In the late 19th century, the Frangomahala, a pleasing tangle of streets between the boulevard known as Sabri Pasha and the western city walls, was Thessaloniki’s most sophisticated quarter. Today, it is that once again; its old-world glamor, its once-disused historic spaces and the district’s more recent commercial character have attracted a new generation of creative individuals, and it is once more a choice destination for socializing and culture.

This elegant district above the port takes its name from the term “Frangi,” which refers to the Ottoman Empire’s Latin (rather than Greek Orthodox) Christians. The word “Frangi” came to refer to the city’s prosperous and influential international community, while mahala,” derived from Arabic, was used throughout the Ottoman territories to mean “neighborhood.” The Frangomahala was their commercial and social hub, where they built grand homes, conducted business, worshiped, and went to social clubs. By the turn of the 20th century, the Frangomahala had become a cosmopolitan slice of Europe amid the Ottoman city.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

Thessaloniki’s more European character had already begun to emerge with the arrival of the new Ottoman governor, Sabri Pasha, in 1869. The governor, fresh from his previous posting in Izmir and energized by his successful transformation of that port, embarked on forward-thinking changes that included the removal of the waterfront walls that had closed the city to the sea for centuries. Open to fresh breezes and vistas featuring the Thermaikos Gulf and Mt Olympus, the new promenade soon became prime real estate, filling with cafés and elegant hotels. Streets were widened and modernized, most notably along the Frangomahala’s eastern border. It is now named after the Greek statesman Venizelos, but it was initially named after Sabri Pasha. It connected the Konak – the residence of the Ottoman governor – to a fashionable square on the port. In contrast to the open Oun Kapan Market (today known as the Kapani Market, and still quite lively) to the east, the new shops and department stores along the modern avenue displayed fine imported goods in windows, advertising a more refined shopping experience. Aimed at a cosmopolitan and multilingual community, these European-style shops often bore French names, such as Au Louvre (whose signage indicated ownership by the Fils de Mustafa Ibrahim), and catered to the city elites’ “alafranga,” or Western, tastes in fashion and home decor.

Improvements to the city’s infrastructure supported this more cosmopolitan way of life. As Marc David Baer relates in his 2009 history “The Dönme,” Mayor Hamdi Bey, a businessman from the Dönme community, took office in 1893 with the aim of making “a healthy city, which breathed freely, pulsated with life, and moved towards growth.” His introduction of water and gas companies and a tram company, all partially backed by Belgian interests, were changing the city’s centuries-old ways of life. By the end of the 19th century, the Compagnie des Eaux du Salonique would pipe water directly into the homes of those who could afford it, reducing the importance of the public well as a place to congregate and exchange news. New and more appealing gathering places began to emerge as lighting from the Ottoman Gas Company extended the convivial hours, and new cafés, beer gardens, and elegant hotels started opening up, joined by the Théâtre Français and the Deutsche Klub. These destinations attracted a sophisticated crowd dressed in the latest European fashions, purchased from new department stores such as Stein (whose building, topped by a green glass globe, still stands on the southeastern side of Plateia Eleftherias). For the diplomats, industrialists, and other elite of all faiths, there was also the Cercle de Salonique, a private social club founded by the key names of the day – Allatini, Modiano, Misrachi, Chasseud, Hadzilazaros, and the British consul John E. Blunt.

© Perikles Merakos

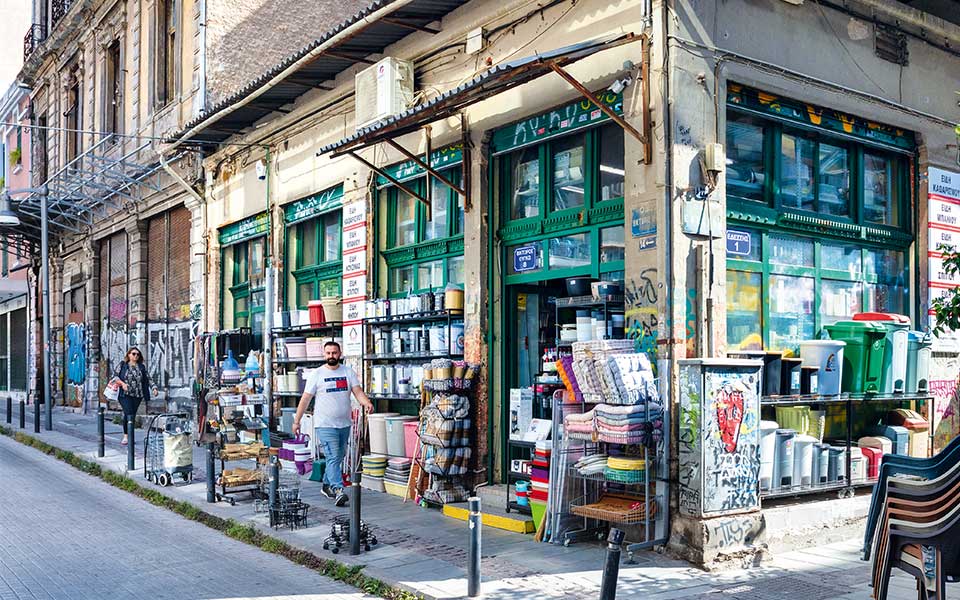

Today, the Frangomahala is again Thessaloniki’s most engaging district, its old-world glamour shining through a pleasingly urban patina created by decades of reinvention. The streets, lined with Belle Epoque buildings and mid-century commercial spaces, are now the setting for round-the-clock activity that’s commercial by day and cultural and social by night. The pre-dawn lull between closing time for Thessaloniki’s best after-hours bars and the start of business for the neighborhood merchants is brief. Mornings here are a whirlwind of activity and aromas – this was and still is a spice merchant’s haven, particularly around the Plateia Emboreiou, the old commercial square – but wholesalers of nuts and dried fruits, and stores specializing in household supplies also abound. Sidewalks are cluttered with blue-and-white patterned feta cheese tins, canning jars, olive oil drums, and glass jeroboams reinforced with basket weave for storing small-batch local wines. Even here in the city, ties to agrarian life and traditional products remain strong. The beautiful Olicatessen (4 Viktoros Ougo) is dedicated to artisanal foods, its shelves brimming with superb products from all over Greece. Around the corner along Frangon – “The Franks’ Street” – there’s more agrarian activity; tomato plants and trays of potted herbs line the shady sidewalks between the music conservatory and Syngrou Street, where you’ll also find Ambelos (24 Frangon), just the place for your wine-making supplies.

Another block to the west on Frangon brings us to Neon (14 Leontos Sofou & Frangon). This is one of the few bougatsa (a local pastry) stores that still stretches its own filo dough by hand; it’s the perfect place to try the famous “sketo” – just plain crispy flaky dough with no filling. Across the street, you’ll see the State Conservatory housed in a 19th-century mansion. Its neoclassical and baroque details beneath a mansard roof reflect the district’s international identity, while the story of the building demonstrates Thessaloniki’s transition to modernity in the nineteenth century. The mansion was originally the Thessaloniki home of the Abbotts. Jackie Abbott, a rather notorious businessman, made his fortune through a monopoly in the supply of leeches, which were popular in the healthcare industry then. It was a symbolically significant beginning; he would soon amass a greater fortune by transitioning into money-lending at exorbitant rates.

© Perikles Merakos

© Perikles Merakos

The mansion on Frangon Street wasn’t the main Abbott family home – their principal estate stood just outside of town. Abbott planned to host Sultan Abdulmecid I there during his 1859 visit. In his 2004 volume “Salonica, City of Ghosts,” Mark Mazower relates details of astonishing excess: Abbott had a 10-kilometer road leading to his estate covered with carpets for the Sultan’s approach.

Fate, however, didn’t smile on this ostentation; a thunderclap just as the Sultan was about to descend from the carriage is said to have put him off his visit, and not even coffee, brewed carriage-side with Abbott himself allegedly stoking the fire with banknotes, could induce the Sultan to stay.

In any case, the sun was rapidly setting on private money-lenders like Abbott; only a few years after the Sultan’s visit, the Abbott mansion became the headquarters of the Imperial Ottoman Bank. The path to international capitalism was not welcomed by all; in April of 1903, the “Boatmen of Thessaloniki,” whose stated intent was to “…sail towards freedom and the wild seas beyond the law,” set off a series of explosions, the last of which destroyed all but the Ottoman Bank’s exterior walls. The bank was rebuilt. Today, behind the wrought-iron fence, serenaded by the music wafting through the conservatory’s tall windows, stands the slightly damaged statue of a seated woman, a relic of the lost world of the Abbotts and the only trace of the bombing incident.

© Perikles Merakos

Located east of the conservatory stands the Holy Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception (19 Frangon), a stunning example of neo-Renaissance architecture constructed by Vitaliano Poselli for the Catholic community in the late 1800s. A prominent architect of the city’s Belle Epoque cityscape, he also designed the new headquarters of the Banque de Salonique – built within the garden of the old Allatini mansion. Today, it is a shopping arcade called the Stoa Malakopi, notable for its ornate neo-baroque facade and for a clock that still shows the exact time of a 1978 earthquake. On a warm night, much of the neighborhood’s energy converges here, around the fountain and benches at the end of a broad pedestrianized stretch of Syngrou that’s ideal for socializing. Along the northwestern side of the stoa, the minimalist spaces of Arcade (2 Vilara), with coffee by day and cocktails and music by night, still convey an air of old-world elegance. This section of Stoa Malakopi opens onto Katholikon (“Street of the Catholics”), where you’ll find Giapi (1 Katholikon), the after-hours spot of the moment thanks to its quality drinks and music selection that ranges from experimental electronic to ’60s garage.

La Doze (1 Vilara) is located directly across from Stoa Malakopi and is known for its lively crowds and pool table. At Toss Gallery upstairs, exhibitions and events include interactive, collaborative, and experimental projects, comic art, 3D projections, and screenings of independent films. Another notable contemporary art gallery is in the historic De Mayo building, on an alley to the east. The Eye Altering (2 Paikou) fosters emerging artists. On your way there, you’ll pass by Beetroot. Here, an established team of graphic artists has developed a signature style that’s minimalist, expressive, and playful. The energy is contagious at their airy café-bar and shop, an ideal spot whether working on your laptop or enjoying a glass of wine. Artpeckers (12 Valaoritou) focuses on still more unique local graphics. The geometric motifs and patterns on their bags, accessories, and homewares, all made in collaboration with Greek suppliers, are inspired by Greek culture and mythology.

Katouni, the commercial lane connecting Vasileos Irakleiou and the Plateia Emboreiou, offers two very different, albeit both traditional, pleasures to round out your wanderings. Orfeas (35-39 Katouni) has been making traditional sweets such as “glyko tou koutaliou” (preserves) for three generations. Their caramelized “Halva Farsalon,” made in traditional hammered copper vessels in the back of the shop, is particularly delicious. If you have a tad more time to spare, stop by Harara Hammam (33 Katouni) for an authentic hammam experience that includes a massage; it’s a fantastic way to revisit centuries of Ottoman bath culture. You’ll be relaxed, glowing, and ready for more exploring or a night out after some tea in the adorable hidden courtyard.

© Perikles Merakos

Vitaliano Poselli

As Ottoman Thessaloniki adopted a more European character, Vitaliano Poselli became one of its key architects. His iconic works, both public and private commissions, helped shape the city’s Belle Epoque period. Mayor Hamdi Bey commissioned Poselli to design significant public buildings, including the new Konak, or Governor’s House (1894), and the Military Headquarters (1903). Poselli’s private commissions were more expressive.

Eclectism was the style of the moment, and Poselli, fluent in the stylistic vocabulary of a host of historical periods and in the ArtNouveau of the era, handled it with grace. His commercial landmarks are the Banque de Salonique and the Allatini Mills. In addition to the Cathedral of the Immaculate Conception in the Frangomahala, he also designed several other houses of worship, including the Armenian Church (4 Dialetti), the Beth Saul Synagogue (destroyed in 1943), and the Geni Tzami (built for the Dönme community and still standing). Poselli also designed the Villa Morpurgo and the Villa Allatini.