The Armata Festival and the Allure of Spetses...

Experience Spetses in its most enchanting...

Three generations of Karpathian women outside the famous Folia taverna.

© Nicholas Mastoras

Βefore the days of email and text messages, when we still sent cards and letters in stamped envelopes, we would write, under the particular island and postcode (e.g. Kos 85300, for those of us who hail from that island), 12-nese, an abbreviation of dodeka (12) and nisos (island). We are Dodecanesians, living in the 12-isles. Closely affiliated, after a fashion, with that number: twelve noon, twelve midnight, the Twelve Gospels, the Apostles, the months. After 3, 7 and 9, twelve is the next magic number in the sequence.

Except for one thing: there are not exactly twelve. There are several more; fifteen main islands and 93 islets, 27 of which were inhabited as of 2006. From Patmos to Kastellorizo, the ferry boat usually takes as many hours as it does for the route from Athens to Patmos; in other words, not only do our islands number more than twelve, they are also scattered across a sizeable area on the southeast fringes of the Aegean. So perhaps the geographical term Southern Sporades, the older appellation of this island complex, would better describe our region.

Large crowds attended the ceremony marking the annexation of the Dodecanese islands into the Greek State, March 7th, 1948.

© Antonis Pachos, from the book "Rhodes-One Hundrend Years of Photography 1850-1950”, Simeon Dontas

Moreover, “Southern” suggests “Northern,” and “Eastern” and “Western,” too, for that matter. The geographical definition in itself highlights the unity of this island region with the rest of the Aegean. Those of our grandparents who, born at the start of the 20th century, spent their childhood under the Ottomans, and their adolescence and adulthood under the Italians, the Germans and the British, were driven to fight for unification with the rest of Greece by this strong awareness of an organic unity. Ethnologically and culturally, in the wider sense, the island world of the Aegean is irrefutably undivided.

It is, however, subdivided into distinct regions: the islands of the Northern and Eastern Aegean; Evia; the Sporades; the Cyclades; Crete; the Dodecanese. The boundaries of these districts are obscured due to the interrelatedness of the islands: is there a difference, for instance, between Patmos and Samos, or Astypalea and Amorgos, or Karpathos and Kasos and Crete? The thought has often crossed my mind that if I were to be led blindfolded through lanes and neighborhoods unknown to me, not just on Kos but also on Patmos, Leros, Kalymnos, Nisyros, Symi, Tilos, Halki and Rhodes, or anywhere else in the region for that matter, and I was then asked, eyes uncovered, to say where I was, some kind of intuitive sense of place would prompt me to reply: “I don’t know exactly where, but I know I am in the Dodecanese.” But having said that, our islands are quite distinct from one another.

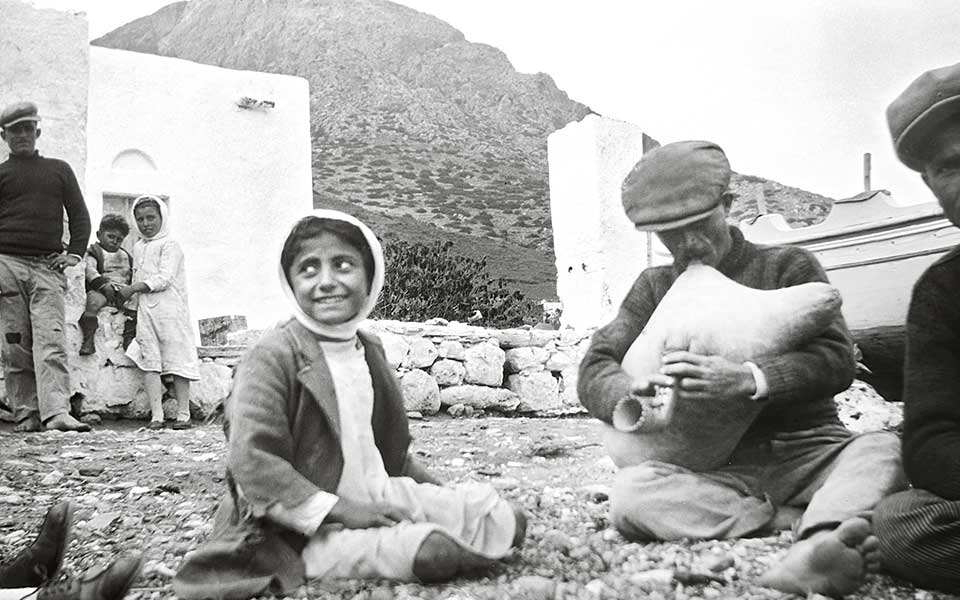

Playing the bagpipe on a beach. Kalymnos, circa 1935, Elli Papadimitriou.

© Elli Papadimitriou, Benaki Museum / Photographic Archives, Simeon Dontas

Α boy from the village of Menetes, Karpathos, sets off for an afternoon soccer game.

© Nicholas Mastoras

It may be that this intuitive sense is evoked by the light, that is to say by the geographical coordinates of the region, or perhaps by the proximity of our islands to southeast Asia Minor (i.e., to ancient Caria and Lycia). Or maybe it is evoked by the particular historical, Mediterranean adventure of this offshoot of Hellenism: the roughly two centuries when the Dodecanese was under the rule of the Knights of St John (ca. 1306-1522), the chivalric order that came from the Middle East before eventually settling in Malta. Or perhaps by the more recent three decades of Italian occupation (1912-1943), a defining period for several reasons, whose influence is still evident on the islands today. Or even by the pervading cosmopolitan character, as much in the architecture as in the way of life of the towns and smaller communities of our islands.

And yet, all of the above may well come across as idiosyncratic projections, similar somehow to the way that, riven by emotion and with great poetic license, we invent different reasons when asked why we love our homeland. The most honest answer is, of course, the word “affinity.” I love my homeland because, of all other places, it is the one with which I feel the closest affinity.

Celebrating the Dormition of the Virgin Mary on Kasos.

© Julia Klimi

I remember observing how, on my mother’s side of the family (they came from the urban middle class of Kos Town), grandmothers, aunts and female cousins would set the table and serve meals following an etiquette that differed from the traditional French form that other middle-class Greeks adopted. I would later find the same conventions in Hora, the main town of Patmos, as well as in corresponding circles on Rhodes, but also in a book about the cuisine and middle-class practices of Smyrna.

There also seems to be a particular Dodecanesian character in the working-class neighborhoods of our islands, such as in the port town of Skala on Patmos, in parts of Kalymnos, in the Halouvazia neighborhood of Kos and in the lanes of the Old Town of Rhodes. For all their diversity due to their geographical fragmentation, the local Dodecanesian vernaculars (as I learned studying linguistics) are classified under the southeast island idiom, together with those of eastern Crete and Cyprus.

The kafeneio, then and now: Top: Kos, 1955. Bottom: Karpathos 2018.

© Getty Images/Ideal Image

© Nicholas Mastoras

To an islander, islands are never pieces of land surrounded and cut off by the sea; on the contrary, they are floating worlds in constant motion. On this watery planet, every island group is also a fleet. This is especially true for our own isles, a tiny fleet on the southeast fringes of the Aegean on a course that has always been Greek, yet, on account of its history, a fleet that is also eminently cosmopolitan, which is why it is ideally suited to the particular kind of economy afforded by tourism.

In 1989, after my studies and military service, when I decided to settle on Kos, and return permanently to the place where I had lived until my adolescence, I planned, then, among my many other youthful schemes, that if I ever had a whole year to spare, I would spend one month on each island in the Dodecanese and write a short story about each, with just the names of the particular islands as headings. The entire collection was to be titled “Dodecanese” or simply “Twelve.” In the meantime, and since life itself proves much more thrilling than our plans, I got involved in other things; and besides, the Dodecanese are not just twelve (nor would be the months that I would have to allot to the project)… so, for now, the “South Sporadiot” has largely outflanked the Dodecanesian within me.

Boys dressed as revolutionary war soldiers for a National Day performance on Rhodes.

© From the book "Rhodes-One Hundrend Years of Photography 1850-1950”

Members of the Lyceum of Greek Women Traditional Dance Troupe in Kardamena, Kos.

© Clairy Moustafellou

But then again, one should definitely not rule out what might come to pass over the years; perhaps at some time in the future I will tear through every vessel in our fleet down here; the months of the journey will of course be more than twelve, and the title of the short story collection will be Southern Sporades rather than Dodecanese. Until such time, my innermost distillation regarding a homeland (namely Kos, although I think that it also applies by extension to the totality of our islands) has already been recorded in my short story, “Daniel Goes to Sea” – below is the relevant excerpt:

“There is something about the Near East, I sometimes think, perhaps it’s the fatigue following the millennia of living in the same spot, of places and cities that remain the same, sometimes prosperous, sometimes in decline; there is something here that is unbearably fed up with what is superfluous, that attributes the highest aesthetic value to anything that safeguards the minimally essential. See to it that anything you make becomes exactly as much as you need it to be. Little or great as it may have need. Then it will also be incontestably beautiful. This is what beauty is over here.”

Experience Spetses in its most enchanting...

More and more Europeans retire to...

While some historic buildings teeter on...

Discover festivals, beaches, food, and hidden...