Ancient Pollution: How Greece’s Past Speaks to Our...

Think environmental pollution is a modern...

The 3-D mapping and reconstruction of valuable objects, monuments and historical areas – such as the old town of Xanthi – are at the heart of ILSP’s work.

by: Tasoula Karaiskaki

Τhe Athena Research Center’s Institute for Language and Speech Processing (ILSP) serves a vital role in the maintenance, analysis, study, promotion and dissemination of our great cultural heritage – in no small part through the use of technology. This includes the digitization of rare archives and artifacts, the 3-D mapping of valuable objects, monuments and historic regions, the digital recreation of real and fictitious worlds and virtual tours through exhibitions and museums.

Now, a new goal is emerging from the lockdown and travel ban imposed by the coronavirus pandemic: to bring Greek culture, in all its complex glory, straight into our homes.

If you’d like to see a 5th-century BC “lekythos” (a type of ancient Greek vase used to store oil) from Attica, you can now call one up on your screen. Not only that, you can also rotate it, turn it upside down and scrutinize its every detail. You can see it in the exact spot it was found, and even take a “walk” around the excavation site of Abdera or “fly” over it to observe the whole region from above.

If you want to examine the ancient object known both as the “Dancers of Delphi” and “Acanthus Column,” you can make it spin around on your screen, you can delve into the acanthus leaves, and even admire the pleats on the dancers’ dresses, down to their last detail.

Cup (Kylix) - Archaeological Museum of Abdera

© Europeana

If you would prefer to visit the Rotunda in Thessaloniki, you can approach it from on high, examining its roof before stepping inside the building to look at the Eastern and Western alcoves, and the mosaics on the arch frames and the large dome. You can even wander around outside.

Or perhaps you’d rather browse through gospel lectionaries from the Komnenos dynasty of the Byzantine Empire, decorated with sophisticated miniature drawings, or the illuminated manuscript “Codex 5” (recounting the “Romance of Alexander the Great”), all kept at the Hellenic Institute for Byzantine and Post-Byzantine Studies in Venice.

Thanks to the efforts of the ILSP team, who traveled to Venice with huge flatbed scanners and other special equipment to digitize these normally inaccessible treasures, you can now see them on your screens and go through them page by page – something that even scholars could not do until recently.

According to Vassilis Katsouros, the director of the ILSP, “We provide tools that enable users to navigate through the electronic treasures that ILSP has created. They can search for precise audiovisual information in videos, identify and analyze historic manuscripts or polytonic texts, and even translate Byzantine texts or ancient manuscripts into modern Greek. They can create digital material for teaching old dances, or identify music pieces with particular characteristics (for example, all those pieces that have the same rhythm or melody), or convert audio files into sheet music, or even ‘see’ the ingredients that make up a certain meal.”

Rotunda, Spolium

© Europeana

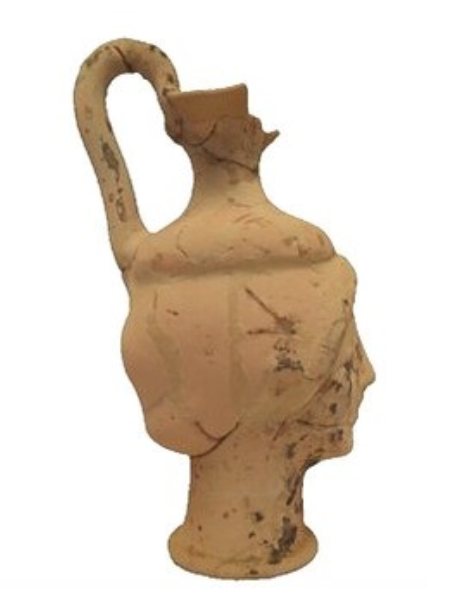

Head-Vase (Oinochoe), Archaeological Museum of Abdera

© Europeana

Katsouros continues: “The Cultural and Educational Technology Institute (CETI) was founded in Thrace in 1998 and became a part of the Athena Research Center, one of the first centers to develop digital archaeology, using a holistic and multidisciplinary approach to the conservation and promotion of objects and monuments. Workshops were created, both for material analysis using physico-chemical methods and for 3-D digital mapping, restoration and reconstruction of objects, monuments, and historic areas. We use cutting-edge technology on the ground and in the air (drones) that identifies the 3-D characteristics of the object, monument or area and creates precise 3-D representations.

“Furthermore, thanks to new image-processing techniques, we are creating digital collections, 3-D museums and virtual exhibitions displaying items that exist in real museums. Additionally, we recently participated in an important European project which features a different approach to the presentation of exhibit items, revealing each one through digital dramatized narratives built around plot lines, with characters reliving past events.”

Research director Nestor Tsirliganis describes the technologies used by the branch of the ILSP in Xanthi, which he heads: “To date non-organic findings like ceramics, we use methods such as thermoluminescence and optically stimulated luminescence. An item’s provenance is determined by analyzing the clay and comparing it with the composition of the soil in the ancient clay-producing areas – Northern Greece, Attica, the Corinth area and others.”

There has been a slew of chronological dating studies on items found in digs all around Greece. The most impressive one is the dating of the great eruption of the Santorini Volcano, carried out by the branch’s Department of Archaeometry, led by Tsirliganis himself.

As he explains: “We dated samples from the deepest point (a depth of 5000m) of the Mediterranean seabed off the coast of Pylos, and found when the volcano had erupted – 1613 or 1614 BC.”

Thermoluminescence, Tsirliganis explains, “establishes the last time a material was heated to a high temperature, and optically stimulated luminescence allows you to estimate the last time a material was exposed to the sun. At a certain layer of the seabed, both chronologies coincided. The material had escaped the magma at an extremely high temperature and had then fallen into the sea. It was precipitated and never exposed to the sun again.

“Such calculations contribute to our knowledge of the past. For example, analyzing the material content of different utensils teaches us a lot about nutrition and social habits at a certain time.”

The institution known as CETI in Thrace, which became a part of the Athena Research Center, played an important role in the development of digital archaeology.

Each exhibit is augmented by digitally dramatized narratives built around a plot and characters.

Tsirliganis notes that the Institute also has virtual workshops available. “Different measures and analyses have been simulated either for educational purposes or to enable handling of the laboratory equipment from a distance; researchers can upload their samples into a system to carry out measurements remotely.

“Other digital tools help with archaeological studies: they locate the positions of settlements or rivers, and they map different territories. For example, the study of a sanctuary and its surrounding observatories allowed us to digitally draw a path, which was later discovered at the exact same location during an excavation. Our team was the first in Europe to upload three-dimensional digital reconstructions of objects and monuments onto Europeana, the European cultural database.”

The “Clepsydra” Cultural Heritage Digitization Lab and the Multimedia Research Lab teams create 3-D digital representations, virtual exhibitions and museums, interactive 3-D narratives, databases, cultural and educational portals using multispectral cameras, scanners, digitization units and others.

“We duplicate originals so that, should they ever get destroyed, at least their digital copies will be saved forever,” research director and head of the Multimedia Research Lab Giorgos Pavlidis explains.

“Using that material as a base,” Pavlidis continues, “we build applications for experts, archaeologists, museologists, anthropologists and teachers, as well as tourism professionals and creative industries in search of innovation. Afterwards, we close the loop with 3-D printing, we return the items to the real world and we go back to where we started, producing – on any scale desired – replicas of the objects or monuments that we’ve brought into the digital world.

“We’re currently working on research projects that include the social integration of people with disabilities into cultural activities; supporting local economies by increasing innovation in cultural activities and tourism; automated aerial 3-D mapping of large cultural heritage sites such as entire urban areas; and applying machine-learning techniques for inductive learning.”

Archaeologist, research director and head of ILSP’s Department of Culture and Creative Industries Despina Tsiafakis describes the wide use of digital media in helping to discover, study and present the past:

“As a research entity, not only do we make use of digital tools ourselves in research and in our programs, we also train young archaeologists to use them. These tools are varied, and they’re used for everything from site localization, research and excavation, registration and study of material residues, right up to publication and promotion.”

“With the help of remote sensing, geoprospecting, Geographic Information Systems (GIS), digitization, databases and digital repositories, 3-D visualization, augmented reality, virtual environments, virtual tours and, last but not least, the internet,” Tsiafakis says, “what first seemed like random pieces of stone, brick and ceramic takes on new shape and meaning and becomes a monument, a building, or even an entire site. When a broken piece of pottery (ostracon) is returned to its original form, we can understand its shape and its use.”

“Digital technology” Tsiafakis adds, “is of great assistance for saving time during procedures and material management, as well as for reversibility: The digital completion or reconstruction of a building, sculpture or vase allows us to ‘rebuild’ it if we uncover new data that contradicts the restoration, while the real cultural item remains intact. Furthermore, digital technology helps expand cooperation and multidisciplinarity. It carries cultural information that reaches everyone everywhere at the same time.”

Think environmental pollution is a modern...

Discoveries along Amalias Avenue, from the...

A 3D reconstruction by Oxford researcher...

From Crete to Olympus, hike the...