THE UNSUNG CAPITAL OF MEDITARRANEAN MODERNISM

By Nikos Vatopoulos

In looking at photographs of Athens in World War II, and contemplating which buildings had shaped the city in the 19th century and which had first forayed into modernity after 1910, the ones that stand out most in terms of height and mass are modern. If you could zoom in on the details, you would see that the new buildings which began appearing on the Athens skyline in the 1930s, and a decade after that, represented an architectural vernacular that introduced modernist trends from Central Europe to Athens.

Walking in downtown Athens – particularly along Academias Street, in the streets around Syntagma Square, to the so-called “Neoclassical Trilogy” of the Hansen brothers on Panepistimiou, as well as around Kolonaki – you will see apartment buildings that were once ultra-modern, the latest shout in architectural modernism and residential technology.

Most of these examples of Athenian Bauhaus and Greek Art Deco, despite being around 75-85 years old, are still in good shape. If you follow Academias from its top, near Parliament, pay attention to the building at the first corner of Voukourestiou Street, one of the first truly modern buildings in Athens. From Voukourestiou to Sina, particularly on the odd-numbered side of the street, you will see several facades of the 1930s. One of Kolonaki’s finest examples, built in 1933, is located near the British and German embassies on the corner of Ypsilandou and Ploutarchou. It was designed by a wealthy and well-traveled Greek from Constantinople, Constantinos Kyriakidis, and is one of the most interesting apartment buildings of its kind (note the details). Among all the apartment buildings’ characteristics from that era, the chrome and stylistic motifs of the 1930s exhibit a fascinating variety, making Athens the unsung capital of Mediterranean modernism. Tel Aviv may have the glory, but Athens has all the grace.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

NIKOS VATOPOULOS is a journalist, the author of Facing Athens and creator of the online citizens’ group “Every Saturday in Athens,” which currently boasts more than 24,000 members.

© Katerina Kampiti

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

EUPHROSYNE DOXIADIS is a writer and painter.

“WHERE PERICLES ONCE STOOD…”

By Euphrosyne Doxiadis

The so-called “historical triangle” of Athens is my haunt, including the cemetery of classical times, the Kerameikos, a place named after its potters, who, in antiquity, produced and painted their ceramics for the needs of the city. This area of ancient Athens extending around the Acropolis is where, I feel, the city’s heart beats.

Being one of those people who feels the presence of things that happened in the past and the energy of those long gone, I am inspired and indeed empowered by the amazing aura of this entire area – where I also have the good fortune to live, side by side with the Athens of old.

I have lived on Aeolou Street for 12 blissful years. On weekdays I have a coffee at Magazi or Pera, both on Aeolou just a few steps from my home. I have Hadrian’s Library just a stone’s throw away, and often walk down Adrianou Street to the Theater of Dionysus, where the great dramatists of the 5th century BC competed for prizes with their plays. It is quite something to stand on the spot where Aeschylus, Sophocles and Euripides put themselves to the test 24 centuries ago. The spirit of the place has been enriched forever by their tragedies, endowing the air with the intensity of human suffering. On other days, I walk down Ermou Street until I come to the ancient Cemetery of Kerameikos. I walk near the spot on which Pericles once stood to deliver his renowned Funeral Oration, in honor of those who had died in the first year of of the Peloponnesian War (431-404 BC). This we know from Thucydides’ writings, which still work their magic in present-day Athens, as he himself had hoped when he confided to the reader that he was writing not just for his own, but for all times: “Ες αεί” in ancient Greek.

NEIGHBORHOOD OF DREAMS

By Yannis Zaras

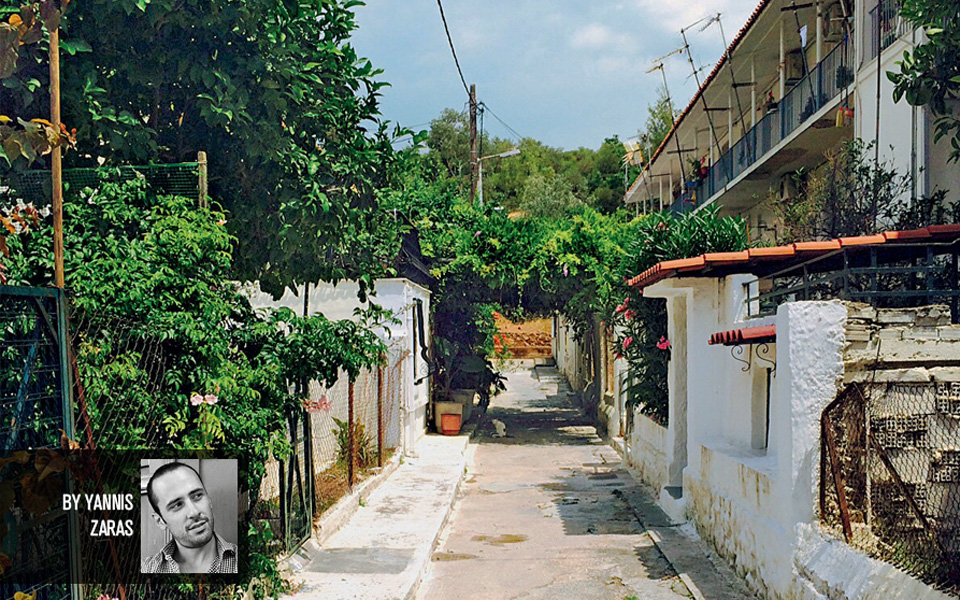

From Thissio, I head up Apostolou Pavlou toward Petralona. By the time I reach the Athinaion Politeia cafe and turn right, the city’s din has ebbed and made way for the serenity of the neoclassical and inter-war-period buildings of Akamantos Street. With my eyes on the Saronic Gulf, I take the Philopappos ring road to reach a tiny district known as Asyrmato (after the WWII wireless station) – once a shantytown for refugees from the 1922 Asia Minor exodus, but improved in the 1950s on the orders of Greece’s Queen Frederica.

In this microcosmic utopia of flourishing post-war Greece, the subject of so many Greek films and songs, which for years had tried to hide in shame, one meets the realism of the present day which no longer has anything to hide. I wander among cats and bougainvilleas, through the fresh herbs and plastic, dismembered dolls of the Kallisthenous street market, past the picturesque Church of Aghia Sotiria. Turning down the side streets of Troodon, past tavernas, meze joints and the Zephyros open-air cinema, I end up, my mind filled with new images, at Mercouri Square, having gotten a sense, in a single afternoon, of life in this neighborhood of toil and dreams.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

YANNIS ZARAS is managing director of Big Olive City Walks.

© Katerina Kampiti

EMBRACING THE UNREMARKABLE

By Dimitris Rigopoulos

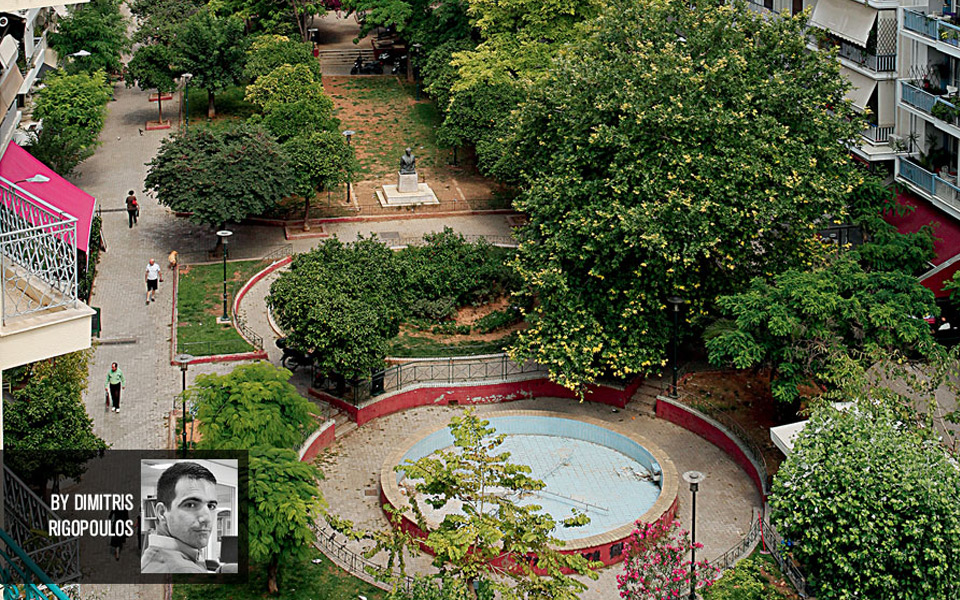

When I welcome guests from abroad to Athens, I think about where I myself like to go when I’m visiting friends in a new, foreign city. Surprise is a welcome element, although I hardly expect to see an elephant in the middle of the road. In fact, quite the opposite, which is why I ask them to show me a slice of “real life,” somewhere tourists don’t normally tread, preferably some “anonymous” neighborhood or part of the city that may be integral to its identity, but which cannot be found in most tourist guides. Likewise, I prefer to show my out-of-town guests unremarkable yet profoundly Athenian parts of my city: the pedestrian area of Fokionos Negri in Kypseli, the main square of Nea Smyrni, or the shops of Glyfada and Kifissia (all conveniently close to a metro, railway or tram station). There is no better way to introduce someone to the local culture than spending a couple of placid hours of observation at busy cafes, bars, shopping centers, etc. They may curse me inwardly for not taking them straight to the Acropolis, but once back home they appreciate having seen an authentic slice of Athens they may never have discovered on their own.

ABOUT THE AUTHOR

DIMITRIS RIGOPOULOS is a journalist.