycenae, played a major role in him choosing to dig immediately to the south of the Lion Gate.

Scholars at the time widely believed the early Greeks never buried their dead within citadel walls, so Schliemann was running counter to the prevailing view.

The Lion Gate (c. 1250 BC), the oldest example of monumental sculpture in Europe. Its four massive stones weigh more than 60 tons.

© Mythical Peloponnese

This stroke of genius (or blind stubbornness) paid off. The discovery of six shaft graves in the nearly 28 m-diameter grave circle – “Grave Circle A” – was a watershed in the study of Aegean prehistory. The spectacular finds, published in Mycenae in 1878, included the famous “Mask of Agamemnon,” one of five golden funerary masks found in the circle, the “Gold Cup of Nestor,” and two bronze daggers with inlaid decoration. The singular beauty of these remarkable objects sparked frenzied excitement among the general public, in Greece and abroad.

The now world-famous Schliemann continued working in Greece, notably at the Bronze Age citadels of Tiryns and Orchomenos, where he discovered the fabled Treasury of Minyas, a monumental tomb that bears similarities to the Treasury of Atreus at Mycenae.

With plans afoot to excavate at Knossos on Crete, Schliemann died December 26, 1890 in Naples, Italy, succumbing to an infection which had developed after an ear operation earlier that November in Halle, Germany. He was 68 years old. He was buried in the First Cemetery of Athens in a mausoleum he designed himself along with wife, Sophia (1852-1932), and their daughter, Andromache (1871-1962).

Scale model of Mycenae. Grave Circle A is located to the right after the main entrance.

The golden funerary mask of “Agamemnon,” discovered in Grave Circle A, Mycenae (National Archaeological Museum, Athens).

Schliemann’s investigations in Greece paved the way for the study of Bronze Age Mycenaean society and material culture. The unique works of art which the German pioneer brought to light from the shaft graves at Mycenae vindicated the Homeric epithet “rich in gold,” and inspired others to follow in his footsteps, including Christos Tsountas, who, with James Irving Manatt, wrote the first major synthesis of Mycenaean culture in 1897. As such, many consider Schliemann to be the father of pre-Hellenistic archaeology.

Criticism of his heavy-handed excavation techniques and blind faith in the ancient texts was countered but his rapid (if sometimes unsubstantiated) publication of excavation results. This afforded a platform for scholarly debate which naturally provided an open forum for criticism.

Nevertheless, American archaeologist Carl Blegen (1887-1971), who went on excavate at Troy in the 1930s, noted: “Although there were some regrettable blunders, those criticisms are largely colored by a comparison with modern techniques of digging; but it is only fair to remember that before 1876 very few persons, if anyone, yet really knew how excavations should properly be conducted.”

Schliemann’s Athenian residence, known as Iliou Melathron (“Palace of Ilion”), is now home to the world famous Numismatics Museum of Athens. The three-storey Renaissance Revival/Neoclassical mansion on Panepistimiou Street, built between 1878 and 1880 by German-Greek architect Ernst Ziller, houses a collection of over 500,000 coins, medals, gems, weights, stamps and related artefacts from 1400 BC to modern times.

Heinrich Schliemann (1822–1890), German businessman and early pioneer in the field of archaeology.

© Universitätsbibliothek Heidelberg

Schliemann's grave in the First Cemetery of Athens

Since the time of its founding in the 1880s, the National Archaeological Museum in Athens has been in possession of Schliemann’s finds from his major excavations in Greece. The precious funerary offerings from the royal shaft graves at Mycenae were among the first to be put on display and comprise the nucleus of the Bronze Age Gallery.

The gold death masks and other treasures of the deceased Mycenaean nobility make this collection of unique significance for the history of Mycenaean culture. Schliemann’s finds from the acropolis of Tiryns and a small number of objects from Orchomenos further enrich the prehistoric collections of the museum, providing a hugely popular draw for visitors from Greece and from around the world.

Beneath the busy streets of modern...

From Mycenaean citadels to ancient stadiums,...

From epic battles to avant-garde tragedy,...

How the cargo of a prehistoric...